A Writing Biography, Part IV: The Perfect Cube and Beyond

Recapping Part III as the Author Seeks Sympathy for How Terribly Difficult This Post Has Been

In rereading Writing Biographies I-III I’m struck by how they stand outside my usual self-description. I remember all that history, but it was as if someone else interviewed me and wrote it up. Yet I haven’t felt up to doing Part IV, even though I’ve collected notes for this post since September 2014. Gluing high school and college consciousness together is problematic; I don’t know who’s going to make sense of, then interview, the 1968 adolescent who graduates from Rice six years later as a semi-mature young man.

In rereading Writing Biographies I-III I’m struck by how they stand outside my usual self-description. I remember all that history, but it was as if someone else interviewed me and wrote it up. Yet I haven’t felt up to doing Part IV, even though I’ve collected notes for this post since September 2014. Gluing high school and college consciousness together is problematic; I don’t know who’s going to make sense of, then interview, the 1968 adolescent who graduates from Rice six years later as a semi-mature young man.

It was fitting to end Part III with December 1967. I definitely learned to write that year. The lengthy 1967 letters between me and my friend Sabin Russell showed both of us mastering language and quirky, open, satirical, conversational styles–but there was little spark of adult consciousness yet.

It’s tempting to throw in way too much into this post, but, just as with Biographies I-III, this isn’t the place to expound on America in the 60’s, historical events of the time, the history of the counterculture, or my own biography, Rice University life, or the billion themes and influences of these years. Or to deride how adolescent so much of this writing was by its author’s very nature. My story summaries below try to put them in the best light possible, but feel free to wince.

The Salamander Raid, Two Cube Stories, and Claiming the Writer

As mentioned in the Part II post, even as a fifth grader I had a sense of myself as a writer; I felt quite professional in turning out weekly science fiction stories. But during the Part III years I imploded and ceased to think of myself that way. Then 1968 opened up wondrously, and a sad little parable popped out in April, “The Salamander Raid,” about biologists hunting salamanders to extinction. The story marked a stunning change in self-awareness. I still didn’t dare call myself a writer, but I’d just written something that I recognized as a leap forward. Note that I also needed my English teacher to affirm that.

As mentioned in the Part II post, even as a fifth grader I had a sense of myself as a writer; I felt quite professional in turning out weekly science fiction stories. But during the Part III years I imploded and ceased to think of myself that way. Then 1968 opened up wondrously, and a sad little parable popped out in April, “The Salamander Raid,” about biologists hunting salamanders to extinction. The story marked a stunning change in self-awareness. I still didn’t dare call myself a writer, but I’d just written something that I recognized as a leap forward. Note that I also needed my English teacher to affirm that.

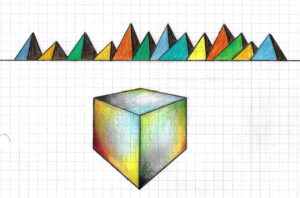

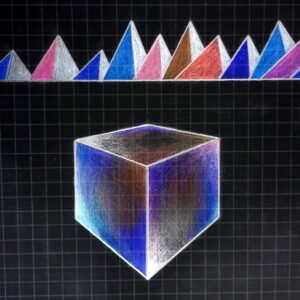

Another major step came in December. One night I lay miserably sick in bed, feverishly immersed in two events of the previous day; the first was the play I’d acted in for English class, Beckett’s Act Without Words, in which the main character stacks and sits upon various-sized cubes. The second was two red transparent dice I’d been examining before bed. I considered the number 27, a perfect cube, the cube root being 3. In the story that flowed out, a man invents and exhibits an absolutely perfect cube, not only in its 4” x 4” x 4” dimensions, but, much like the mathematical concept of a perfect cube, the object is implied to have mystical attributes. It’s so perfect it must be stored in full vacuum in a bell jar. But an angry young man (of course) smashes the jar, and the cube dissolves as the young man declares that “The world is not a place for perfect things.” I submitted “The Perfect Cube” as extra credit to my English teacher and her praise of it threatened to go to my head.

