Is Abstract Art More Difficult?

Why does abstract art seem more difficult to me than does representational art? Abstract would seem to be play, and sometimes in fact it’s easy play. But the easy gifts are just that, gifts. The gifts are welcome to an artist, and often the clearest channel to the Source, but they come … when they feel like it.

Most of my abstract art has been necessary and difficult. So difficult that I often wonder, especially after the exhaustion of a painting, why I bother to do it. But it’s the necessity that pushes the painting out. Although my need for writing is greater than my painting need, writing is such a different process that I can’t compare it to painting at all.

“Difficult” can signal “on the wrong track,” of course. A poor tuning to the Source, poor channeling, distraction, tiredness, can frequently lead to the place where the initial free play eventually morphs into the inevitable “problem.” “Getting into trouble” is a phrase I often find myself using as I slide towards this state.

Why is abstract more difficult, then? Is it just a matter of too many variables to control?

- colors

- shapes

- transparency/opaqueness

- textures

- amounts of paint required

- forms of meaning

- forms of listlessness

- composition, aesthetics

- passion

- energy

- chemical nature of paint

- expected reactions/results

- unexpected reactions/results

There’s an obvious comparison to music, especially instrumental music, in that the paint, and the musical notes, don’t refer to anything in the outer world, and the endless variables must be combined to open a channel of meaning and passion without reference to that outer world. If this effort fails, the result is dull singsong, clever little patterns, no divine energy.

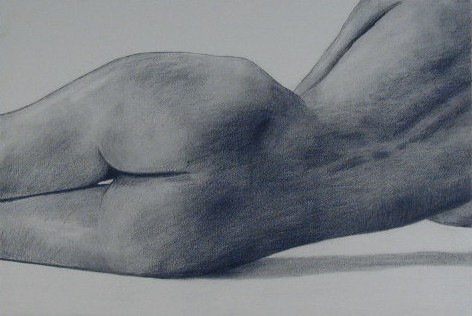

There’s another factor from the audience’s point of view: showcasing your credentials and expertise as an artist by producing an acceptably realistic work. I happen to enjoy an occasional realistic drawing, but I’m probably not alone in wanting to display on my web site some examples of realistic talent, such as this one, which I based on a photo in an anatomy book.

Note that we probably wouldn’t be very interested in a similarly realistic drawing by Chagall, perhaps from his student days, except perhaps as “proof” that there was some sane underpinning to his later fantasy works.

However, I have to say that the above drawing, while it took several hours, was easy to plan and execute. I look back on it without any memory of struggle or excessive energy expenditure. But when I look back at this six foot by four foot painting,

I can recall, not without some pangs, all the “getting onto trouble” inherent in pushing it out. I remember the tremendous effort to stabilize it, to hammer away until a sense of my own channel emerged.

Is a difference apparent between the above abstract and the following one, which more or less poured out without a struggle?

Or between those and one like this, somewhere between easy and a struggle?

Here is a huge piece, five feet by fifteen feet, that I thought out in advance and executed according to a plan. Though it took several days, it was never a struggle:

So it may be hard to tell from the outside which abstract painting was a struggle and a revelation and which was in essence a fairly easy summing up of lessons already learned beforehand.

I usually want to complete an abstract painting in one day, in a single rush of energy and contact. However, I recognize the arbitrariness of that time limit, and I also realize that pushing it like that can result in late night exhaustion and inability to make creative decisions, thus making it even more difficult to solve problems.

“Problem solving” is an issue of its own. How did you get to the place where these problems arose? Was the problem inevitable, a necessary part of the process, or was it due to the fact that you were unprepared? Perhaps you sought easy play and were shocked when buried forces arose to mock your superficiality.

It may sound farfetched, but there have been many paintings during which I’ve felt something akin to “fighting for my life.” Sometimes it’s chagrin at the problem and the struggles necessary to solve it, sometimes it’s more that the passion itself is there, but just not coming through.

I know when a work is done. I know when to end it. Even if I make a mistake and declare a painting finished too early, I inevitably realize that and go back and deal with it. If the resulting finished work is not as exciting to a viewer as a realistic piece, so be it. Realism is beautiful and we can all admire the talent of execution, and of course it can embody the same meaning and passion found in a good abstract.

But in any realistic work I’ve done, though I may have been exhausted by it, run into problems, grappled with meaning, or forgot to clear the channels to the Source, I’ve always had the comfort of the safety net of craftsmanship beneath me. I could plan and execute the work knowing there were rules to follow, forms to copy, lines to adhere to, methods that others had used and which I could use as well.

There is no safety net in abstraction. Everything is up for grabs. The only safety is the relentless urge towards meaning and passion.

You can try to create a false sense of safety, of course: the safety net of faking it. “Artists” have done that for centuries in a variety of ways, both realistic and abstract. Much of abstract art is in fact a put-on, a scheme, dishonest, “easy,” but it may pay enough to get an “artist” through another scary day.

Having that said, I recognize that we all must deal with delusion, being on the wrong track, fooling ourselves. It’s just that abstract art magnifies those risks.

copyright 2010 Michael D. Smith

Pingback:Arboreal Ghosts / Last Stop This Route | Sortmind Blog

Pingback:Arboreal Ghosts / Last Stop This Route – Sortmind Blog – Michael D. Smith

Pingback:The Blog Evolving into the Entire Journey – Sortmind Blog – Michael D. Smith