Being overly busy and overly inclined to slap projects together and ship them out the door, declaring victory after victory, I have not been much inclined to slow down to zero and come to grips with my crisis in abstract painting.

Being overly busy and overly inclined to slap projects together and ship them out the door, declaring victory after victory, I have not been much inclined to slow down to zero and come to grips with my crisis in abstract painting.

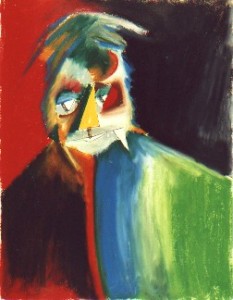

I’m not faulting abstract painting itself. I’ve seen many powerful examples of abstract and I know that there can be numinous power in them–raw power speaking to existence itself. And while some abstract works may just be pretty designs and lack any such power, what other artists do doesn’t concern me much now. I’m really just looking to explore my own relation to abstract art.

Not only because I’ve seen great abstract art, and done abstracts myself that I feel have had real meaning, but also because I know other abstract artists with talent and sincere motivation, I wonder how to express my own new misgivings respectfully. I want to be measured and fair, but I’m also aware that much of what I say about my own relation to abstract art applies to other abstract artists as well.

Is abstract art just pretty design? Have I come to the end of what I was supposed to do with it? Is there any real audience for abstract art–much less a “market”? And why should I desire such a market?

Is it all overblown posturing? Something fairly easy to churn out, even with the various aesthetic crises arising during any given painting? Is it all overpriced? Is talking about “abstract meaning” just a copout? Is it a matter of seeing what you can get away with? As opposed to novels, which imply a reader able and willing to follow the unfolding of a real story?

Is the purpose of abstract art to give the artist a career? One that really doesn’t require too much effort? How much loving care and search for real meaning goes into “an afternoon’s work worth $5,000?” Is abstract art a vehicle for hiding your emotions? Keeping it cool? Who is fooling whom? Has it all been done before?

Is it possible to articulate anything real about abstract art? Stripped of fashionable jargon and meaningless artsy BS? Can the abstracts go back to having an emotional, psychological function, and cease trying to lazily hint at some diffuse metaphysical gesture?

The amount of energy I’ve devoted to writing these past few years has made thinking about art harder. I want a new visual expression, but aside from a feeling of weariness about recent trends in my own art, I’ve been drawing a blank about the next step. Maybe there IS no next step–which also gives me pause.

In 2011 I finally realized a longstanding ambition to make giant mural-sized canvases, and wound up with four unstretched canvases that I hung at the Renner Frankford Library in August. The final installation looked good, and I got a lot of good feedback from those who actually saw the hung paintings, as opposed to the digital images on sortmind.com.

But executing the paintings was mostly unsatisfying. The first one may have been all I needed to do. The use of unstretched canvas may have a venerable history, but I disliked the process of shoving paint onto the loose wrinkly surface, then struggling to pin the finished product vertically so I could see and evaluate it. The second painting was OK, but was even more rushed than the first. The third painting, the five foot by fifteen foot monster that I immediately knew was crap and then cut into two paintings, both overpainted into much better works, showed my limits: exhaustion, trying to conserve paint (these supplies get expensive!), simply “completing the assignment,” and, running through all the paintings, trying to quickly blast something out and hope that size alone will convey some monumental impact.

But executing the paintings was mostly unsatisfying. The first one may have been all I needed to do. The use of unstretched canvas may have a venerable history, but I disliked the process of shoving paint onto the loose wrinkly surface, then struggling to pin the finished product vertically so I could see and evaluate it. The second painting was OK, but was even more rushed than the first. The third painting, the five foot by fifteen foot monster that I immediately knew was crap and then cut into two paintings, both overpainted into much better works, showed my limits: exhaustion, trying to conserve paint (these supplies get expensive!), simply “completing the assignment,” and, running through all the paintings, trying to quickly blast something out and hope that size alone will convey some monumental impact.

There was merit in at last exploring the idea of being an abstract mural painter. I saw that I really was not up to the task, and didn’t have any clear conception of what to do with such a huge space. Nor was the desire to learn and expand with this project really there. So I really didn’t want to do extremely large abstracts after all!