I knew I had something important here, though. As I wrote Sabin in June 1969: “I honestly feel ‘The Perfect Cube’ is the best thing I have ever written. Its dreamlike quality, its absurdity, its crazy logic, even the concept of absolute perfection as embodied in the Cube, have strangely appealed to me. Others have also found it interesting … And thinking deeper, I thought that it gave a sort of melancholy feeling that there is a serious basic flaw in life that cannot be corrected … Somehow I feel that I didn’t even write it, that it was written for me. It’s the weirdest idea I’ve ever thought of.”

It still seems scarcely conceivable how, even after coming up with “The Perfect Cube,” I failed to assert I was a writer. But the story propelled me onto new paths. The following month I wrote “The Individual,” about a man arrested for being a true individual, and March saw the high-energy satire “Farewell, Dear Toothbrush,” exploring the agony of consigning a loyal but spent toothbrush to the wastebasket. I also came up with an anti-war mockery of heroic World War II movies, “War is Hades!”

But “The Perfect Cube” nagged at me, and in May 1969 I followed up with “The Return of the Perfect Cube.” I have no memory of this sequel; all I can recall is that it was chaotic and echoed recent depression, and that I left it in penciled rough draft. Yet this didn’t matter. I’d at least attempted to get out something honest and up-to-date about myself. 2021 note to myself: Having something turn out poorly was just as instructive as having something turn out perfectly. It now strikes me as significant that in May 1969, after what was more or less a failure, I finally declared that I was a writer.

The Burning

Since “Farewell, Dear Toothbrush” and the sequel to “The Perfect Cube” no longer exist, I’ll take a slight detour to wonder at myself for burning some of this stuff in 1976, after reading Melville’s advice in Pierre, or the Ambiguities to burn your crappy writing so it mixes back into the unconscious, or whatever he said. I did get rid of some real junk, as well as rough drafts taking up space in my writing folders, but there’s much other writing I regret losing. In a couple cases I was able to reconstruct lost items, and I wrote off the loss of rough drafts as no big deal. I chose the victims in 1976 based on how adolescent they sounded to my so-called mature Akard Drearstone consciousness. I only burned items from 1968-1973, keeping everything from 1974 on.

Absurdity

My writing has always had absurdist elements. In looking over some old Sabin letters I came across a note about my 1969 high school assignment to research Theater of the Absurd and Ionesco’s The Bald Soprano. I felt I was coming home, in the same way I so quickly took to perspective drawing in the seventh grade. Why haven’t I seen this more clearly before? I’ve often declared, for instance, that my literary work Sortmind isn’t really science fiction; but the absurdist elements and the underlying satire make it impossible to regard Sortmind as a depiction of normal reality. Likewise Akard Drearstone, CommWealth, and The Soul Institute are in no way normal. The Jack Commer science fiction series is true to its space opera functions, but even then, the background is outrageous. This thread goes through almost all the stories mentioned in this post. It’s intriguing to note that anything attempting to depict fully straight reality is generally a failure.

June 1969 saw “Barney’s Missile,” in which Barney’s job is to sit in a cockpit atop a nuclear missile and ride it on a breathtaking journey to the enemy’s capital city. He doesn’t even know there’s a war starting, but is exhilarated with his space flight. That’s another story I burned; wish I still had it. In October came “The Mathematician,” in which a zealous math student is killed by police for hoarding math library books. In November’s “The Man Who Believed in Antarctica,” a derelict on a park bench tells our young narrator that he’s going to Antarctica because no war has ever been fought there. Not bad, but in retrospect a creative-writin’-teacher-pleasin’ sort of story. Then came another effort burned in 1976 which I wish I’d kept so I could reexamine its dismal dullness: December 1969’s “The Party,” a ponderous attempt to explain how a kid at a society party philosophically knows he must kill himself. I berated myself for this one at the time, noting that I was “groping for my emotions in my Roget’s Thesaurus.”

Voices

My senior year included a Fall 1969 creative writing class, which was demanding, highly beneficial, and life-altering, though it also had some of the drawbacks of any such class, like communal consciousness, sloganeering exhortations to write, sitting under trees to record “sense impressions,” and genuflection before Best Methods as Handed Down by Them. But the advice to keep a writing journal changed everything.

My senior year included a Fall 1969 creative writing class, which was demanding, highly beneficial, and life-altering, though it also had some of the drawbacks of any such class, like communal consciousness, sloganeering exhortations to write, sitting under trees to record “sense impressions,” and genuflection before Best Methods as Handed Down by Them. But the advice to keep a writing journal changed everything.

