I finished the seven books of the Jack Commer, Supreme Commander science fiction series in 2021, and on what I felt was a strong note. I didn’t want to keep writing Jack Commer just because I was comfortable with it, and I knew that sooner or later any series usually goes downhill. To quote my blog from July 2022:

I finished the seven books of the Jack Commer, Supreme Commander science fiction series in 2021, and on what I felt was a strong note. I didn’t want to keep writing Jack Commer just because I was comfortable with it, and I knew that sooner or later any series usually goes downhill. To quote my blog from July 2022:

When the series begins to get overripe, create a new series in the same universe to retain reader interest.

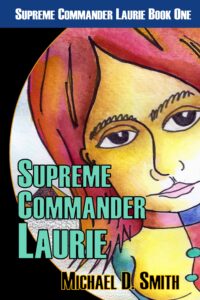

I’m now 111 pages through the first draft of Supreme Commander Laurie. I made a draft cover to anchor the book in my head, but it won’t be the final. You have to ask yourself whether you’re attached to your own cover as artistic self-expression, or if it can really help sell the book. But nobody’s thinking in those terms now.

A Minor Character Goes Major

One of my favorite characters in the Commer series, Laurie Lachrer, now steps into the spotlight. A minor figure with one scene and a few lines in Book One, The Martian Marauders, in 2034 Laurie was a nineteen-year-old USSF airman first class, a hanger technician involved with ship storage and security. She was mainly present to amaze everyone that Jack’s feckless younger brother John could possibly have snagged such a petite, stunning, super-intelligent redhead as a girlfriend.

One of my favorite characters in the Commer series, Laurie Lachrer, now steps into the spotlight. A minor figure with one scene and a few lines in Book One, The Martian Marauders, in 2034 Laurie was a nineteen-year-old USSF airman first class, a hanger technician involved with ship storage and security. She was mainly present to amaze everyone that Jack’s feckless younger brother John could possibly have snagged such a petite, stunning, super-intelligent redhead as a girlfriend.

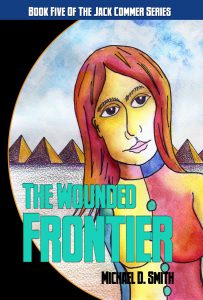

But Laurie was called out of obscurity for the series’ fifth book, The Wounded Frontier, where she stars on the cover. By the 2070s she’s abandoned a succession of responsible yet low-level USSF jobs to ascend to the exalted position of physician/engineer for the highest-tech Typhoon spaceships. In 2076 she’s sixty-one, but rejuvenation technology has kept her and most other series characters looking thirty to forty. Now Colonel Lachrer, sent to rescue Jack’s crew in a solar system thirty-four light-years away, matches wits with the Wounded, a nefarious race that blows up entire solar systems for artistic kicks. Though she’d secretly scorned Jack Commer as a naïve and outmoded leader, Laurie gains new respect for him as they work together in the last three books of the series. At the end of Book Seven, Jack promotes her to admiral and Supreme Commander of the United System Space Force.

The New Series

Supreme Commander Laurie is also the series title. I don’t have an overarching plot stretching across several novels, so I’m throwing everything I have into Book One. I’ll let Books Two and beyond take care of new themes and new life forces at their proper time.

I have extensive notes for this novel as well as a condensed overview, but since the thing is opening into spaces I hadn’t conceived of, and since I expect more of that, the notes are provisional and no book blurb can possibly form at this point.

At the end of the final Commer book, Balloon Ship Armageddon, Jack sent Laurie back to the Milky Way Galaxy to become Supreme Commander of the USSF. But as SCL opens, she finds herself inexplicably transported to the brand-new Typhoon VIII spaceship manned by Jack and his crew, who all volunteered to undertake a possibly suicidal mission to investigate the Unknown Irregularity at the Center of the Universe. So who’s in charge of saving everything now, Laurie or Captain Jack who just resigned his commission and turned over all his SCUSSF duties to her?

I also have to ask: am I really qualified to fix the Basic Problem of the Universe in this novel? I now see I need to walk Jack’s grand plans back a bit. I gave Laurie too many supernatural powers at the end of Balloon Ship Armageddon and so naturally the new plot mandates that she isn’t able to sustain those energy levels and will revert to normal human intelligence and fallibility. And I’ve got to push Jack back into a supporting character role.

The Laurie Conundrum

The next problem is that, while Laurie has a decent scene so far in these first 111 pages, her robot counterpart, Laurie 283, might be coming across as the main character. Laurie 283 was supposed to accompany Jack to the Central Irregularity but instead found herself in command of the ship Jack sent back to the Milky Way. The two Lauries–they’re both damn smart–quickly realize they’ve switched places but have no idea why. At this point I don’t either.