In the 90’s I embraced the idea of a “metaphysical” abstract meaning, and my 90’s abstracts, many of them large at five by five or five by six feet, were sincere explorations. Then came the idea (boneheaded in retrospect, but it seemed to flow easily at the time) that visual art would be my prime career energy, that I could make more selling one painting that was done in an afternoon than I could make from a novel I spent five years on. I began showing at open shows, then got library shows, good feedback, and a certain amount of recognition. And the paintings were good, there was nothing fraudulent about them. With the force of some good shows behind me, I naturally assumed, as did those around me, that my primary calling was visual art and that I would make my way as an abstract artist, pursuing that metaphysical meaning. This dovetailed with a scary decline of my writing energy, which I scarcely realized at the time.

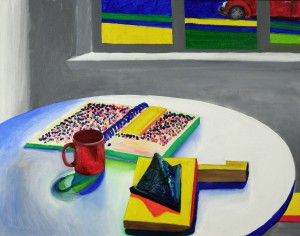

I went over this in the blog post My Visual Art is Somehow Literary. No need to repeat all of it here, but I can now more clearly see that the abstraction in my “career art” between 2000 and 2006 was a different mood, and while I still think highly of most of it and I advanced in technique and professionalism, learning how to hang shows, transport paintings, and sell art, a more and more purely mercenary mood started creeping in. While monetary concerns are certainly not evil and are part of part of any artist’ s life, I did begin seeing how a quick afternoon’s work might be called upon to pay a month’s mortgage. And how many afternoons did I have to spare, how much could I turn out in how much time? When I did hit a solid meaning abstract such as July 2007’s A Tour of Raw Architectural Space, I’d find myself repeating it, seeking mechanical ways to reconstitute that energy. The hassle and uncertainly inherent in those punishing day-long sessions is also a clue–the dreary cycle of getting into trouble with the painting and then desperation to redeem it. Then there was accepting less-than-quality work as somehow “that’s the way it turned out to be,” and only realizing much later how much I hated it.

I went over this in the blog post My Visual Art is Somehow Literary. No need to repeat all of it here, but I can now more clearly see that the abstraction in my “career art” between 2000 and 2006 was a different mood, and while I still think highly of most of it and I advanced in technique and professionalism, learning how to hang shows, transport paintings, and sell art, a more and more purely mercenary mood started creeping in. While monetary concerns are certainly not evil and are part of part of any artist’ s life, I did begin seeing how a quick afternoon’s work might be called upon to pay a month’s mortgage. And how many afternoons did I have to spare, how much could I turn out in how much time? When I did hit a solid meaning abstract such as July 2007’s A Tour of Raw Architectural Space, I’d find myself repeating it, seeking mechanical ways to reconstitute that energy. The hassle and uncertainly inherent in those punishing day-long sessions is also a clue–the dreary cycle of getting into trouble with the painting and then desperation to redeem it. Then there was accepting less-than-quality work as somehow “that’s the way it turned out to be,” and only realizing much later how much I hated it.

Where was the real psychological exploration?

I’m still proud of the abstract paintings I’ve done that do have power. I don’t feel that any of the works I’ve sold, abstracts or figurative, have been low quality–and I feel their prices have been justified. I definitely do not want to give the impression that I’ve been pulling the wool over the eyes of innocent buyers!

By 2011 Double Dragon Publishing had accepted The Martian Marauders and I’d been long aware that the real fun lay in writing. So all in all it’s been OK to let visual art slide over the past several months. I’ve done no paintings since last July.

But now I feel a vacuum: I remember the good side of the glorious painting energy–yet I now dread the energy drain hassle involved in setting aside a day to paint, I feel totally uncertain of what I might want to paint, I wonder if I even want to paint at all or do color pencil instead–and above all, the question of meaning comes in.

The meaning theme is the core of the entire abstract art crisis. Being overwhelmed by the Rothko Chapel in April 1973 was my initiation into the existence of true abstract power. But I basically have not felt much of it in my own work after 2000. Exposure to other abstract artists’ work, as well as the scads of art I’ve seen in contests and in the galleries I’ve visited, and in the hopeful gallery-opening postcards I get, have not gotten me confused about my own visual style, which is like my own handwriting. I’ve never worried about comparing my work to others’ except whenever I’ve pursued “career” in low energy.