I’d initially resisted keeping a journal the same way I resist Facebook and Twitter now. A journal seemed antithetical to my writing methods, but I did see the need to keep writing ideas organized, so from November 1969 through January 1970 I made notes on 3 x 5 cards. Then I finally broke down and transcribed the cards into a silver spiral notebook, the first of what became scores of official writing journals. I had no journal voice at first, and the first notes were strident, mawkish, cute, or unwritable. Sometime in April 1970 I found my journal voice, though, and that was quite miraculous. I had a story-writing voice that was still pretty stiff and distant, though it could open up in satire. I had a Sabin-letter-writing voice that was loose and free and constantly developing. It was only slightly akin to the new journal voice, however. I won’t say that the journal voice was completely free; there were certainly things I wouldn’t discuss in there, but even those barriers broke down by the time I got to Rice later that year.

Through the high school years and into Rice I had yet another voice, deliberately pompous but strangely grounding: the aphorisms of Oliver the Giant Cat, which could be either satire or serious musings. Though I burned the fair copies of four binders of aphorisms, I found the rough drafts stored at my parents’ house in 1981. The five volumes of this era were: Live, and Strive for Happiness! (1969); Green Rainbows and Elephant Tracks in the Morning Mist (1970); The Odyssey of the Perfect Whirlpool (1971); Playground! (1972); and Spasm of Terror (February to October 1972, rough draft in a notebook, never finished).

Obligation Versus Energy

High school methods of writing included working off those early note cards or ideas in the new journal, but the flood of fresh awareness and early successes, and my willingness to open up to dreams like “The Perfect Cube,” meant that such notes no longer felt like the strained obligation of earlier plans, as, for instance, Summer 1967’s grim outline of writing projects. (Back to Part III if necessary.) Nevertheless, dire undercurrents of “should” continued for the next few years, probably up to the time of writing my novel Nova Scotia in 1973. I had not yet learned to follow the high energy; I hadn’t figured out that if an idea has no underlying energy, it’s not writable. Having energy doesn’t automatically make it easy, either. You have to be sensitive to where the energy is forming, and take on the task with vigor, whether it’s all spelled out for you or whether it demands experimentation, failure, and rethinking.

1970 stories were a mix of miraculously inspired plots, often from dreams, as well as those poorly-constructed obligation trips. January’s “Mr. Gray” was a somewhat sanctimonious riff on a man I saw drawing cash from a walk-up bank booth, notable for at least trying to muse on people outside myself. Published in our school literary magazine’s Brotherhood Issue (well-meaning middle-class high school kid consciousness), it seemed to bring me to the attention of the school as a writer. Hey, I did get a writing award and $5.00 in a school assembly at the end of the year.

March’s “The Bombers” came from a dream in which narrator-me and my friend plant bombs wherever we want, blowing up things and people as a practical joke, until one day I’m suddenly consumed with guilt. Another one burned to my regret. April saw a dream turned into the nightmare draft of “Underground,” in which soldiers must remove 40,000 dead Vietnam servicemen from an underground garage. Draft 2 in January 1971 was published in Rice’s literary magazine. At my former high school advisor’s insistence, in June 1971 I sent Version 3 to a literary magazine called The Leprechaun–but the submission came back “addressee unknown” and I joked that even the post office rejected my story. This was my first submission outside of school and the first time I’d seen Writer’s Market.

I also regret burning “Nice,” a precise document of where I was in April 1970, a bitter satire of everything being “nice,” including flooring our family Pontiac to 70 mph on a suburban road. But I discovered a new sense of revision consciousness with this one and kept polishing the draft over and over. My AP English teacher just wrote “Nice!” as a comment; I could tell she didn’t understand male teen angst.

I wish I still had August 1970’s “Another View of the Nonconformist,” for the same reason I’d still like to have “The Party.” This was a fairly long screed about the Man Alone in Nature who moves into a circular stone house in the woods. He considers it symbolic of ancient Greece and Primeval Truth–except that he’s haunted by the Race Track of Insane, Mechanized Society which he knows he’ll never escape. Yuck.

October 1970’s “Silhouette” was notable as the first story where I tried to write anything about sex. All I remember are stairs like an Aztec temple, and the guy and girl always finding obstacles and suffering. The writing was chaotic and unsatisfying. Of course I burned it in 1976, though I wish I still had it.

