A Writing Biography, Part V: Space, Time, and Tania through The University of Mars, 1974-1982

It’s time I brought this series further up to date; ideas for it have been kicking around since 2014. Though it’s seemed unnatural to try to split my life up into these various parts, which I keep rearranging as I compose these posts, they do seem to form rational stages of my writing biography. Much of what Part V covers has already been the subject of various posts, to which I unhesitatingly link you during this psychic romp. So I don’t need to repeat myself, at least not that much.

Life Changes Amid “Space, Time, and Tania”

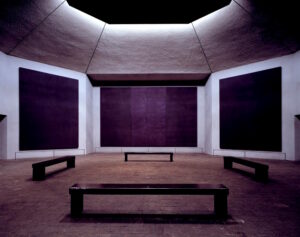

This is an essay about writing, not marriage, but standing as groom with bride Nancy in front of the three center paintings in the Rothko Chapel in Houston on August 17, 1974 marked quite a change. My Rice University college boy consciousness abruptly vanished. Undefinable happy/scary new life energies surged in its place.

This is an essay about writing, not marriage, but standing as groom with bride Nancy in front of the three center paintings in the Rothko Chapel in Houston on August 17, 1974 marked quite a change. My Rice University college boy consciousness abruptly vanished. Undefinable happy/scary new life energies surged in its place.

As related in Part IV’s summary of summer 1974 after graduating from Rice: our marriage plans, a public health library job in Houston, a new motorcycle, Patty Hearst on the run, the Lester Quartz comic strip, Watergate’s finale and Nixon’s resignation. I wrote the first parts of a breakthrough story, “Space, Time and Tania,” then completed it in Dallas a few days after Nancy and I got married.

As I brought home sustainable amounts of bacon from my downtown Dallas insurance accounting clerk job (expertly lampooned in my novel Zarreich; see below), I was determined to press my writing career despite new marriage/new city/new job/new psychic nutrient/new mind scatter, as exemplified by the stream-of-consciousness poems I typed at the office on adding machine tape and then affixed in my journal. But bits of this nonsense did become fodder for Akard Drearstone song lyrics.

Like most of the stories I wrote during this period, “Space, Time, and Tania” was lengthy at 14,300 words, and though I always referred to these pieces as stories, I now see they can be classified as novelettes (word count ca. 7,500-19,000). I hadn’t been aware of that designation until recently, and it may account for the many rejections of these longer pieces from short story magazines. These lengths also show how eager I was to abandon story writing and move into the expansiveness of the novel.

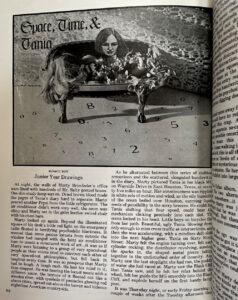

So bumbling ex-Texas Department of Public Death officer Marty Brimfeeler probes the death of Tania in Houston shortly before World War III erupts. Marty is traumatized by finding the body along with Tania’s cryptic notebook full of edgy metaphysical queries. He finds himself unable to cope with his state trooper work and equally unable to understand the notebook which has unhinged him.

“Tania” was a fun, intelligent, loopy story, despite being inspired by the kidnapping of Patty Hearst and her brainwashing by the Symbionese Liberation Army in 1974. The story strikes me now, as close to an impartial view after all these decades as I’m about to get, as properly channeling the universe. There doesn’t seem to be a career-minded ego trip to it. Of course it’s not really about Patty Hearst.

I finished Draft 2 of “Tania” a week before the idea for Akard Drearstone hit me, and was typing the story’s MS. as I geared up on Akard ideas–coincidentally, about the time Patty Hearst was captured in September 1975. “Neutral mindglow” and “the car dawn,” Akard song titles, were phrases used in “Tania.”

finished Draft 2 of “Tania” a week before the idea for Akard Drearstone hit me, and was typing the story’s MS. as I geared up on Akard ideas–coincidentally, about the time Patty Hearst was captured in September 1975. “Neutral mindglow” and “the car dawn,” Akard song titles, were phrases used in “Tania.”

