What would my or any current writer’s career have been like if there were no Internet or word processing, no eBooks or online publishers? Even if the invention of digital computing machines was inevitable, consider that there was no guarantee it would happen in this exact time frame–mainframe computers for calculating H-bomb parameters in the fifties, ARPANET in the sixties, personal computers in the seventies, the World Wide Web in the nineties, and the exponential growth of the Internet thereafter. Take away a few gifted individuals, a few insights here and there, slightly alter the history, and maybe all we take for granted now might not have gotten started until, say … 2033 … and in that case, what would you be writing now, and how? Let’s hope you wouldn’t be mimeographing little poetry chapbooks to hawk in used book stores!

What would my or any current writer’s career have been like if there were no Internet or word processing, no eBooks or online publishers? Even if the invention of digital computing machines was inevitable, consider that there was no guarantee it would happen in this exact time frame–mainframe computers for calculating H-bomb parameters in the fifties, ARPANET in the sixties, personal computers in the seventies, the World Wide Web in the nineties, and the exponential growth of the Internet thereafter. Take away a few gifted individuals, a few insights here and there, slightly alter the history, and maybe all we take for granted now might not have gotten started until, say … 2033 … and in that case, what would you be writing now, and how? Let’s hope you wouldn’t be mimeographing little poetry chapbooks to hawk in used book stores!

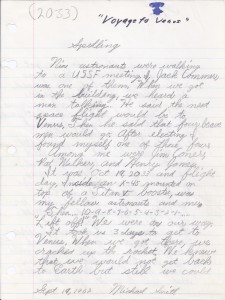

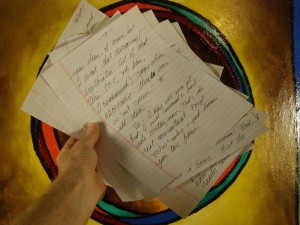

That rough draft typewriting seems so ancient. But consider that typewriters only came into use after the 1860’s and that Mark Twain is said to be the first author to submit a typed manuscript. Thus all the works before that were handwritten and submitted to publishers as such, even if dictated by the author to someone else. We see the final copy of an eighteenth or nineteenth century book and note its typeset print, but it’s hard to imagine Herman Melville handwriting Moby Dick. We see a photo of the First Folio and forget that Shakespeare set it all down by hand. Victor Hugo’s wife painstakingly wrote out copy after copy of the drafts of Les Miserables and Tolstoy’s wife did the same for War and Peace. What was going on in everyone’s souls as they performed these tasks?

Time

The top value of word processing that comes to mind is the scarcely believable amount of time saved as a novel morphs from rough draft to MS. without entirely new manuscripts to retype. You could hire a typist for the final typing of a submission manuscript if you had the wherewithal–but that still might take weeks or months, and then you’d be proofing it and negotiating about errors and changes.

For me the usual practice was typed rough draft, typed second draft, then typed third and fourth drafts of individual chapters needing further work, all with scrawled corrections. The rough draft was the initial vision with all its flaws. The second version, consisting of all good Draft 2 chapters plus all further revised chapters, was, hopefully, the essential expression I’d aimed at all along. After that came the dreaded typing of the manuscript, which also happened to include some revision as I went along. Yet I knew that all subsequent revision was forever frozen with each page pulled from the typewriter.

Aside from typed story manuscripts, a few of which went to forty pages, I only attempted two novel manuscripts. The first one, which at the time I considered the final version of my first real novel, Akard Drearstone, I abandoned in 1981 after 310 typed pages. I think the fact that I still had some seven or eight hundred to go was the main factor in helping me realize that the sprawling novel just wasn’t working, that I’d outgrown the thing, and that any further effort expended on it was a waste of life energy. But a feeling of incompleteness didn’t go away until I rewrote the novel decades later. If this first novel had been done entirely on the computer I wonder whether I wouldn’t have just called it done and submitted it the way it was. In a way it was good to feel what it was like to ditch a novel I’d sunk six years of my life into.