November 1970’s “Sam is Coming Home” was a major story, which I still have, taken from a nightmare in which I actually killed myself. Sabin was the model for the rational Sam in opposition to the troubled narrator. Writing this out seemed to fully answer a lot of adolescent torment. This story was carelessly shoveled into the first draft of Sortmind in 1987, though later mercifully removed.

Early Rice style followed the high school writing methods, with a marked resurgence of attending to obligations instead of following writing energy. Thus I had various plans I either forced myself to write or else abandoned in guilt. But apparently I got so tired of suffering my first semester at Rice that I assumed a sort of airy philosophical stance, which I consciously based on the admonition to be cheerful in Hesse’s The Glass Bead Game.

Early Rice style followed the high school writing methods, with a marked resurgence of attending to obligations instead of following writing energy. Thus I had various plans I either forced myself to write or else abandoned in guilt. But apparently I got so tired of suffering my first semester at Rice that I assumed a sort of airy philosophical stance, which I consciously based on the admonition to be cheerful in Hesse’s The Glass Bead Game.

January 1971’s “I Am a Freshwater Fish, and Water Diffuses In” is probably the best example of obligation-writing; I’d been down on myself for putting it off since the previous October. Something about a guy who designs toilet paper, then seeks some mystical experience on the beach. Yay. Burned 1976.

March’s “The Disgusting Bastard” was a decent story, albeit written in a smirking, creative-writing class style. The brainless (“unreliable”) narrator hears apartment neighbors Orange and Fitz arguing about Orange’s cringing personality, and Fitz eventually kills Orange. In “Flexible Contradiction,” Mortimer seeks what the title suggests at a society lady’s mansion, to everyone’s displeasure. A goofy story of no importance other than to illustrate my mastery of cheerful equilibrium.

May’s Total Annihilation: Camouflage! is a play in which a high school romantic quadrilateral is likened to negotiations between warring European powers. Funny, and a much better-executed illustration of my emotional distancing, it was later performed in two different venues at Rice and eventually became a blog post.

But my above-it-all posture would blow up over the coming summer. When I got home from my first year at Rice, I feared I was losing a good friend to drugs, and things got terribly serious. Fall writings started reflecting that, such as September’s “The Nearest, Most Easily Available Hurricane,” in which five boys drive to the city despite dire hurricane warnings. Two do psychedelics and when the hurricane hits so do the rest, going entirely crazy while the destruction mounts. All are killed but the narrator, who’s also poised to buy the farm any second.

October’s “Prelude, Hurricane, Disorientation, Upheaval, Winter,” has the narrator, after a semester of running mazes at The Institution, return home to parents who force him to work in a factory. Rebelling, he links up with his problematic girlfriend, but after severe weather destroys the entire area, he wakes up in his wrecked back yard to see the girl dead. Oh boy. “Elaborate Pantomime” laid out a Twilight Zone-like plot where a young student is teased about his preparations for nuclear war, but then it turns out to be real. Or did he just go psycho?

Wiess Cracks, Theater, and Collaboration

In the Fall 1971 semester of my sophomore year at Rice, I jumped at the chance to edit The Wiess Crack, abandoned by its current editor. I saw Wiess College’s lame humor magazine becoming a real literary investigation. This led to a new practice of collaboration with friends and other writers, in the Crack as well as in plays that Cosmic Productions put on over the following years. There were deadlines, improvisations, last-minute decisions, chores, successes and failures. The blog post for the Wiess Crack goes into much detail. The magazine dominated my last three years at Rice.

In the Fall 1971 semester of my sophomore year at Rice, I jumped at the chance to edit The Wiess Crack, abandoned by its current editor. I saw Wiess College’s lame humor magazine becoming a real literary investigation. This led to a new practice of collaboration with friends and other writers, in the Crack as well as in plays that Cosmic Productions put on over the following years. There were deadlines, improvisations, last-minute decisions, chores, successes and failures. The blog post for the Wiess Crack goes into much detail. The magazine dominated my last three years at Rice.

January 1972 saw “The Desirable Fuck,” a short horror piece about mindless drugged-up twits just a notch above barnyard animals. Over spring break I labored on “Father/Children,” the first time I included a father figure (in this case me playing someone killed years ago from hallucinogenic drug warfare, having left my mind-scrambled teenage kid narrator behind), and a disturbing conjecture about how future generations might cope with drug-induced brain damage.