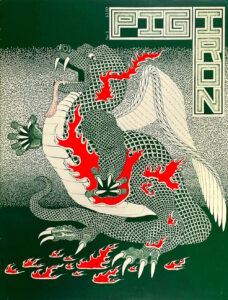

I sent the story on its few rounds to magazine publishers and was surprised and elated when Nancy called me at work in 1976 to read me PigIron magazine’s acceptance letter.

The story came out the following August, but suddenly I was wary and nervous. I didn’t know how to react to being published. I was also irritated at some obvious space-filling additions and the changes to the ending’s wording. I did protest this to the editor, yet also in another brief letter I wrote for publication in a later edition of the magazine, my tone was a weird mixture of egotistic and fawning. The editor invited me to send another “masterpiece,” but I said I didn’t have anything to send. I actually did have “The 66,000 MPH Bicycle,” but I guess I must have felt it too precious to expose to editorial mangling–sheesh! But more importantly, I told the editor that all my energies were now going to a monster novel.

You’d think my stint as editor of the Wiess Crack would’ve made me more sympathetic to the editor and to the difficulties of getting a magazine assembled and published. But at the time I was conditioned to think of editors as gods to be served or fought. But the exchange prompted me to acknowledge that I was now a novelist, no longer a story writer.

You’d think my stint as editor of the Wiess Crack would’ve made me more sympathetic to the editor and to the difficulties of getting a magazine assembled and published. But at the time I was conditioned to think of editors as gods to be served or fought. But the exchange prompted me to acknowledge that I was now a novelist, no longer a story writer.

My wariness also had to do with the eerie sense I had geographical isolation from my former life in the North and East. I didn’t feel I could relate to PigIron’s Youngstown, Ohio, for instance–even though this attitude was coming from a former Chicago north shore resident. But there was no email and World Wide Web; long-distance calls cost a lot of money; you didn’t just pick up the phone. And most of my old northern friends just didn’t write letters. For me, living in a different section of the country meant living in a different world.

In any case, claiming to be offended by the edits destroyed any possibility of real interaction. I’d had a publishing toehold and spurned it. It’s not wrong to hold your swing and check the pitches, but in retrospect my action was inexcusable. I could’ve published more in PigIron and still held my integrity. (See also an alternate universe in which I did send a masterpiece there.) But between my ego and the rush of Akard, my first story-writing/publishing-seeking cycle evaporated. I tried to resurrect it again in the mid-eighties, but soon saw it was just career-minded BS that went nowhere.

Why did it take me until 2011 to publish anything else? Await “Part VI of A Writing Biography” where I’ll take a crack at the Ambition Crash.

Some stories (or novelettes) during this period, most submitted to magazines:

In “Alan Ice on Morningcide Drive,” 1974 and 10,300 words, guitarist Alan Ice bores the reader with excessively overwrought stream-of-consciousness prose for thirty pages, but there’s a glimmer of interest when near the end he drives onto an infinite parking lot at dawn to watch an alien spaceship explode. This was my last truly incoherent story, because, near the end of typing its MS., I began paying attention to the concept of rewriting, and saw it might even be possible to actually get something sane across to a reader.

“Man Against the Horses!” 1975, 12,600 words, manages to express my new antipathy toward the city of Dallas and a bleak, regimented work schedule that felt like a return to high school compared to my insular, satisfied college student life in Houston. In this story five horses in Paris, Texas have finally had enough. They break out of their corral, charge down the highway, and, imbued with fresh superpowers, tear the city of Dallas to pieces.

“The Highland Park Cadillac Races,” 1975, 18,500 words, continues this vengeful satire of my new city as it showcases how insurance executive Bobby Thompson proves his manhood by racing Cadillac against Cadillac on the mean streets of Dallas.

