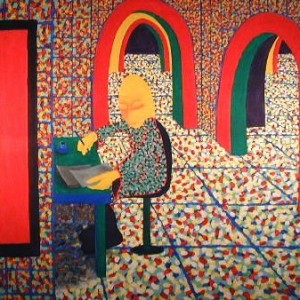

Why should I post a play I wrote at the end of my freshman year at Rice? Because it does seem timeless to me. It seems like one of those wise childhood things we sometimes write and then forget for decades how to do. It’s also has fun and zany archetypes, it was performed three times in 1972 and once in 1973, I DID play the War Correspondent, AND I now have an opportunity to format the play according to standard guidelines, just to get a feel for how it’s done. It was educational to format my Word document to include the proper tab stops for stage, scene, and character stage directions, but for the purposes of the blog I’ve just centered or indented them as looks best.

Why should I post a play I wrote at the end of my freshman year at Rice? Because it does seem timeless to me. It seems like one of those wise childhood things we sometimes write and then forget for decades how to do. It’s also has fun and zany archetypes, it was performed three times in 1972 and once in 1973, I DID play the War Correspondent, AND I now have an opportunity to format the play according to standard guidelines, just to get a feel for how it’s done. It was educational to format my Word document to include the proper tab stops for stage, scene, and character stage directions, but for the purposes of the blog I’ve just centered or indented them as looks best.

This post is another homage to past influences: believe it or not, the revelation of how Dostoyevsky used dialog in The Brothers Karamazov, which I first read in Spring 1971. Several people have remarked, and I agree with them, that one of my strengths as a writer is dialog. Especially the kind where people are saying absolutely crazy, emotionally off-the-wall things to each other, like Fyodor to Father Zossima.

So it often seems natural for me to go one step further in a novel and have a chapter be a recording, often secretly made by one villain or another, in which I can just have the characters function as actors. No descriptions of long regal noses or who brought whose coffee cup to whose lips, just raw dialog. That’s not a real play; in fact, I once attempted to rewrite a novel as a play and it failed horribly. So I’ve been content with occasional dialog scenes. To effect a suitably dramatic ending to the secret recording, often where I can cut a character off in mid-sentence, I often resort to technological disasters such as: “Hey! Don’t step on the tape re–” or “Watch out, idiot, you spilled your drink right on the tape re–”

TOTAL ANNIHILATION: CAMOUFLAGE!

CHARACTERS

ISAAC: high school philosopher

JERRY: high school jock

BRENDA: high school cheerleader

MARY: high school poetess

WAR CORRESPONDENT

PROLOGUE

(A stretch of devastated dirt. Smashed pasture fence. A few bullet-riddled German army helmets, strewn randomly. A skull. Dead and rotting blackbirds. Some gray stones. Fog, smoke, the smell of gunpowder. Ominous yellow light in the background. Somber silence.)

(Enter WAR CORRESPONDENT, a typical World War II U.S. battlefront war correspondent, helmeted, dirty khaki uniform, bearded, exhausted. Carries pencil and notebook.)

WAR CORRESPONDENT

(voice taut with anguish and exhaustion)

This … this is all that’s left … you people on the sidelines, safe back on the mainland, you people didn’t get involved in it. In this terrible war. You didn’t understand … you didn’t …

(gropes for words)

You–you sat at home on soft couches, you read magazines, went to parties … but … while over here, this happened …

(pause)

I’ve covered this war since it began. I’ve seen the hell and misery, the glory, the heroism, and the senseless death of it all. I’ve touched this war with my own hands … I’ve …

(chokes)

And now you’ll see it as it really happened …

(looks through his tattered little notebook; philosophical)

Let me tell you that war doesn’t begin with the first killing–it’s born in the hearts of men from the day their Maker endows them with the breath of life, from the day of their birth which the Devil corrupts mightily and here ever after fire and brimstone almighty. September first, August fourteenth, Berlin, Paris, Washington, Tokyo–dates and places do not matter. It’s the evil born into men that starts wars! And so this little history I’m about to give you shows the senseless, hateful, Devil-inspired evil … the evil of … man …

(pause)

It all began on April 15, six years ago, in a little smoke-filled nightclub in Paris …

(Voice trails off, lights dim, curtain falls slowly.)

ACT ONE

(A Jumbo Burger joint at night. A counter and four tables. At table second from left two teen-aged American guys, ISAAC and JERRY. At table on far right, two teen-aged American girls, BRENDA and MARY. All four well-dressed and beautiful. WAR CORRESPONDENT behind counter silently taking notes.)