During this difficult semester, which included a course postulating that I’d actually have time to read all of Dostoyevsky, I began dropping some deeper psychic anchors for both visual art and writing. The most astonishing writing wasn’t fiction, but thirty-one single-spaced typewritten pages of “The Story of My Life Since November 18, 1971,” a letter to Sabin which I composed on the electric Wiess Crack typewriter over three days during spring break, well into the early mornings. What began as an attempt to record three months of events since my last letter to Sabin turned into a turbocharged mission to write out everything. The letter was a gift from the universe that allowed me to reexamine and redefine myself.

That spring several of us decided to put on a couple plays, one of which was Total Annihilation, in which I played the War Correspondent. The experience of working with what we eventually called Cosmic Productions, and the energies released in collaboration and acting, sparked immense and welcome creative upheavals, and we performed the two plays three times in March to good crowds. This first taste of the theater has informed all my writing since then.

On reaching home in May, I worked at McDonald’s for a few weeks, determined to prove I could hold down a job and earn my own way in some small measure. I wrote a cycle of ten poems, centered around recent self-transformation, which I worshipped–and which Sabin lambasted as the writing of an “incurable romantic.” At night I hung out with my suburban Chicago buddies who seemed so well-grounded in earthy urban existence; they were refreshing, nourishing, and necessary. During sophomore year the level of superficial jokiness had increased between members of my Rice group, probably from Wiess Crack consciousness, the plays, and the Rice milieu itself, and I was forcefully struck by the contrast between the unpretentious, survival-oriented Chicago gang and my airy, jokey, intellectual Rice friends. Balancing between these two poles had a definite influence on my writing; possibly shifting back and forth between the two helped me eventually integrate comedy and tragedy. More below.

The Counterculture, Sloppiness, and Experimentation

It would take a completely different essay to factor in the role of late sixties’ cultural cataclysms, social, political, artistic, and musical, as they affected my writing. How they influenced the precise satire of “The Individual” or “The Mathematician” in 1969, versus what effect they had on my summer 1973 work on Nova Scotia, with the Watergate apocalypse blaring in the background, is difficult to calculate. Of course they were major stimuli–I can hardly imagine not having been blown away by seeing 2001 in March 1969–but I can’t help feeling that my writing trajectory wasn’t nudged too far by the culture around me.

It would take a completely different essay to factor in the role of late sixties’ cultural cataclysms, social, political, artistic, and musical, as they affected my writing. How they influenced the precise satire of “The Individual” or “The Mathematician” in 1969, versus what effect they had on my summer 1973 work on Nova Scotia, with the Watergate apocalypse blaring in the background, is difficult to calculate. Of course they were major stimuli–I can hardly imagine not having been blown away by seeing 2001 in March 1969–but I can’t help feeling that my writing trajectory wasn’t nudged too far by the culture around me.

Yet a certain psychic vagueness manifested itself during my interactions with freak and hippie culture, and though I still sought to honestly explore, looking back I can see where a sloppy style took hold. Maybe this arose from a need not to know myself, to stay unfocused, but I think it was also inspired by the ease with which rock music lyrics frequently veered into the dazzlingly incomprehensible. It was probably further influenced by counterculture authors emulating this trend.

So I blasted out a lot of blurry, pyrotechnic, experimental quasi-fiction, along with endless stream-of-consciousness harangues in the journal and on the typewriter through 1975. Not until September 1976, a few hundred pages into my novel Akard Drearstone, was I able to reconnect with clear prose. Melville may have been right after all; immediately after the great garbage can burning of old writing in the summer of 1976, Akard rocketed into astonishing unknown territory.

The important exception to this sloppiness, akin to medieval monks copying ancient Greek and Roman texts for the day when reason would return to the world, was my unbending dedication to brutally clear and expressive poetry, especially from 1971 to 1973. Every word, every punctuation mark, was carefully evaluated for maximum impact. I kept my precision intact in poetry and it would eventually return to my prose.