“The 66,000 MPH Bicycle,” 1975 and 9,300 words, gestated from Rice-era musings while riding my bicycle at night. Here special agent Atoka evades “the Americans” on his nuclear-powered, 66,000 mph bicycle until he’s bombed into chewed-up guts on a coastal freeway. The author was able to ignore physics such as escape velocity throughout the story but came up with some interesting computer concepts for a story written in 1975 by someone who knew nothing about computers. I was chagrined to see this one rejected by PigIron long after I’d refused to send them a follow-up to “Space, Time, and Tania.”

Early Graphic Novels

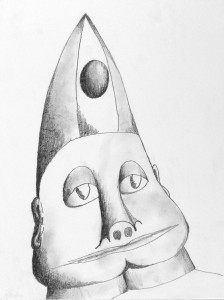

For some reason visual art benefited tremendously from early marriage’s delightful scattered consciousness. Over the summer of 1974 I’d drawn a few panels of The Story of Lester Quartz’s Fantastic Journey, Volume l, but I drew the bulk in my office at work that fall. At the time I called it a comic book, but it’s a true graphic novel, 288 panels in an 8 1/2” x 11” art journal, one panel per page, and becomes a sort of psychedelic Bildungsroman about a youngster who finds himself physically inside the city of another person’s brain. Riding buses, motorcycles, and trains to various adventures in that person’s brain, he falls in with urban terrorists trying to destroy the entire mind, and he finally takes control of the mind to, in the outer body, become a rock star–the first appearance of guitarist/songwriter Akard Drearstone. There are further nods to Patty Hearst and the SLA, as well as lucid depictions of the horrors of 1974 downtown Dallas.

For some reason visual art benefited tremendously from early marriage’s delightful scattered consciousness. Over the summer of 1974 I’d drawn a few panels of The Story of Lester Quartz’s Fantastic Journey, Volume l, but I drew the bulk in my office at work that fall. At the time I called it a comic book, but it’s a true graphic novel, 288 panels in an 8 1/2” x 11” art journal, one panel per page, and becomes a sort of psychedelic Bildungsroman about a youngster who finds himself physically inside the city of another person’s brain. Riding buses, motorcycles, and trains to various adventures in that person’s brain, he falls in with urban terrorists trying to destroy the entire mind, and he finally takes control of the mind to, in the outer body, become a rock star–the first appearance of guitarist/songwriter Akard Drearstone. There are further nods to Patty Hearst and the SLA, as well as lucid depictions of the horrors of 1974 downtown Dallas.

I colorized the journal with watercolor, crayon, and tempera through mid-1976, and also tried a couple other graphic novel exercises during this era, 1977’s Acid Loses Nothing! and 1977’s Art Journal #8 zigzagging between drawing experiments and book-length comic strip.

Akard Drearstone, 1978-1981

I often feel that certain stories are heralds of upcoming novels, either due to similar content or from an obvious yearning for more growth. In both these ways “The 66,000 MPH Bicycle” was the herald of the heady experience of a twenty-three-year-old composing the massive Akard Drearstone. The idea for the novel hit me all at once at my accounting desk at the insurance company one afternoon in August 1975. I quickly typed up a two-page synopsis that remained reasonably consistent with the final result, though I didn’t foresee typing 1,587 pages from that. After two years on Draft 1, two on a somewhat shorter Draft 2 along with reworking numerous individual chapters, I had a final version ready to type in October 1980. An Archeological Excavation of Akard Drearstone, Draft 1 goes into much more detail on this, and What Does Your Muse Think of Your Writing Career? ponders how my life would’ve been ruined if this immense project had somehow gotten published and, in modern terms, “gone viral.”

Akard Draft 1 was a vehicle for writing out years of adolescent Sturm und Drang as well as my entire Rice experience. It was my first true novel after two practice ones. I’ve always considered that this rough draft contains one good novel, one failed novel, and three mediocre novels. I believe I got the good one out in 2017’s final version.

