I’m struck by the veering between successes and failures in this period, losing control and skidding across all four lanes until I’d finally get enough sense to stop the car and take a good look around. Had I never learned what works and what doesn’t? Had I long ago used up my beginner’s luck? Those marvelous fifth-grade stories? (A Writing Biography II) The Rice-era looseness? (A Writing Biography III) The gift of Akard? (A Writing Biography V)? From now on would I just dully navigate an overloaded cargo plane between commercial airports?

I lurched between faulty old works and bright new concepts even as I finished library graduate school and got too involved with that career. In fact this last theme, recently explored in The Exoskeleton, may account for much of the confusion of this period.

But somehow I was establishing new novel-writing rhythms.

The Crap of Galaxies

The Galaxies Groan Within dragged its sorry self across the spring of 1983, even as I congratulated myself as an efficient editor of my own writing. For this novel was the second draft of Zarreich, which, I remind the reader of previous Writing Biography posts, posits that:

An adolescent is sent to live in a small town with his grandmother, only to discover that all his memories have been wiped. He panics, commits a murder and saws up the body, then finds himself a member of a secret commune remembered only in dreams.

I cut the original novel by fifty percent. I combined repetitive rough draft characters, simplified the plot, and reconciled the absurd contradictions. But for all its faults Zarreich had explored much dangerous territory just for Galaxies to come down hard on it and banalize those disordered forces. Beta reader reaction to this effort was decidedly lackluster. It took me years to recognize that the first draft, Zarreich, was the valid if unpublishable novel.

The Vow from 1983

In the middle of funk about Galaxies and much work stress came a marvelous July nightmare that led to Awesome Beauty of This Earth. I later changed the overdone title to The Psychobeauty and it remains unpublished, but in the dream, ninety-seven percent of the earth’s population inexplicably commits suicide, ending civilization and leaving scattered refugees struggling against their own suicidal urges. I grabbed this novella like a life preserver; this was what I wanted writing to be: capable of many voices and moods, pinpointing characters, their morals, senses of life, dialogues, and interactions, without typical literary characterization crap, speaking with hammer force yet retaining the sense of the outrageous. What an amazing thing that was to write.

Another novella, The First Twenty Steps, came from a decade-old dream where I was part of a ruthless commune swooping from helicopters to attack a fifty-nine-story office building deep in the urban night. I’d always thought “59” unwritable. It was a buried dream, plotless, wordless, yet so powerful. Why were we attacking that building? In any case, in a comment on my current stress, the ex-convict is loosed onto the streets of the unknown city, confronting the Cathedral Spaceship that, locked away, he’s never seen before. Before long he finds himself mixed up in a motorcycle gang’s plan to heist a hyperspatial supercomputer.

Confidence returned with these novellas and a crisp story, “Damage Patrol.” I saw them all as publishable, but above all it was finally time to market a novel. Thus my first priority was the just-finished University of Mars. I now confronted the ordeal of typing a 320-page manuscript.

Typescripts, Queries, and the Ambition Crash

Still, my introspective, non-promotional self shrank from the scary world of publication, and tepidly engaged with literary careerism as I deludedly understood it. Follow the advice of the professionals, establish yourself in little literary magazines, build up publishing credits, tone yourself down, write safely, be on the make, know the right people.

So I dredged up past junk. “Roadblock” from Galaxies and “January 1st” from Akard were quickly pressed into service to call my exceptional talents to the attention of Big New York Publishers.

The University of Mars from 1980

Never mind any human’s potential for greatness, just get that shovel and follow me to the graveyard. But there’s a limited number of dead manuscripts, and they require a lot of Frankenstein work. You begin to get dependent on old writings. You cease to look to the future, not the so-called scary blank sheet of paper, but the scary 50,000 sheets you’re suddenly too weak to write.

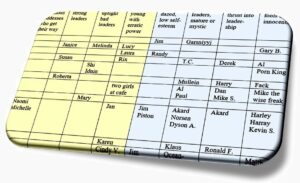

Some of the efforts from the Ambition Crash era, loosely 1984-1986, none published:

- “The Selector,” 1982-84, from a dream about animals chewing their way through downtown buildings, typed 1984 as story publication fodder.

- New Akard 1979, a 1984 rough assembling of 1981’s abandoned 310-page typescript plus most but not all of Akard Drearstone’s remaining Draft 2 chapters; this 853-page chunk served notice that I was done with Akard.

- Millicent Faustus, late 1983-early 1984. A graphic novel about an alchemical goddess, abandoned after a handful of pages, which made use of story ideas from 1982 that later influenced Sortmind.

- “Chapter 32,” 1985, a continuation of New Akard 1979, apparently not dead after all. Akard returns to creative power, Pete Sponge revives from a coma, and Jim Piston cries his eyes out upon realizing he’s an impotent monster.

- Oliver, 1984, an aborted experimental novel about future wars in the South Pacific and young men of the following generation, unable to appreciate what their fathers have accomplished; parts incorporated into early Sortmind.

- “January 1st,” 1976-1984, from Akard Drearstone. Anti-hero bass guitarist Jim Piston helps rob a 7-Eleven in Skokie, Illinois on New Year’s Day.