But as far as Sol is concerned, it’s the newly arrived robot who’s now Supreme Commander.

Then I find I’m having way too much fun with another walk-on character from the original series, Mickey Michaels, who was killed along with five other USSF crewmen when Jack’s foolhardy brother John elected to heroically ram the Typhoon I into Mercury at 4.3 million miles per hour. So read Book One to find out what I’m talking about. Michaels was a true expendable movie extra but he did have some lines; I just went back to the MS. and counted the fifteen times he spoke, usually to just chirp in some random comment.

How do I resurrect all the dead characters I want? Through the magic of Heroes and Villains of the Thirties robots, created in the 2040s to honor the soldiers and spacemen of the terrible years of Final War and time-travel combat with Alpha Centaurians. All these characters were commemorated in robot likenesses numbering in the thousands, and the last four Commer books make much use of the clunky contraptions. Since RoboticsMindPump, Inc. flooded the market with these HAVOTT collectors’ items, there are still many hanging around in 2076, when Supreme Commander Laurie begins.

So a Lt. Mickey Mal Michaels robot was created with as much detail as its programmers could find about the Typhoon I turret gunner, including his private online journal devoted to his secret aspirations to be a science fiction writer.

Thus several sections in SCL are novel chapters from robot Michaels’ new novel, Fathom the Doomboat Stars. He writes Chapter One from Jack’s point of view even though Jack is trillions of light-years away, yet Michaels insists his robotic mind is assessing billions of possibilities and coming up with the most likely conversation between Jack and a bewildered Laurie who’s just found herself on the wrong spaceship.

Michaels head-hops as he pleases in a florid, word-wasting, relentlessly obscene style. He becomes a Hunter S. Thompson-like commentator on action he thinks he understands, but so obviously doesn’t. His sections are absurd, but so much fun to write that they’re helping open up new territory. I find myself laughing out loud at some of his passages, always a sign of good energy flowing.

I don’t have to leave Mr. Michaels in this position, however. I just want to see where his idiot style takes me for now. I can tamp his sections down later and retain him as an ego-tripping narrator; there’s really no reason for such over-the-top obscenity other than that it describes his character, but I’ve seen how easy it is to replace four-letter words yet retain the same flavor.

Or I may choose to just rewrite his stuff back to standard fiction prose. In any case I have plans for Mickey Mal to surface later in the plot. I’m not terribly worried that he’s going to take over the novel. I can tell he wants to, though.

But hey, who’s really the focus of this thing? Laurie, Laurie 283, or Mickey M.? The series is Laurie. What’s she all about here? Before this book she’d always been a supporting character, albeit an extremely important one, but now she has to step up to be The One.

But a funny feeling is rising that Laurie is being held in reserve, that she’s not really ready for her part on stage yet, but that … it’ll come later in the novel, at the appropriate time. And that her unfolding will define the new series as completely separate from the original one.

Useful Planning Insights

A couple things I’ve noted in planning Supreme Commander Laurie can apply to any novel’s idea gestation period:

1) Initial plot notes can easily turn into a morality play, a shallow “How good shall triumph over evil.” I do try to go easy on myself at this point, recognizing that these first notes can be an expression of anxiety about how all this is supposed to work, and after all they’re just part of the entire process from first idea to published manuscript. As I settle down and let other energies start pouring through, this uneasiness fades away.

Plot notes can easily expand into numerous pages of dense, single-spaced musings. This creates confusing obstacles; navigating through forty pages of this is tiresome. But as I begin the novel, I start seeing which notes are writable and which are non-writable. I quickly discard the vague, low-energy notes and what remains is the fun fiction.

I also recently started creating an additional overview document for new novels; a couple pages long, they summarize each chapter in a sentence or two. I update this as the book moves along and it keeps the novel in focus. Later, when the book is done, the overview easily morphs into a novel synopsis.

2) You’re never disrespecting characters from previous novels if they don’t have a supporting part in the next novel in the series. Nor do you have to keep their whereabouts up to date. I’ve actually felt guilty about whether to record what’s going on with earlier characters in the Commer series, or if I need to get them a few lines on stage.

But this is simply not the case. Not only does the reader not care about the previous characters, the flow of the novel doesn’t need them either. They can just live in the background like any former staff member you used to work with. It doesn’t mean they didn’t have their useful function in preceding works.

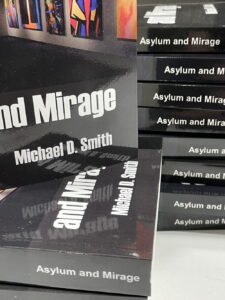

copyright 2023 by Michael D. Smith