But the first draft was such a powerful, life-changing experience that years later I scanned it into a 5 MB Word document just to have a copy, as for some reason I’d never thought to make a carbon as I typed the first two drafts. Those 1,587 typewritten pages, typo-ridden as they may be, come out to 661,581 words, 2,298 Word pages. I also designed covers for a four-part print experiment.

In this first version of the novel, barely congruent with 2017’s final edition, Akard Drearstone is a rising star in 1977, but he wrecks his fifteen minutes of fame on the Johnny Carson show and languishes as a bank clerk in Houston for two years until the spring of 1979, when he meets Jim Piston, troubled genius bass guitarist. Their collaboration rekindles his old fame and Akard sets up a music commune in a rural area north of Austin, adding a keyboardist and drummer. The four musicians battle corrupt businessmen, freak on psychedelics, get busted by mysterious narc agencies, stage demented concerts on the beach and at the scene of a car accident, debate the merits of a new philosophy called Exponentialism with a writer for a Sunday rotogravure magazine, postpone work on their album in favor of a three-month-long videotape, and insert self-serving mini-novels into the narrative. Their psychotic break-up leads to conflicts with national repercussions.

The second draft cut through much of the above BS. It was still an ungainly beast, but I developed new writing technologies for strengthening future novels. I began typing a manuscript to submit to publishers, but in August 1981 I’d aborted the effort at 377 pages. I’d finally outgrown this thing, had new writing to explore, and didn’t have the heart to finish typing out the last thousand pages just to complete a project.

Though I’d backed off short stories, a couple miscellaneous works surfaced during Akard:

“Tollhouse,” 1980, 19,100 words, came from a dream from years before. Two boys are trapped at a surreal tollbooth job in Australia, later emigrate to America, and then are killed at an anti-nuclear protest. But somehow one of them winds up in a hospital on Mars. Or he is just hallucinating that as he dies? Decades later the story morphed into “Randy and Laura,” published 2021 in The Damage Patrol Quartet. When I reread the original story a few years back I was struck by the character of Martian physician Draka Sortie and knew I had to use him for the Jack Commer series.

Another very short work came from a dream, 1980’s “Summer Burning City,” and posits a kid mainframe programmer on the top floor of a computing center who gradually realizes that the entire city is burning around him.

The University of Mars Draft 1, 1980 to 1981 Abandonment

Nineteen-year-old Bill longs to escape to an imaginary, mythic university he calls the University of Mars, intended to nurture the best of human culture as well as provide Bill sanctuary from the decaying human society of 2009, by which time the world is governed by a stagnant Christian bureaucracy. Bill begins to experiment with the hallucinatory consciousness brought about by contact with alien Transcendatrons who’ve quarantined the earth to stifle the evolution of a dangerous humanity. But the aliens possess an inherent psychological flaw and they’re as desperate for a solution to their problem as Bill is to evolve.

Nineteen-year-old Bill longs to escape to an imaginary, mythic university he calls the University of Mars, intended to nurture the best of human culture as well as provide Bill sanctuary from the decaying human society of 2009, by which time the world is governed by a stagnant Christian bureaucracy. Bill begins to experiment with the hallucinatory consciousness brought about by contact with alien Transcendatrons who’ve quarantined the earth to stifle the evolution of a dangerous humanity. But the aliens possess an inherent psychological flaw and they’re as desperate for a solution to their problem as Bill is to evolve.

Even as I readied Akard Drearstone for publication queries, I had an idea for a completely different book, a novel of ideas with science fiction elements. But it was hard to break my attachment to Akard; I felt I was being unfaithful to the previous work. As a matter of fact, even writing “Tollhouse” felt like trespassing on Akard’s territory.

Draft 1 of The University of Mars, 104,200 words, arose fitfully amid several life themes:

- In late 1979 I read The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich and also ran across the scarcely believable book Rocket Fighter by Mano Ziegler, a German Me-163 rocket fighter pilot. I began thinking about the further evolution of humanity as filtered through the prism of World War II, the mindless evil and the all-or-nothing struggle to eradicate it, as well as the often-murky origins of rocketry and space travel.