GUYS’ TABLE

(Munching hamburgers; JERRY wearing high school letter sweater; ISAAC wearing black Hamlet costume)

Yeah … yeah–do you see–yeah–yeah yeah! Ha! Ha! So I said to–fine with me–good stuff–yeah yeah yeah–yeah–yeah–O.K. Fine. Yeah yeah! Ha! Ha! Pretty cool!

GIRLS’ TABLE

(BRENDA in cheerleader costume, MARY in a dress somewhat influenced by latest hippie fashions)

Yes! Giggle, giggle–so I told him–yeah yeah–giggle!–what did–yeah–no! But if–yeah yeah yeah–O.K. Yeah yeah–I see now–but what if–hey look at–where? Yeah yeah–oh yes! Fine with me.

ISAAC

(Clutching a copy of Kierkegaard’s complete works, and The Freedom of Reason by Konstantin Kolenda)

In the end, man must face his utter loneliness and choose his freedom in a reasonable manner.

(Sits on Jumbo Burger counter and reads menu aloud)

To be or not to be, that is the question … Oh, what a rogue and peasant slave am I!

MARY

(Stands up, goes to audience, pleading)

In this world of unmitigated sorrow and despair, how can we survive … to be or not to be … we’re alone, all of us … it’s original sin that’s done this to us. We’ve got to wake up.

(MARY and ISAAC return to their seats without noticing each other.)

JERRY

Getting double-edged super roundabout twelve-inch dual side glasspacks for my Cuda.

ISAAC

Fine.

BRENDA

Imagine the principal throwing me out of the school for my dress being too short! I’m so mad I could just burn up!

MARY

Serves him right.

(ISAAC and JERRY notice BRENDA and MARY at the other table. Magical silence.)

JERRY

Say, look at da knockers on dat cheerleader babe!

ISAAC

What a noble expression of deep suffering, of tragic commitment to life, lies on the other one’s sweet face–like a soft veil, ready to be plucked off by–me …

(Lights dim. WAR CORRESPONDENT comes from behind counter and steps around the frozen figures of the four.)

WAR CORRESPONDENT

And so it began. On a small scale at first, but the evil grew. Isaac and Mary signed a mutual defense pact just three days later. Jerry and Brenda signed a treaty of non-aggression the next day, and later became allies. And so the sides squared off and waited … eighteen short months … before the killing began …

(Exit WAR CORRESPONDENT. Curtain.)

ACT TWO

(High school basketball game at halftime. Usual paraphernalia of high school gym, also decorated for The Big Dance. The WAR CORRESPONDENT kneels in the center of the deserted court wiping up a pool of blood. In the crowd milling around the edge of the court, ISAAC appears in Hamlet garb with upraised sword.)

ISAAC

(lofty)

Now might I do it pat, now he is praying.

And now I’ll do’t. And so he goes to heaven.

And so am I revenged.

(normal)

Yes, man is alone. He must take the burdensome responsibility of his own freedom, destroying all Establishments and those who would interfere with his emotional urges, the urges to negate life in all forms and paradoxically exploit life at the same time. Thus …

(WAR CORRESPONDENT disappears into the crowd. Cheerleaders, led by BRENDA, appear and dance. ISAAC stares in lustful admiration.)

LOUDSPEAKER

And so Jerry North, star basketball player, is reported in critical condition after his serious injury on the court tonight …

CROWD

Ohhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh

hhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh!

MARY

(Appears beside ISAAC)

What happened to poor Jerry?

ISAAC

So ’tis thee, thou bitch! My best friend Jerry, if thou must know, was smashed on the head with the pom-pom of one of thy fellow bitches, that cheerleader Brenda!

MARY

Thou meanest not my best friend Brenda!

ISAAC

Yes, your best friend Brenda killed Jerry ruthlessly and forever, just as you killed me ruthlessly and forever when you threw my abundant love into the toilet and flushed it, me, and all my dreams down into that dank morass of excrement and despair! All you ruinous bitches are the same. Get thee to a nunnery!

MARY

I will, thank you. Oh poor Jerry! Such a hero in the face of life’s tragedies! Such a manly hero!

(Runs offstage.)

JERRY

(Offstage, screaming)

Told da bitch I loved her! What the hell more does she want! Just a cock-teaser, da bitch!

(Twenty feet apart, ISAAC and BRENDA begin to exchange a long meaningful stare. As BRENDA drops her pom-pom and ISAAC drops his sword, both moving slowly towards each other with wide eyes and open mouths, the WAR CORRESPONDENT appears from the crowd with a director’s chair. He places it between ISAAC and BRENDA. A weary helplessness on his face. Slowly he takes out pencil and notebook and begins taking notes.)

ISAAC

(blushing and stammering)

Fair, thou … tender beauty and … miraculous sweet-scented night … the rose-bud May … ne’er so abundant in … joy and … fresh growth …

BRENDA

Why is it you’re so quiet? Don’t you like me?

