The First Twenty Steps in Paperback

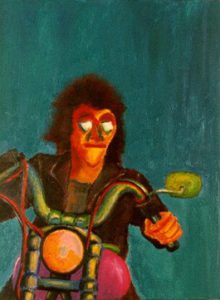

I’m not sure this is the protagonist, Harry Allen, but I drew him or someone today and there he possibly is. The novella chronicling his first day out of prison, The First Twenty Steps, is now available in paperback from Sortmind Press, and can be purchased at:

I’m not sure this is the protagonist, Harry Allen, but I drew him or someone today and there he possibly is. The novella chronicling his first day out of prison, The First Twenty Steps, is now available in paperback from Sortmind Press, and can be purchased at:

eBook versions are also available at both sites.

The book begins with crime and slips into science fiction. Harry wanders the foggy downtown streets of One-West at one AM, unaware of the ordeals and transcendence he’s about to stumble into …

All I had was two hundred bucks and my freedom, but as I listened to my boots slapping on the damp sidewalk I had to admit I didn’t know what to do with either of them. All I knew how to do was wander in the mist at one in the morning. Which was probably why I’d wasted one‑fifth of my life in prison. Hell, maybe I’d wasted the whole thing.

All I had was two hundred bucks and my freedom, but as I listened to my boots slapping on the damp sidewalk I had to admit I didn’t know what to do with either of them. All I knew how to do was wander in the mist at one in the morning. Which was probably why I’d wasted one‑fifth of my life in prison. Hell, maybe I’d wasted the whole thing.

Other people seemed to know the tricks that got you what you needed. They figured out how to get jobs, apartments, and cars. And they stayed out of trouble. And look at me, out of the pen for maybe eleven hours. Sons of bitches like Eric and Ronnie had to be attracted to me.

I needed to get back to Drulgoorijk, thirty miles to the east, and join up with my brothers again. They hadn’t visited me in a couple years, but I’d read enough about them in the papers to know that the Defenders were still alive. And I needed to get a bike in a hurry so I could ride with them again. I hoped they remembered me.

But the point was that the only way I could think to get a chopper was to rip one off. And I definitely had to stay away from the extra‑legal activities right now. I wasn’t about to risk another six years down the tube. But without a job, and the apartment that went with the job, and all that insanity, how was I going to get a bike? Sure the Rehabilitation Commission said it was going to help out, but I was sick of dealing with those soulless twits. And I’d already lost the address of the halfway house they’d wanted me to sign my soul over to. Hell, maybe it would be easier to rip a bike off after all and be done with it. Take my chances.

I balanced on a broken curb on a rundown street where most of the boarded up paint stores or oil change shops were waiting for demolition crews. Fifteen blocks east, beyond the Spaceship, the new skyscrapers of downtown One‑West rose into the clouds. I figured a storm was building.

I balanced on a broken curb on a rundown street where most of the boarded up paint stores or oil change shops were waiting for demolition crews. Fifteen blocks east, beyond the Spaceship, the new skyscrapers of downtown One‑West rose into the clouds. I figured a storm was building.

I had to grin in disgust. They say the criminal always returns to the scene of the crime‑‑and I hadn’t even realized I was doing it. But here I stood in front of Disc Engineering. It was hard to believe I used to unlock the glass door down that stairway at 7:30 every morning. A bit further was the parking garage where I’d pull in my old Harley after the morning freeway ride in from Drulgoorijk. The garage was asphalt poured over the contours of little mounds, with the two‑story brick structure of Disc Engineering mounted haphazardly on pillars above the rolling surface, the center of the building open to the sky. One reason I got here first every morning was to make sure I didn’t get one of the spaces exposed to sun and rain. My bike’s electrics definitely didn’t like rain.

It didn’t seem possible that I’d ever worked here. It was a wild place, its labyrinths filled with engineering documents, computers, engineers, salesmen, visiting presidents of multinational corporations. I just drifted into that job. Could I ever have gotten it on my own? Would I ever have thought of applying there? No, it was Melissa who got me that job‑‑Melissa whose dad was head of Planning. I’d started there eight years ago feeling like a sucker, trying to please my girlfriend, too wrapped up in her to understand she was trying to wean me away from the gang.

I didn’t realize until way later how much she hated the Defenders. But the feeling was mutual‑‑the gang hated Melissa too. And they were down on me until I got it through my head what was important. The gang. My brothers. So I split with her, but for some reason I kept the job. Her dad was glad we broke up. After a while he even took a liking to me. I got to be an Associate in the Planning Office, but again, I drifted into it without knowing why. Guess I was having a good time. The gang thought I was crazy, making it as a white collar worker, using my head to churn out concepts while Danny and Pete and Rick and all the rest worked in garages and machine shops. But they didn’t complain about the parties I could give, all the extra beer and dope we had, all the gasoline and bike parts I could come up with when everyone else was broke. Damn, we had some great times.

I didn’t realize until way later how much she hated the Defenders. But the feeling was mutual‑‑the gang hated Melissa too. And they were down on me until I got it through my head what was important. The gang. My brothers. So I split with her, but for some reason I kept the job. Her dad was glad we broke up. After a while he even took a liking to me. I got to be an Associate in the Planning Office, but again, I drifted into it without knowing why. Guess I was having a good time. The gang thought I was crazy, making it as a white collar worker, using my head to churn out concepts while Danny and Pete and Rick and all the rest worked in garages and machine shops. But they didn’t complain about the parties I could give, all the extra beer and dope we had, all the gasoline and bike parts I could come up with when everyone else was broke. Damn, we had some great times.