The original subtitle of this post was “Sensitive Stories Bludgeoned by the Wiess Crack,” but that isn’t a fair description of this era. Few of my stories could be described as “sensitive,” in fact, that description might only apply to “The Salamander Raid.” But I was always aiming for something serious. I considered humor a nice sideline, even though it was definitely part of my personality and was amplified in letters to Sabin. If I wrote a long poetic panegyric to Oliver the Giant Cat, or smirked out a “Farewell, Dear Toothbrush,” I thoroughly enjoyed the ballooning energy, laughing my head off as I reread and reread those pieces, but I didn’t think I should import that sort of flippancy into what I considered the serious stuff.

Even so, as outlined above, my writing had always included absurdist elements. Not for nothing was The Twilight Zone one of my two great childhood inspirations, the other being 1950’s Grade B science fiction movies. Dreams and their illogic were always a notable source for story ideas, and my best writing throughout this era usually had uncanny twists, distorted perceptions, and bizarre underpinnings. But it wasn’t humorous.

In any case I didn’t take well to numerous Wiess Crack contributions from my two main contributors, Bear and Joe, especially the last-minute ones I had to take that were slightly more advanced versions of the chuckle-along style of the old Wiess Crack mode I’d just finished overthrowing. Before long my vision of a serious literary investigation into the philosophical aspects of surreal consciousness was polluted by dull Rice boy “Gotcha Dumbass” entertainment; there was even a Crack by that title.

Despite what I just said, learning to collaborate with Bear and Joe, and finding gems in other writers, was worth the entire experience. Finishing up senior year with the masterpiece 200-Page Wiess Crack was a psychologically necessary summation of my entire Rice experience. Despite the final semester’s confusion and overwork, this Crack came out clean and direct. I finally did learn the lesson, as I wrote at the time, that “the editor must be a bastard.” By the end of my time at Rice I’d gotten the Crack where I wanted it.

Though I wrote funny things at Rice, I never truly accepted them. It wasn’t until I was thoroughly warmed up on Akard Drearstone, 1976-78, that I discovered how surreal, serious, and humorous elements could mix and support each other.

I’ve often wondered–through never terribly much, and even less since I’ve published several novels–what my style and content would have been if I hadn’t run into the counterculture. The high school style of discovery, distance, satire, and precision gave way to meandering, sometimes irresponsible light shows that may have been necessary experiments at the time but which also added a lot of self-sabotage to the works, and to the chance of finding publishers.

But musing how I might’ve kept high school precision might also be a way of wishing to have stayed a teenager, that I shouldn’t ever have grown beyond that. Well, life intervened and showed new paths. And if something pristine is dented along the way, that’s life as well.

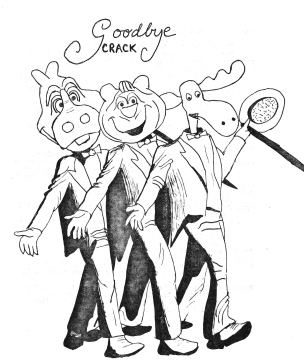

Fall 1972 through May 1973, my junior year at Rice, saw the second season of the Wiess Crack, done more leisurely and maturely. Major stories included October’s “Bloody Death Accident FUCK-UP,” in which our hero sinks into an annihilating death only to be transformed into a mystical entity, and January 1973’s “The Cleaveriad,” something of a novelette and of course based on our group’s incessant watching of Leave it to Beaver reruns. Young Beaver gets addicted to snorting pantyhose and shooting Drano, but at last cleans himself and embarks on a soul journey. The piece was thoroughly satisfying and dominated January’s 80-Page Wiess Crack. This writing was an exception to shunning humor–I just threw myself into this thing and loved the work.

Maybe I felt guilty for having all that fun, though, for within a month I’d returned to shoving out sterile, self-protective efforts like an untitled one-page masterpiece about a guy wearing cowboy boots and sitting in a restaurant watching things. Wow. But this late winter minimalism was badly shaken in the spring when a student in writing class astonished me–and I think the whole class–by doing the exact opposite, pouring out page after page of psychological and emotional insights into the lives of numerous fascinating, complex characters. So, hey, I tried the same with forty handwritten pages of “Five-Pointed Stars,” weaving a lot of male and female characters into an account of a serious car accident I’d walked away from the previous December. At the time I considered “Five-Pointed Stars” more experiment than art, but I note that I’ve never returned to the icy minimalist crap.