ISAAC

Well–er–I–ah, well sure, but well … I … ah–well you see, I’m a–a philosopher of sorts–I–ha ha …

BRENDA

You can’t philosophize all the time, can you?

(sweet laugh)

ISAAC

Well …

BRENDA

Come …

(ISAAC and BRENDA fade into the crowd, which is lowly murmuring. JERRY and MARY, arm in arm–bandages on JERRY’S head–walk past and also fade into the crowd. WAR CORRESPONDENT stands up.)

WAR CORRESPONDENT

Well, I’m sorry about shocking you with all that gore and violence, but–it was necessary, to show how horrible the destruction was …

(pause)

But it wasn’t quite as simple as what you just saw.

(pause)

Though originally staunch allies, Isaac and Jerry fought bitterly over the rights to the borders and the natural resources of Mary and Brenda. Mary and Brenda, on the other hand, sought trade and the military protection of the supergiants Isaac and Jerry. None of the four powers could decide which alliance was most favorable to the changing circumstances, and so shifting alliances and terrible imbalances of power were the order of the day for the next four years. And that’s a lot of days …

(pause)

At any rate, the four powers, realizing the unbearable casualty rate and supply losses of their conflict, finally agreed to the Big Four talks which took place in Geneva, Switzerland …

(Exit WAR CORRESPONDENT. In the background, crowd’s murmuring voices. Curtain.)

ACT THREE

(Harris High school classroom. Thirty desk-chairs arranged in a circle. Blackboard, on it two calculus problems and the complete “To be or not to be” speech. Also “Freedom of Reason reports and Kolenda biographies due Monday.” The Big Four sitting at chairs. No one else in room, except silent WAR CORRESPONDENT at teacher’s desk.)

ISAAC

(simply, quietly)

Man is alone in the midst of an absurd game. Man must break free of all role-playing, all absurdity, all camouflage of his true multi-faceted self. Man must be free. Thus …

JERRY

Shaddup, for Chrissake … now let’s get down to business.

BRENDA

(To ISAAC)

Thou owest me an apology, thou rotten bastard.

ISAAC

O that this too too solid flesh …

MARY

What about my letter?

JERRY

What letter?

MARY

The letter I wrote my whole life into and which I must have back in order to regain my reputation–

JERRY

Oh that one. I lost it.

MARY

Oh no no no no no no no!

JERRY

Whoever finds it will mimeograph it and send it to all the top leaders of the world.

MARY

(in hysterical convulsions)

Oh no no no no no no no!

BRENDA

What did the letter say?

JERRY

It said “Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year from your darling Mary.”

MARY

Aohyieeeeeee!

(She rushes to the window. ISAAC grabs her arm.)

ISAAC

Wait, beloved Mary. I love you, divine Mary. Stay with me, beautiful Mary. I’ve always loved only you, darling darling–

(MARY jumps out the window.)

Hmm. We’re six floors up.

BRENDA

It’s me he loved.

JERRY

No! You loved me!

ISAAC

Well …

BRENDA

No, he loved me!

JERRY

No, he never loved you, nor did you he!

ISAAC

Well …

BRENDA

No, he loved me, but I never did love you, and he loves me still, and I do not love you now!

JERRY

No, not he, but me you loved. Not you he, but you me, not he you ever, but pretends you, though I love you now as always–

ISAAC

Well …

BRENDA

What the hell!

(To ISAAC)

Why are you so quiet?

ISAAC

I–er–ah–well, I’m a–philosopher of sorts …

BRENDA

Come …

JERRY

Not if I can help it!

(Slaps BRENDA, who cries.)

Now cut the crap and let’s get down to business. Tell Mary to get back in here and we’ll review the complaints. If we can get Mary and Isaac to agree to agree, then Brenda and I–

ISAAC

But Mary jumped out the–

JERRY

So? Tell her to get back in here.

ISAAC

But you don’t understand …

BRENDA

(bitterly)

All either of you ever wanted was my body! Well I’m leaving!

JERRY AND ISAAC

Stay, I love you dearly, my darling, if you only knew how dearly, my darling–

BRENDA

The hell with you!

(Gets up to leave. JERRY embraces her with mad passion.)

JERRY

Oh how dearly, my darling–

ISAAC

(fiery rage)

Thou shalt pay! Out sword! Make hamburger out of this knavish chap!

(Stabs JERRY repeatedly.)

JERRY

I regret …

(Dies)

ISAAC

Dead, dead for a ducat, Polonius! Dead, dead for a banana, King Claudius! Thou knavish hamburger!

(Throws JERRY’S body out the window.)