- I was trying to create nurturing life structures: taking the GRE, considering a master of fine arts degree, abandoning that to think about a creative writing degree, abandoning that, looking for new jobs, and finally, looking to a library career.

- The idea of a University of Mind had percolated for several years: an institution of thought and soul representing civilization in its highest sense, and coincidentally offering me escape from the hated insurance accounting job. (It’s also amusing that it wasn’t until 2015’s The Soul Institute that I finally nailed down this university.)

- Despite my paranoia about the March 1979 nuclear accident at Three Mile Island, I eventually realized I wasn’t opposed to legitimate uses of technology, and that technology is an indispensable human endeavor.

- I’d already written the chapters “The Flying Saucer Novelist” and “Don and the Boys,” both about terrifying encounters with aliens, without knowing much about the alien visitation literature. Then I picked up The Andreasson Affair and it horrified me as much as The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich had the year before. I read more and more extraterrestrial contact books, fascinated and appalled. And so alien Transcendatrons hijacked my manuscript.

But I saw to my chagrin that my novel of ideas was sliding into silly science fiction games. Trying to inject some passion, I launched a Part II incorporating an old idea of incorporating every single detail of the second semester of my sophomore year at Rice–a project doomed to quick and abysmal failure.

I also glued a 1980 story, “Where Eagles Have Unfortunately Landed,” 12,600 words, into The University of Mars until I sensibly cut this jokey account of how child genius Klaus Wolfgang von Stuttelmann fails to become a Messerschmitt-163 rocket ace for the Luftwaffe.

As you can imagine, Draft 1 never came together. See also The University of Mars blog post for further reasons. But the first draft had some noble aspects and it forced me to pull my nose out of Akard Drearstone, to see there was much more to write about than rock group counterculture.

I left this novel in the state known as “sprawling mess” so I could work on a new book.

Zarreich, 1981-82

After years of barely holding my own against my hated insurance job, I finally found fun employment at Dallas Public Library, where I began a library career that eventually came to function as a convenient exoskeleton for my writing/art life. Huge new energies arose in the spring of 1981 and soon I was working on an ambitious psychological novel that went far beyond my first four novelistic ventures. This dream was the seed for Zarreich’s 146,300 words:

After years of barely holding my own against my hated insurance job, I finally found fun employment at Dallas Public Library, where I began a library career that eventually came to function as a convenient exoskeleton for my writing/art life. Huge new energies arose in the spring of 1981 and soon I was working on an ambitious psychological novel that went far beyond my first four novelistic ventures. This dream was the seed for Zarreich’s 146,300 words:

The village in the sunny valley (arranged as: plain, valley, hill, 2nd plain–the first valley is the quaint village–the 2nd plain is the magnificent city built out of nothing.) Into this I come, a Jim Piston character with my .38. [Jim being the sociopathic bass player in Akard Drearstone.] I live in the first valley with my grandmother. But a guy next door strikes me as evil and so I shoot him–several times–but though I know I am doing damage he keeps standing in the doorway laughing. In paranoia I keep loading my gun and firing at this guy. In the kitchen. Finally I say to myself: “C’mon, you’re acting just like Jim Piston now.”

Thus an adolescent comes to live in a small town with his grandmother, only to discover all his memories have been wiped. He panics and commits a murder, then finds himself a member of a secret commune remembered only in dreams.

My nightmare city of Zarreich had been kicking around in dreams for years. I typed out exactly one hundred of the more surreal dreams I’d recorded over the previous decade, dreams pointing to what seemed to be a valid alternate world. Integrating these dreams into the novel–something like twenty-two made it in–was a severe challenge to organizing a plot.

Zarreich only made it through a first draft. I later tried a revision called The Galaxies Groan Within, but all that book did was cut the original novel in half and trivialize its extremely disordered forces. I rejected that second draft and now consider the first one to be the real, albeit unpublishable, novel. Much more on this novel in the Zarreich blog post.

