CommWealth is Published

Dystopian? Black comedy? Literary? Mainstream, contemporary–what on earth do those terms really mean? CommWealth has been published by Class Act Books. Describing a society in which all forms of property have been banned so that a deeper sharing can take place between citizens, CommWealth isn’t science fiction but is just as bizarre.

Dystopian? Black comedy? Literary? Mainstream, contemporary–what on earth do those terms really mean? CommWealth has been published by Class Act Books. Describing a society in which all forms of property have been banned so that a deeper sharing can take place between citizens, CommWealth isn’t science fiction but is just as bizarre.

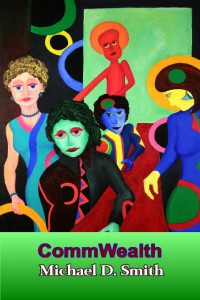

The novel is available from Class Act Books in paperback and in EPUB, MobiPocket (Kindle), and PDF eBook formats. It’s also available from Amazon as a Kindle eBook and in paperback. The cover features one of my paintings of the characters, Property, or The Cup of Fog. More background can be found on my CommWealth web page.

Introduced six months ago, the CommWealth system has outlawed private property. Playwright Allan Larson has adjusted well to this new society, easily claiming umbrellas, mansions, and Porsches from fellow citizens. Any object from your house to the clothes you’re wearing can be demanded by anyone, to be enjoyed for thirty days before anyone else can request it.

Still obsessed with his ex-girlfriend Lisa, Allan invokes the laws of CommWealth to demand ownership of her. When bicycle mechanic and fledgling actor Richard Stapke discloses that he’s secretly been writing novels and plays for years, Allan incautiously spreads the word that Richard’s a genius, with the result that an official CommWealth claim is made of Richard’s entire literary output. The resulting five-volume Stapke Intimacies brings to light a twisted history of betrayals, double agents, and murder that propel members of the Forensic Squad theatrical troupe into a suicidal revolution.

In this excerpt, CommWealth Inspector Jonathan Hardy investigates a possible Hoarding charge against bicycle mechanic Richard Stapke:

“Mr. Stapke,” Hardy said, tapping something ominous into his laptop, “let’s assume that your entire last statement was hypothetical. In that hypothetical case, in which you are a mere bicycle mechanic, of course you owe no Writer’s Tax. But, since you do have writing, and since you are a writer, you owe seventeen percent.”

Richard opened his mouth and shut it. “Seventeen percent? Hypothetically speaking, seventeen percent of what?”

“Of your output, of course. Let’s say you produce two hundred pages per month, maybe fifty-thousand words, as you do seem quite prolific. Of that, seventeen percent, or thirty-four pages, or eighty-five hundred words, would be sent to the CommWealth Central Tax Assessor’s Office.”

“What?” Richard and Allan both cried.

“If you produce more than say, five hundred pages a month—if you’re a real barn burner, that is, it goes up to fifty percent. So, of course, it’s best to stay around two to three hundred. We know that nobody wants to lose half his writing.”

“What?” Richard repeated. “You send—actual writing—to…to…”

“To the CCTA’s Office. On the last day of the month you simply upload your entire month’s output to the CCTA web site, which in turn sends it to the CommWealth Cultural Redistribution Office. That office determines the seventeen percent tax and distributes it to needy writers all over the country, then refunds the remaining eighty-three percent back to you.”

“My—God!”

“You see, there are many unfortunate writers who would like to be able to create, but who are, for some reason or another, blocked from doing so. It’s a most distressful situation. I’m sure you can relate to that, Mr. Stapke. You know how difficult it is to produce great writing, and how easily it is to get blocked or sidetracked.”

Richard frowned. “No, I don’t know that.”

Hardy cleared his throat. “It hardly needs to be stated that there are vast quantities of unpublished material in this country that are hidden away. People tend to Hoard their writing like dark secrets. Well, what we’re doing with the Writer’s Tax Program is to bring those dark secrets out into the open, and get them into the hands of needy writers who can then have them published under their own names.”

“I don’t believe this! Are you saying this only applies to unpublished material?”

“Of course—although anything a writer produces on a given day is by definition unpublished. It doesn’t even matter if a writer has a contract to write that particular work—it’s still considered taxable by the CCTA. As soon as it’s produced, seventeen percent—or whatever the percentage comes out to be—is ours. And, I should add, you must surrender all your copies of those taxable pages for CCTA inspection—paper, CD, flash drive, or whatever—because they officially cease to be yours in any way.”

Richard shook his head. “Forget it…forget it…”

“And it has to be the best seventeen percent of your writing—no low quality toss-offs and then shuffling that to the CCTA. The Cultural Redistribution Office uses the CommLit program, which has all sorts of fascinating algorithms for comparing the quality of different sections of your writing—and it always gets your best seventeen percent.”

Copyright 2015 by Michael D. Smith

Pingback:Fannin and Felicia: Wasn’t Art Enough Passion? – Sortmind Blog – Michael D. Smith