I did finish a 320-page typescript of my next novel, The University of Mars, and though this was an extremely dense and meandering work, it was an honor to mail off not only query letters and sample chapters, but in one case a manuscript box containing the entire novel. Of course good quality photocopies substituted for that holy manuscript.

Copies

In the case of my earliest stories, I mailed the original typescript and kept a photocopy. I only lost one original in the mail. But by the time I was several hundred pages into the rough draft of Akard Drearstone, I was getting paranoid about losing all my work to fire, flood, or the truly scary concept of novel thieves, and I would find various offsite places to store the novel when my wife and I went on vacation. I never felt I had the time or money to photocopy the finished 1,587-page novel, and for some reason the concept of carbon paper never entered my mind. But typing the second draft, in addition to greatly strengthening the novel, had the secondary benefit of more or less creating a copy. As I wrote my next novels I made photocopies of even the rough draft every few chapters. All this added up to quite a stack of paper and in recent years these insurance policies against loss have been cut into quarters for scratch paper, which I have an endless supply of.

In the case of my earliest stories, I mailed the original typescript and kept a photocopy. I only lost one original in the mail. But by the time I was several hundred pages into the rough draft of Akard Drearstone, I was getting paranoid about losing all my work to fire, flood, or the truly scary concept of novel thieves, and I would find various offsite places to store the novel when my wife and I went on vacation. I never felt I had the time or money to photocopy the finished 1,587-page novel, and for some reason the concept of carbon paper never entered my mind. But typing the second draft, in addition to greatly strengthening the novel, had the secondary benefit of more or less creating a copy. As I wrote my next novels I made photocopies of even the rough draft every few chapters. All this added up to quite a stack of paper and in recent years these insurance policies against loss have been cut into quarters for scratch paper, which I have an endless supply of.

The digital age of course enables us to make numerous copies of everything we write. I generally have six digital copies of my entire literary output, and create offsite storage by rotating two flash drives between home and work. Aside from the occasional dumb error where I accidentally copy a previous version over the current version, I’m fairly secure in my copies.

I still do make some prints. When I write the rough draft of a novel, I print each day’s work upon completion, and this I call Ur-Draft 1. What if civilization DOES come to an end right after I yank the most magnificent chapter possible out of the Void, and all electricity is gone? Well, I have my print copy and if and when electricity is restored, I can scan it in again.

I’ll reread the previous printed Ur-Draft session and scrawl over it in preparation for the coming day’s writing. Cleaned up, Ur-Draft 1 eventually becomes Draft 1, which I print as well, because by now I intend to put this novel to bed for a while and I want something to review offline at leisure. And of course the printed Draft 1 is now available for the End of Civilization–a win-win scenario for me, humanity in general, and whatever alien races eventually stumble across my dusty file cabinets.

Later on, Drafts 2-3-4 may just flow together. It’s all just revision and I really stop counting drafts, and printing is more or less wasting paper at this point. I might print the “final second version” in a paper-saving, Times New Roman 10, single-space copy, or I might wait until I finish the entire novel, just so I do have an “approximate final version” in print. I no longer print a final double-spaced, perfect manuscript for submission as I did even a few years ago. There’s no point to that, as submission will be electronic and despite the fact that my novel by this time is absolutely perfect in all respects, if accepted the thing is destined to be edited. In any case, I have those six electronic copies–and any email creates two more!

Mental State

I don’t know if I can accurately compare the mental state of typing my novels to my current electronic methods. It’s tempting to assume that in the past the entire process was more relaxed and more focused, but this may just be mistaken nostalgia that the past was always slower-paced. In fact I think we have always been pressed for time. My high school journal–before PC’s, digital videos, iPhones, tablets, texting and the Internet–records my complaint that life was moving too fast! But I think the main reason I can’t compare methods is that I’ve grown so much as a writer in the past few years. There’s simply not a proper control subject for comparison.

