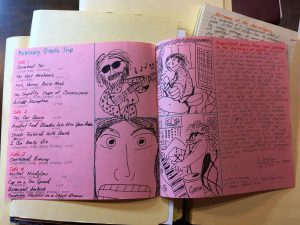

A few years ago I resurrected my first attempt at a novel, Trip to Mars, fifty-five penciled pages in a small yellow notebook with numerous crude illustrations. The 2,646-word story I produced as a sixth grader in the spring of 1964 is childish, cute, and illogical, but when the urge struck me in 2013 to render it into a children’s picture book, a wondrous psychic bridge somehow formed between child and adult, a union I really hadn’t expected. The modern illustrations peer through the childhood lens of 1964 but amplify and transcend the kid story, and this project became an homage to the writing it later inspired.

A few years ago I resurrected my first attempt at a novel, Trip to Mars, fifty-five penciled pages in a small yellow notebook with numerous crude illustrations. The 2,646-word story I produced as a sixth grader in the spring of 1964 is childish, cute, and illogical, but when the urge struck me in 2013 to render it into a children’s picture book, a wondrous psychic bridge somehow formed between child and adult, a union I really hadn’t expected. The modern illustrations peer through the childhood lens of 1964 but amplify and transcend the kid story, and this project became an homage to the writing it later inspired.

To make the picture book, I expanded the twenty-page manuscript into sixty-five pages of a few lines each, then illustrated each page in pencil. I decided the entire book would be black and white, and used a finger-rubbing technique to make numerous grayscale gradients. The book’s first version in March 2014 was the scanned Word document saved as a PDF, then turned into a Windows Media Video file, and finally posted to YouTube. But I’d always wanted a physical picture book paperback, and after much experimentation completed the project in March 2017. It’s now available as a compact and perfectly-sized 9″ x 7″ landscape-format paperback on lulu.com. I may do an eBook later but the paperback now satisfies my needs.

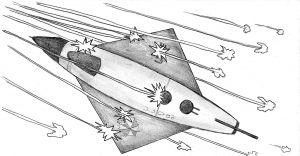

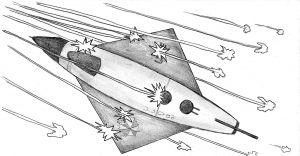

The story outlines the horrors of World War IV in, at that time, the extremely far future of 2033, along with the discovery of the moon’s instability and the resulting evacuation of the planet’s surviving population to Mars. Jack Commer, hero of my later published science fiction series, pilots the nuclear-powered spaceship Typhoon I and leads the same eight-man crew he’ll captain in The Martian Marauders, Book One of the Jack Commer, Supreme Commander series. The crew includes Jack’s three brothers Joe, Jim, and John. I think I originally named the four brothers after four identical plastic spacemen I had in elementary school. I recall that one of these four spacemen was a little lopsided and he thus became the somewhat loopy John Commer, the youngest brother who later makes a disastrous mistake with the Typhoon I in The Martian Marauders.

The story outlines the horrors of World War IV in, at that time, the extremely far future of 2033, along with the discovery of the moon’s instability and the resulting evacuation of the planet’s surviving population to Mars. Jack Commer, hero of my later published science fiction series, pilots the nuclear-powered spaceship Typhoon I and leads the same eight-man crew he’ll captain in The Martian Marauders, Book One of the Jack Commer, Supreme Commander series. The crew includes Jack’s three brothers Joe, Jim, and John. I think I originally named the four brothers after four identical plastic spacemen I had in elementary school. I recall that one of these four spacemen was a little lopsided and he thus became the somewhat loopy John Commer, the youngest brother who later makes a disastrous mistake with the Typhoon I in The Martian Marauders.