But as I passed alongside Disc on Thornton Street I wondered if I could ever have that sort of life again. Danny had been the last to visit‑‑two years ago‑‑and even then I could see he was drifting away from me. All those years in the pen had broken something‑‑and none of us knew why the law had come down so hard on me, why I’d been handed six goddamn years. Christ, there were murderers who’d come to One‑West after me and left years before I did. What had I done that was so bad? Why had my buddies deserted me?

And though I didn’t have a Melissa now to tell me what to do with myself, I did know I’d never try for another job like I had at Disc, because it would always remind me of six years at One‑West, a lot of it spent in solitary for that stretch of time about three years in when I took to punching out guards and fellow inmates. Although it sickened me to admit that Danny and Rick and the rest probably didn’t care one way or another if I ever showed up again, I knew I should probably try to get a job working on bikes or cars and scrape up enough cash to buy a huge chopped Harley. I had to get back to those guys. Hitting all those bars on the West Side of Drulgoorijk every Saturday night, picking up all those chicks, those had to be the best years of my life. I had to do whatever it took to get back to them.

One night when we were messed up on acid Danny and I had talked about what it meant to be a biker. When you’re a biker, Danny said, you’re set apart from the mass of citizen losers who’re just crapping around with their lives, stewing in all their little worries and never having any real fun, never really laughing, never really getting their rocks off. I told Danny it was like bikers got to climb up on this catwalk that was twenty feet above that whole gray ocean of mindless jerks. Bikers were noble people, and they got to walk on this catwalk made out of bright red steel girders and have all the fun they wanted up there.

One night when we were messed up on acid Danny and I had talked about what it meant to be a biker. When you’re a biker, Danny said, you’re set apart from the mass of citizen losers who’re just crapping around with their lives, stewing in all their little worries and never having any real fun, never really laughing, never really getting their rocks off. I told Danny it was like bikers got to climb up on this catwalk that was twenty feet above that whole gray ocean of mindless jerks. Bikers were noble people, and they got to walk on this catwalk made out of bright red steel girders and have all the fun they wanted up there.

Danny loved the idea of the catwalk, and agreed with me that one of the neatest things was being able to look down on all the losers dying in the mud below and be glad you had the guts not to be one of them. “It only takes twenty steps up,” we used to tell each other whenever the other was bummed out, and it’d remind us of the acid trip and that stewing in all that trivial crap was for common people, not us. Maybe that was one reason Danny and the rest were turned off by my Disc job‑‑maybe they thought I was selling out, crawling back down the steps to wallow in common fears like everyone else.

I turned back to the bizarre shape of Disc Engineering. Dammit, was it true? Had I forgotten the twenty steps? Had Melissa gotten me back to being some common dweeb? I looked for the Spaceship west of downtown. All night long the damn thing had been mocking the mess I was in. Maybe it knew I was a common dweeb after all.

I’d seen pictures of it in the papers, but never the real thing, though the prison was only a couple miles from downtown. One businessman was financing the Spaceship. For months people had thought the Episcopalians were erecting a cathedral tower on the site where their old church had burned down, but it turned out the Episcopalians had sold out long ago, and Richard Mullein had bought the property and finally declared that he was actually building a spaceship on it. It had been a scandal a couple years ago, with the government of One‑West demanding that all work on the Cathedral, as everyone still called it, be stopped immediately.

But Mullein, who owned vast portions of One‑West, Drulgoorijk, and the two counties containing them, had managed to strike a deal with the city. He said his Spaceship really would be a cathedral, a nondenominational place where all could worship what he called “the Great Creative Force,” and though he admitted he had wanted to build a sixty‑story spaceship on the outskirts of downtown One‑West, he now promised that, in deference to public safety, and the insurance rates on all those new buildings downtown, he’d never launch the thing. “I just want to be indulged in this one whim,” as he’d put it. “Can’t an aging billionaire be allowed just one whim?”

Most people knew that was crap. First of all, Mullein was only thirty-one years old. Second, nobody, including the city fathers of One‑West who’d nervously accepted his demands, had any doubt that the day the Spaceship was finished, Mullein would blast it off. And if it rose three hundred feet, veered sideways and blew up downtown One‑West, well, Mullein could pay for it.

Rising from the center of four white domes amid low buildings and seas of parking lots, the Spaceship was like a tall woman in a lacy white dress with both arms brought together above her head. A web of wires and tubes fed into the ship from four support towers. Floodlights drenched it all like an ice storm. Sixty stories up at the nose cone, I could see men on a platform working around open hatches. Vapor came out of nozzles around the ship. Oblivious to whether Eric and Ronnie might be roaming the area, I walked several blocks right up to the Cathedral Square, through the eye‑stinging light, into the acrid gases, past the men in white overalls with clipboards who frowned at me, shook their heads, and returned to work.

Nothing happened except that I’d forgotten my stupid problems for a few minutes. The Spaceship still mocked me.

copyright 2016 by Michael D. Smith

Comments

The First Twenty Steps in Paperback — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>