Certainly it’s easy to take on a lot of writing projects and work on them simultaneously. The computer contains all the projects and I can flit from one to another as desired. Yet it could be argued that anyone could do the same with pencil and paper. It’s just that the final result of a submission manuscript will take longer to prepare.

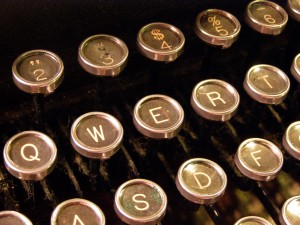

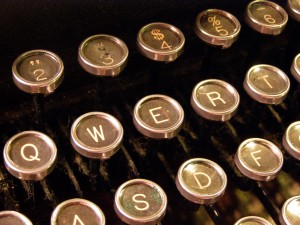

One difference which is subject to proof concerns the amount of typos I’m now able to generate with electronic keyboards. In fact, one reason I’ve mistakenly assumed that my current novels are error-free is that back in the typewriter days they pretty much were error-free. The physical act of typing on a manual typewriter forced me to be a fairly good typist–slow, never properly trained, but detail-oriented and willing to slow down enough to avoid the gut-wrenching moment when you realize a manuscript page is so mangled that, three-quarters of the way in, you angrily rip it out of the carriage and start retyping the whole infinitely-cursed thing. The technical term was a “devil page.”

A few years back I decided to read the rough draft of another of my ancient, unpublishable novels from the eighties, and about three hundred pages in I was struck by a descriptive paragraph that took up three quarters of a page. It was just meandering thoughts that would certainly disappear in a rewrite, but nevertheless I was struck by some well-written psychological insight and found myself rereading that paragraph several times. Then it hit me that there was something else odd about this paragraph of some 250 words: there was not a single typo in it. On the fly, rough draft meandering thoughts, and yet the left brain was sufficiently in control to keep the fingers accurately rendering these free-form ideas. Now I find I can’t type five words on the computer keyboard without squiggly red lines sprouting beneath three of them. And one deleterious result is that some typos remain nestled in the manuscript in perpetuity, as somehow I must still think I’m so detailed-oriented I can’t be making such mistakes–mistakes which somehow become terribly obvious once I see the published eBook. Best typo of this post so far: puibskluehr for publisher. Try making that on a manual typewriter!

Typing also had this psychological lift: in working through your narrative there came the moment when you were forced to admit that you’d typed to within a quarter of an inch of the end of a page. So you had to hold the coming character interaction in mind for a few moments while you yanked out the paper, fed in a new sheet, aligned it properly by temporarily loosening the carriage, numbered it at the top, and continued on your way. Each page was a psychic marker of advancement. Of course you can see your page count mounting in Word, but there’s no corresponding physical flourish.

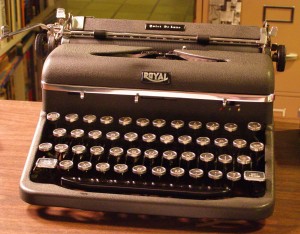

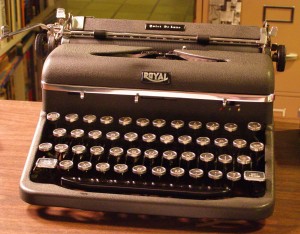

The accompanying photos show the 1940’s- era Royal I bought in June 1973 and which has processed in the neighborhood of twenty thousand sheets of paper. I did choose this manual typewriter in the expectation than an energy crisis would soon leave this world without electricity–while I of course survived, typing raw soul rough draft novels at some hippie commune, oblivious to the death throes of humanity. I never did warm up to electric typewriters, and I also managed to avoid even touching the plastic surface of any of the myriad “electronic typewriters,” stunted cousins of early PC’s, that appeared during the eighties. They looked simple and even seemed to be geared towards a writer like myself, but I never trusted them. But it was time to acknowledge the future in the form of our new 1989, $2,000 286 PC. Initially freaked by it, I went back to the typewriter for a sixth draft of a problematic novel chapter, but in the dawning celestial light of electronic revision and backup copies, I soon abandoned the Royal except for the occasional essay I still use it for–pages which I immediately scan and OCR.