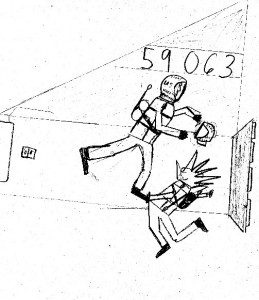

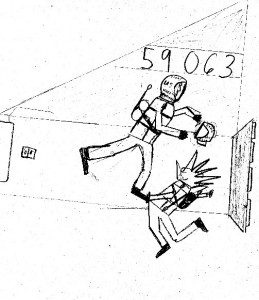

Trip to Mars is the 1964 kid’s view of space exploration, tempered by nuclear war fears and a feeling of growing societal disruption; in fact, the story includes a senseless Kennedy-like assassination, still fresh in my mind from the previous November. As a childhood prequel to my Jack Commer series, Trip to Mars also contains themes explored in the later books. Many of the story’s details are taken up in 2012’s The Martian Marauders and some, like the passenger shell catastrophes that numbed the second oldest brother Joe, find expression in 2013’s Nonprofit Chronowar.

Trip to Mars is the 1964 kid’s view of space exploration, tempered by nuclear war fears and a feeling of growing societal disruption; in fact, the story includes a senseless Kennedy-like assassination, still fresh in my mind from the previous November. As a childhood prequel to my Jack Commer series, Trip to Mars also contains themes explored in the later books. Many of the story’s details are taken up in 2012’s The Martian Marauders and some, like the passenger shell catastrophes that numbed the second oldest brother Joe, find expression in 2013’s Nonprofit Chronowar.

The modern Trip to Mars follows the text of the 1964 notebook with only spelling corrections; for instance, I’d misspelled the ship’s name “Typoon” throughout. Awkward phrasings and illogical plot developments are just allowed to do their thing, buoyed up by hopefully funny new illustrations. Of course I could have rewritten the story to modern adult standards, but the effect of naïve writing juxtaposed with modern illustrations is the whole point of the book.

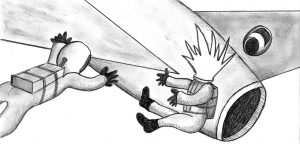

I used some of the notebook’s juvenile drawings for new image ideas, but also had much fun drawing concepts the sixth grader knew nothing about. One panel shows a scientist pointing to equations from Einstein’s 1905 Special Theory of Relativity. Another copies the astronomer Schiaparelli’s 1886 drawing of Martian “canals.” Another is an homage to the cover of Heinlein’s Have Space Suit–Will Travel. I also depict a Marsport Automated Transport System bus, which later becomes a flippant robotic character in The Martian Marauders and subsequent books.

I used some of the notebook’s juvenile drawings for new image ideas, but also had much fun drawing concepts the sixth grader knew nothing about. One panel shows a scientist pointing to equations from Einstein’s 1905 Special Theory of Relativity. Another copies the astronomer Schiaparelli’s 1886 drawing of Martian “canals.” Another is an homage to the cover of Heinlein’s Have Space Suit–Will Travel. I also depict a Marsport Automated Transport System bus, which later becomes a flippant robotic character in The Martian Marauders and subsequent books.

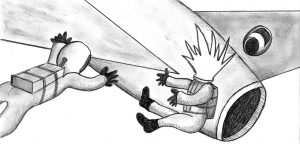

A 1964 loose space helmet

A modern loose space helmet

While the exterior views of the Typhoon are consistent, being more or less the same ship I drew hundreds of times as a child, the interior views are a series of theater stages that can’t be reconciled with the layout of an actual ship about the size of a space shuttle. I immensely enjoyed drawing these interiors that just cannot be.

copyright 2017 by Michael D. Smith

Trip to Mars available at lulu.com

Early marketing efforts for Trip to Mars

2014 YouTube video

Background at sortmind.com and links to current Jack Commer titles

The back cover:

Writers know how difficult it can be to come up with a decent book blurb. How can we possibly distill our novel’s entire universe into one attention-grabbing slab of marketingese? The good news is that now you can just blow all that off and concentrate on getting that next novel underway. Just change the character and place names in your story to match the blurbs below–and watch your sales surge out of control!

Writers know how difficult it can be to come up with a decent book blurb. How can we possibly distill our novel’s entire universe into one attention-grabbing slab of marketingese? The good news is that now you can just blow all that off and concentrate on getting that next novel underway. Just change the character and place names in your story to match the blurbs below–and watch your sales surge out of control!