But have I just been making pretty images of sixty watts of meaning when what I want is a novel’s entire nuclear reactor output? When I wrote in a blog entry to ask the question, Is Abstract Art More Difficult?, was I really saying that abstract is difficult because I’ve made it into a chore? With the result being some mysterious aesthetically balanced or correct image that passes muster enough to be sold to pay a month’s mortgage? (And face it, we are often asking for three month’s mortgage.) Have I raised the idea of “difficult” as being superior to having a blast doing something you love?

So I lost touch with “metaphysical” meaning to abstract art, and began to think of it as “good design” and even “easy work,” with paintings moving along a conveyor belt of bleary execution, the digital photo session, the long and admittedly fun creation of new web pages for the work, the email to the sortmind.com list, and hopefully a couple return emails saying “Cool.”

It should be obvious that all this is totally opposite my writing energy, where I enjoy every aspect of creating it, including the problems that come up, where my energy increases the more I do it, and where, when I send off queries or interact with my publisher, I feel confident and professional and in command of my art, knowing I can always learn more and keep growing.

It should be obvious that all this is totally opposite my writing energy, where I enjoy every aspect of creating it, including the problems that come up, where my energy increases the more I do it, and where, when I send off queries or interact with my publisher, I feel confident and professional and in command of my art, knowing I can always learn more and keep growing.

I don’t feel any of that about visual art right now. In fact, I hold my nose in disgust at the nonsense in almost every artist statement I’ve come across, at the corruption of speech about art, whether it’s in the media or from other artists. There is so much delusion and misdirection and plain verbal laziness at the bizarre intersection of academia, galleries, and art publishers. “My art explores the synergy of opposing diversities and postulates epicycles of awareness.” I feel I’m stepping into nightclubs where I don’t belong, being offered weird drugs and introduced to people-in-the-know who don’t really seem to know anything.

I will repeat that I do think it’s true that trying to pull together an abstract composition that makes emotional sense can be much more difficult than executing a drawing of roses in a vase and then coloring it in. Yet maybe that’s too simple after all: the difficult abstract might struggle to carry fifteen watts of meaning, and while the vase of roses might be simple to plan, as executed it may reveal deeper power–it might even be as numinous as the Rothko Chapel.

I’ve been hesitant to declare in manifesto style that abstract art is meaningless, because what if I do want to again pursue the abstract energy? What if I want to improvise again? I don’t want to limit my explorations by declaring what I will and won’t do. Likewise I don’t want to declare a return to realism. I know I’m a little out of shape for it, but I also know that I could quickly ramp it up if I desire. But I definitely don’t want to return to what I used to do with painting and realism, which was a kind of mechanical paint by numbers execution.

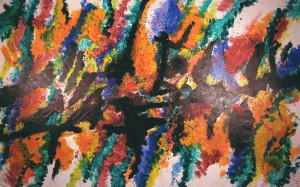

I think what I’m truly rebelling against is 2D improvisation, no matter how much I admire Franz Kline or Rothko. For me it’s become merely design and problem solving. The redeeming feature to me of 2D abstract is when it can nevertheless suggest vast emotional space. Instead it’s all too often a roiling mass of chaotic forces.

Just wanting an abstract painting to have meaning, and even giving it some metaphysical title, can’t impart that meaning to it. The best titles suggest an approach to the painting. They really can’t carry it, and in some cases the titles are so ridiculous that they degrade the actual physical image.

Changing from a metaphysical approach to a psychological one, in the same way I’ve geared up for psychological novels, may seem like a step down, but in doing the psychological I’m reengaging with what I can really touch as opposed to what increasingly looks like wishful thinking in the “metaphysical” realm.

The last few years of new honesty and deeper writing have set into motion whatever will be. I do feel a desire for some real images, and considerations of how they come about are really secondary now. I’ll just let it happen while paradoxically pushing it–as this writing is part of pushing it.

copyright 2012 by Michael D. Smith