The accompanying photos show the 1940’s- era Royal I bought in June 1973 and which has processed in the neighborhood of twenty thousand sheets of paper. I did choose this manual typewriter in the expectation than an energy crisis would soon leave this world without electricity–while I of course survived, typing raw soul rough draft novels at some hippie commune, oblivious to the death throes of humanity. I never did warm up to electric typewriters, and I also managed to avoid even touching the plastic surface of any of the myriad “electronic typewriters,” stunted cousins of early PC’s, that appeared during the eighties. They looked simple and even seemed to be geared towards a writer like myself, but I never trusted them. But it was time to acknowledge the future in the form of our new 1989, $2,000 286 PC. Initially freaked by it, I went back to the typewriter for a sixth draft of a problematic novel chapter, but in the dawning celestial light of electronic revision and backup copies, I soon abandoned the Royal except for the occasional essay I still use it for–pages which I immediately scan and OCR.

Revision

The ease of revising a final manuscript or even a published novel seems so obvious now, but it was extremely difficult if not impossible before word processing. If you were in the cycle of mailing and remailing your typed novel manuscript in the face of rejections, and eventually realized you wanted to delete twelve paragraphs in a given chapter, which would amount to losing say three pages, well, there was a way: retype all or most of that chapter and then type at the end of the half-done page 119, “continued on page 123.” But that really did look like crap. You could also add a page 123a if you felt you had something important to say between 123 and 124. But if you realized that two characters were too similar and would really work better combined into one, your typed MS. just became Draft X and you were now sentenced to retype three hundred new pages. And as far as a published work went, there was no incentive on anybody’s part to come out with a second edition of a novel.

Submission, Publishing, Marketing

I’d read books on the publishing industry in the seventies and eighties, but I don’t remember much about the time-consuming methods of publishing before computers. I do recall being in awe of Norman Mailer’s description in Advertisements for Myself about how he felt “as if finally I was learning how to write” on the galley proofs of his third novel, The Deer Park (1955), revising the entire style to fit a new vision of the book. His original publisher’s typesetters had forged that galley proof letter by letter from his typewritten and copyedited manuscript, and the proof was apparently intended to catch occasional typos, not to function as a platform for teaching an established author how to write! (But more power to him!)

In any case, the age of mailed typewritten manuscripts with self-addressed stamped envelopes is over, along with poring through the printed Writer’s Market and Literary Market Place for publishers, standing in line at the post office, dealing with handwritten corrections with proofreader’s marks, long delays, and no changes after certain points. Word count is now just announced by Word, as opposed to estimating it by counting words on a sampling of pages and taking an average. Formerly you could spend hundreds of dollars a year sending manuscripts by mail, but the cost of submitting a novel to a publisher, or self-publishing it, has come down to zero. In addition, everything is moving faster, and we can get near-instantaneous decisions: I once got a rejection four and a half minutes after submission. Well, at least we can move on.

I did experience some of the publishing hassles of the pre-Internet age. As editor of the Wiess Crack at Rice University, I created each issue’s cover and typed the stencils for the Gestetner printing process. I had to carefully calculate the pagination on long editions. For instance on the massive finale, the Two Hundred Page Wiess Crack, the stencil required page 68 on the left and page 133 on the right, so in typing the pages in order I had to keep track of which stencil would need to become available again for its counterpart page, and make sure the stencils were in the correct order for double-sided printing. After printing I collected the immense piles of pages and folded and collated them, often by having parties where I had to carefully recheck the work of my beer-fueled assistants. Then I would “market” the two hundred or so final copies by placing them at the eight different residential colleges. Funny how the free copies were so enthusiastically received and discussed around campus. Funny how the two hundred-pager, which for reasons I can’t remember I had to price at fifty cents, only sold a hundred copies … funny how I realized I hated sitting in the Quadrangle feebly trying to interest passersby into parting with fifty cents, and wound up writing a check for $150.00 to Wiess College and retaining a huge box of useless two hundred page Wiess Cracks.