BRENDA

Oh how horrible! In the end how regrettable!

ISAAC

(comes to his senses)

What?

BRENDA

And now I suppose you’ll want to rape me for your victorious plunder!

ISAAC

(still dazed)

Why, not at all, fair maid.

BRENDA

(disappointed)

That’s all I am to you, a lowly scrubwoman! You never loved me!

ISAAC

Why, that’s untrue.

BRENDA

Then you would rape me for your victorious plunder.

ISAAC

Victorious plunder? Where did Jerry and Mary go?

BRENDA

(angry)

Out for a walk, the rotten bastards.

ISAAC

“Jerry and Mary.” That’s cute, like a little poem. Rhymes.

BRENDA

“Brenda and Isaac.” Trash!

ISAAC

I guess so. We should finish our meeting. Call in Jerry and Mary, that poetic twosome.

BRENDA

They went for a walk.

ISAAC

Call them here.

BRENDA

Don’t you understand?

ISAAC

Just call them–

BRENDA

Don’t you understand?

ISAAC

(thinking)

Let’s go for a walk.

BRENDA

All right …

(They walk to the window.)

ISAAC

You first.

(Curtain)

EPILOGUE

(Exactly the same as in prologue. WAR CORRESPONDENT enters, moves more tiredly than before, stares at the ground for a minute, looks at his watch, looks at notebook, throws notebook away. Looks directly at audience. Broken voice.)

WAR CORRESPONDENT

This … is all that’s left …

(Slow foot-dragging exit. Curtain.)

copyright 2010 by Michael D. Smith

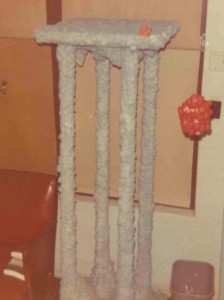

While my visual art has primarily been geared to painting and drawing, I occasionally do some sculpture. Three-dimensional design is high energy and compelling. The factors of gravity and balance are a delightful challenge, and they ground me in what’s real. Instead of a painting exhibit, I offered to do a January 2011 sculpture exhibit at the Park Forest Library in Dallas, primarily because this branch has four glass cases excellent for displaying sculpture, but not so much for paintings, which have to be small and propped up in four 3-D spaces each about 24” x 24” x 48”.

While my visual art has primarily been geared to painting and drawing, I occasionally do some sculpture. Three-dimensional design is high energy and compelling. The factors of gravity and balance are a delightful challenge, and they ground me in what’s real. Instead of a painting exhibit, I offered to do a January 2011 sculpture exhibit at the Park Forest Library in Dallas, primarily because this branch has four glass cases excellent for displaying sculpture, but not so much for paintings, which have to be small and propped up in four 3-D spaces each about 24” x 24” x 48”. Sculptures have always been fun and easy to make because I’ve rarely thought of them as “art,” just a sort of glorious 3-D exercise, and my materials are frequently leftover wood from constructing painting stretchers or bookcases, offhand debris that doesn’t seem like expensive art supplies. But they can be glued and nailed and painted. They are balanced slabs and struts, with right angles dominating, like demented architectural models. Their meaning is simply themselves; they’ve never needed to express emotions or philosophies. And when they outlived their usefulness, or collected too much dust or became household clutter, I’ve easily deactivated the things, often using their wood for new sculptures. Most of my sculptures no longer exist.

Sculptures have always been fun and easy to make because I’ve rarely thought of them as “art,” just a sort of glorious 3-D exercise, and my materials are frequently leftover wood from constructing painting stretchers or bookcases, offhand debris that doesn’t seem like expensive art supplies. But they can be glued and nailed and painted. They are balanced slabs and struts, with right angles dominating, like demented architectural models. Their meaning is simply themselves; they’ve never needed to express emotions or philosophies. And when they outlived their usefulness, or collected too much dust or became household clutter, I’ve easily deactivated the things, often using their wood for new sculptures. Most of my sculptures no longer exist. Because I now see the sculptures as important, I gave them their own section on sortmind.com. The sculptures are in no particular order, but the seven beginning on page four of the index are a representation of some of my early work.

Because I now see the sculptures as important, I gave them their own section on sortmind.com. The sculptures are in no particular order, but the seven beginning on page four of the index are a representation of some of my early work. But I can just imagine the gravity, weight, balance and cost issues inherent in moving to much larger work than that. Factor in X again (plus Y = rural Texas farm to store all this stuff in the sun and the rain) and I would love to explore some larger sculptural issues.

But I can just imagine the gravity, weight, balance and cost issues inherent in moving to much larger work than that. Factor in X again (plus Y = rural Texas farm to store all this stuff in the sun and the rain) and I would love to explore some larger sculptural issues.