A few stories during this time explored similar new forces:

“Zorexians,” 1982, 23,302 words, composed during Zarreich and somewhat complementing it, plunks my childhood spacepilot Jack Commer into a detective agency foursome that discovers that alien masterminds have subverted the United System Space Force and indeed, all of humanity. Everyone is terrified when Jack’s partner Huey is revealed to be an alien himself, but soon mystical interspecies communication takes place. Later Jack is interviewed by the author about his feelings for Huey’s sexy wife Jackie. I tried to port this to early versions of Nonprofit Chronowar but though this story was part of the inspiration for NPC, it never fit. I did include the interview in The UR Jack Commer.

In the two-page “The Selector,” 1982, strange, supercilious animals chew out the electrical grid of a downtown skyscraper. Apparently they’re eating the entire building, but a night shift supervisor is in extreme denial about the entire affair. This came from a dream and it works well enough to have been posted to blog.sortmind.com.

Another short piece from a dream, 1982’s “Caretaker” follows a similar night watchman who unthinkingly samples some of the cactus from a university’s extensive peyote planters. Soon he hears an ominous and unexpected visitor tromping down the concrete stairs to his basement caretaker lair.

In November 1982 I had great fun banging out “Six Plots,” short musings intended for a graphic novel I only got a few pages through. But they included a Jack Commer scenario and the earliest ideas for Sortmind, in a way forecasting much different writing ahead in Part VI.

And, odd to say, one Zarreich chapter was published after all, revised and finding standalone expression in the story “The Roadblock,” which I published in The Damage Patrol Quartet, 2021.

Back to The University of Mars: Draft 2 Breaks the Censor

Zarreich’s major contribution to my writing career was breaking the internal censor; I quickly found myself crashing through scenarios that broke all my previous taboos. Even the obscene rock-and-roll world of Akard Drearstone failed to record anything real about male-female relationships. My writing hadn’t been grown-up; Akard and the first version of The University of Mars often aimed at serious issues but quickly veered into irony and cynicism.

Finishing the rich but disordered Zarreich opened the way to rewrite The University of Mars into a real novel. I permitted Bill to ponder his feelings for Karen and grapple with their separation, I had my first practice writing from the female character’s point of view, and I saw a way to deepen Karen’s character in an emotionally satisfying ending. The final chapter was a triumph, though it was naïve of me to expect anyone to wade through three hundred pages to get there.

I truly struggled to create a good and satisfying ending to this book; in fact this was the first of my five novels to arrive at one. I guess The University of Mars showed me how this could actually be done.

It felt great that, after years of struggle, such a good-hearted book emerged in its second draft. Eleven people read the photocopy, laughing in the right places and generally complimenting the work, and I was ready to type up a fresh MS. and send it to publishers.

copyright 2023 by Michael D. Smith

A Writing Biography, Part I: First Efforts in The Gore Book

A Writing Biography, Part II: The Blue Notebook

A Writing Biography, Part III: Unhappy Kid Interlude, Yet Two Novels, Sort Of

A Writing Biography, Part IV: The Perfect Cube and Beyond

Other URLs mentioned:

Homage to the Wiess Cracks

What Does Your Muse Think of Your Writing Career?

An Archeological Excavation of Akard Drearstone, Draft 1

Akard Drearstone

The Damage Patrol Quartet

The Soul Institute

Homage Part 1: Farewell to The University of Mars

The Exoskeleton

Homage Part 2: The Zarreich Enigma

Nonprofit Chronowar

The UR Jack Commer

The Selector

Sortmind

Symbionese Liberation Army (Wikipedia)

Rothko Chapel

Pingback:A Writing Biography, Part VI: Failures, Successes, Rhythms and Swerves, 1983-1994 – Sortmind Blog – Michael D. Smith

Pingback:A Writing Biography, Part VIII: The Exoskeleton, Archiving, Publishing, The Blog, and the Long Novels, 2011-2023 – Sortmind Blog – Michael D. Smith