While marketing may still seem like an endless, lonely, and hopeless chore, consider that there would have been next to zero marketing from the publisher for your typed novel accepted for publication in 1983–and in fact there won’t be marketing from the publisher for your 2013 first novel either. Except for the well-established writers it’s always been do-it-yourself, and now we have all sorts of mostly free tools to accomplish it, like email, Twitter, Facebook, review sites, blogs and web pages. Just as we’ve been told to never, never give up on submitting our works–which is absolutely the only way to go on–we must never, never give up on the marketing.

Does It Make for a Higher Quantity of Novels? Quality?

Has the ease of electronic writing resulted in more novels produced? Common sense would say yes, that not having to type three or four separate three hundred page drafts of one novel means that in the same time period we ought to be able to write three or four novels. And since series fiction is becoming more and more popular, each novel can flow from the previous one. New characters don’t have to be created over a long gestation period, including many pages of notes and musing and entirely new plot backgrounds. The ease and zero cost of submission also frees up resources better spent on writing.

The idea of never getting feedback except from a few friends may have limited pre-Internet authors to a handful of experimental novels. But with the stigma of self-publishing easing, with sales demonstrating that novels that were once slush pile rejections do have merit, it seems that people are more willing to write books they know can be published. And teens and young writers may no longer feel they must wait out some apprentice period in the hope of some vague breakthrough decades down the line.

Then again, who knows how many handwritten or typewritten manuscripts have been composed over the last two hundred years? How many were submitted and rejected, how many were locked in desk drawers? How many wound up in landfills? How many were godawful and how many were okay and how many were inspired? Did an unpublished writer tend to concentrate on fewer novels, maybe just two or four, as compared to a modern writer of a fantasy series who may have ten or fifteen eBooks out there already? Though Kafka did publish some stories during his short life, he was an unpublished novelist with just three novels–as far as we know!

With speed of composition increasing, one may feel freer to experiment and learn by attempting new novels as opposed to working the same one over again and again. If Novel One doesn’t work, try Novel Two. Don’t bother rewriting, just keep moving. Authors may be feeling like TV scriptwriters coming up with an entirely new script every week. Whatever the case, it does seem that the creative energy is ramping up. The main drawback, it appears to me, is that the joy of time-saving might easily turn into raw haste, with a corresponding decline in the quality of our work.

So which is it, new rising creative energy, or half-done work blindly flung into the World Publishing Machine? While it may be tempting to assume that the increasing quantity of eBooks means a corresponding decline in quality, consider that most writers really do want to keep improving. Although we hate to be told that something isn’t working in our novel, we do act on it if we come to feel it’s a valid point. And if we spy that fault ourselves we’re the first to throttle it and laughingly badmouth our error to the world. The revision of any given work can really go on indefinitely. All it takes is the willingness to improve. And I have to think that’s where we’re heading.

So which is it, new rising creative energy, or half-done work blindly flung into the World Publishing Machine? While it may be tempting to assume that the increasing quantity of eBooks means a corresponding decline in quality, consider that most writers really do want to keep improving. Although we hate to be told that something isn’t working in our novel, we do act on it if we come to feel it’s a valid point. And if we spy that fault ourselves we’re the first to throttle it and laughingly badmouth our error to the world. The revision of any given work can really go on indefinitely. All it takes is the willingness to improve. And I have to think that’s where we’re heading.

So … we are the recipients of numerous gifts. If we weren’t to get them until 2033, what would you being doing right now? Cranking more sheets through the typewriter, I hope!

copyright 2013 by Michael D. Smith