So, embracing fun and friends and fresh creation, that spring I collaborated with Joe, along with some good musicians, in writing Beaver’s First Fuck, a rock opera in which Beaver joins a cannibalistic hippie commune, murders his parents, and leads a revolution against the Mayfield bourgeoisie. This was glorious high-energy inspiration, and Cosmic Productions performed the rock opera in April at Wiess before a packed crowd. Imagine me, Gilbert, singing on stage. We also videotaped the production the following spring.

I had more fun collaboration over the summer as my Chicago friend Dan and I effortlessly spun out the plot of the novel Nova Scotia as we drove a panel truck to help a friend move. I quit my graveyard shift Dunkin Donuts job and, buying a 1940’s Royal Deluxe typewriter for $50, spent a month banging out the 116-page novel about Dan and Mike driving a Corvette at 350 m.p.h. from Chicago to Nova Scotia in one night in a demented quest to save the world. Writing a novel was immensely satisfying and answered so many ambitions. The second draft in spring 1974 served as a senior thesis, one of my forty Rice courses. Very fitting.

Kicked into the Future

Senior year’s Fall 1973 was a sober, serious time, with the background of the Yom Kippur war, the oil embargo, and Watergate. Fall writings of interest included October 1973’s “Political Revolutions,” from a dream of delivering newspapers to impossibly difficult rural locations. It emphasized dream logic and Wiess Crack readers liked it. In November and December I wrote The Fifty-First State of Consciousness, which I’ve always considered a real novel because it covers so much territory, even though it’s only sixty-three pages. Named like “K.” in The Trial, “G.” explores the fifty-first state of consciousness and links up with its Governor in the ultimate shopping mall metaphor for human consciousness. This was a heartfelt effort, if uneven in its only draft. But one of its later chapters was truly electric and has always seemed like the beginning of my modern novelistic consciousness.

Senior year’s Fall 1973 was a sober, serious time, with the background of the Yom Kippur war, the oil embargo, and Watergate. Fall writings of interest included October 1973’s “Political Revolutions,” from a dream of delivering newspapers to impossibly difficult rural locations. It emphasized dream logic and Wiess Crack readers liked it. In November and December I wrote The Fifty-First State of Consciousness, which I’ve always considered a real novel because it covers so much territory, even though it’s only sixty-three pages. Named like “K.” in The Trial, “G.” explores the fifty-first state of consciousness and links up with its Governor in the ultimate shopping mall metaphor for human consciousness. This was a heartfelt effort, if uneven in its only draft. But one of its later chapters was truly electric and has always seemed like the beginning of my modern novelistic consciousness.

Spring and Summer 1974 writings were a blur of short typewritten ideas and rough draft poems amid the hassle of The 200-Page Wiess Crack, a second draft and manuscript of Nova Scotia, and the Beaver videotape project. After graduating from Rice in May, I decided it was time for this new novelist to seek publishers, and I laboriously revised “Five-Pointed Stars” and a 51st State chapter, “Holy/Unholy,” for submission to literary magazines. Yet after researching some of these magazines at Fondren Library I got so depressed that I abandoned the attempt to enter what looked like a dreary, hopeless writing sweepstakes. I’d venture in again the following year.

In June 1974 I returned to my childhood space pilot Jack Commer in “The Martian Holes,” which covered the evacuation, in the face of the coming destruction of the Earth, of only the rich upper classes to Mars. A swashbuckling lack of focus, fun in itself, but not what I wanted to be doing. It still wound up, along with my 1968 essay on Jack for high school English class, in 2021’s The UR Jack Commer.

Amid plans for marriage, a six-week public health library job in Houston, a new motorcycle, Patty Hearst on the run, the Lester Quartz comic strip, Watergate’s finale and Nixon’s resignation, I relaxed over the summer, painting big canvases like Interstellar Wombat, Insect Brandishing the Jupiter Symphony, and Smiling Nancy–and I deeply relaxed about writing. Despite that ongoing sloppiness, the first parts of a long story, “Space, Time and Tania,” composed right before Nancy and I got married, were delightful. It was the start of regeneration and new exploring. I’d complete it in Dallas, revise it, and it would eventually find a publisher.

copyright 2021 by Michael D. Smith

Pingback:A Writing Biography, Part VI: Failures, Successes, Rhythms and Swerves, 1983-1994 – Sortmind Blog – Michael D. Smith