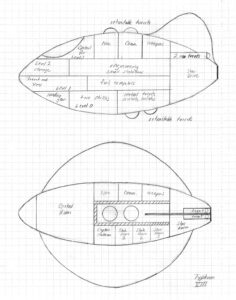

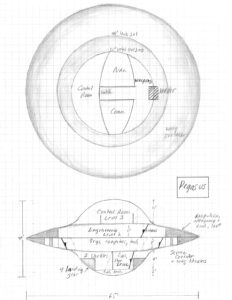

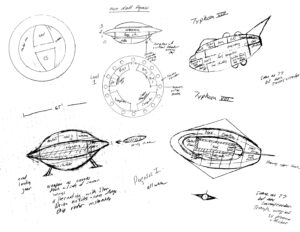

- The Adventures of Tree Leopard, 1985, a graphic novel; leopards build a flying saucer underneath the Municipal Ping Pong Stadium, kidnapping and reprogramming humans to act as their slave technicians.

I had four publishing query eras through 1995:

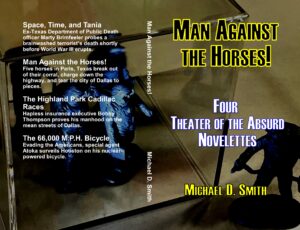

- 1975-ca. 1977, during which time my story “Space, Time and Tania” was published.

- 1980: Just one story, “Where Eagles Have Unfortunately Landed,” sent four times.

- 1984-86: The University of Mars along with stories intended to pave the way for its awesome typescript. This formed the core of the Ambition Crash.

- 1991-95: Sortmind and Property–a renewed attempt to publish; more below.

Here’s my calculation of submissions. Through 1995 I made about 176, all rejected except “Space, Time and Tania.”

- “Underground,” 1970, though it came back undeliverable; even the post office rejected my submission! Later published Spring 1971 in the Rice University Janus, but that was an easy student publication and doesn’t seem to count. A rejection slip dated 8/10/71 probably marks an attempt to submit it elsewhere.

- “The Martian Holes,” 1975, a flippant, word-wasting story, yet speaking to the Jack Commer myth. Sent twice.

- “The Wires of Consciousness,” crappy, meaningless 1975 story sent twice before I came to my senses.

- “The Highland Park Cadillac Races,” sent five times.

- “Space, Time, and Tania,” sent three or four times. Accepted August 1976 and published 1977 in PigIron magazine.

- “The 66,000 MPH Bicycle,” sent six times, five in the ’70s and to PigIron in 1984.

- “Where Eagles Have Unfortunately Landed,” sent four times between July and November 1980.

- The University of Mars, sent to twenty-three agents or publishers from 1984-1986; three of them were the entire novel. The last rejection was November 1986.

- “The Selector,” sent four times.

- “January 1st,” the only chapter from Akard ever submitted; sent seven times.

- “The Roadblock,” a chapter from Zarreich/Galaxies, sent five times including to PigIron.

- “Damage Patrol,” sent four times.

- Awesome Beauty of This Earth, sent six times.

- The First Twenty Steps, sent four times between December 1994 and March 1995. Revised 1996 for a publishing venture that didn’t work out.

- Sortmind, sent to thirteen publishers or agents, including the entire MS. one time, from August 1991 to November 1994, with final rejection 3/31/95.

- Property, sent to thirty-eight publishers or agents, including the entire MS. three times, January 1992 to August 1993, with final rejection 8/16/93.

It was The University of Mars, my flagship novel in this period, that crashed my 1980s ambition. Daring to rewrite this book’s self-indulgent and confused first draft had taken some courage, so when I finally had a real and publishable novel in hand I began typing its manuscript in high optimism. Certainly there was room for improvement, and I figured I’d gladly negotiate changes with a publisher. The book had real heart; what I never realized was that the heart only shows up toward the end of 320 typed pages. Can you really expect anybody to wade through all that?

It was The University of Mars, my flagship novel in this period, that crashed my 1980s ambition. Daring to rewrite this book’s self-indulgent and confused first draft had taken some courage, so when I finally had a real and publishable novel in hand I began typing its manuscript in high optimism. Certainly there was room for improvement, and I figured I’d gladly negotiate changes with a publisher. The book had real heart; what I never realized was that the heart only shows up toward the end of 320 typed pages. Can you really expect anybody to wade through all that?

Typing the MS. was an awesome obstacle in itself. From my blog post, Homage Part 1: Farewell to The University of Mars:

It’s much more final than a computer printout. You’re setting concepts in paper stone as you mortgage months of your writing time. A mistake or a revision of a couple words can involve twenty minutes of retyping an entire page. A major revision of the first chapter throws off the pagination of the entire manuscript! Retype, or messily fudge it with “continued on page 35”? And when you’re done with the unspeakable ordeal of hacking out hundreds of pages, but make the mistake of rereading Chapter Six and finding yourself dissatisfied with some verbiage, you simply … try to ignore the problem …

I was hazily aware that screw-ups could be instantly corrected on one of the new-fangled word processors, but I didn’t own a computer and had no idea how to use one. So I typed 320 pages of The University of Mars on my 1940s manual Royal typewriter. Yet over the next couple years, as I sent out query letters and battered photocopies of sample chapters and collected my rejections, I grew more and more aware of the novel’s flaws. The $45 agent just confirmed what I’d already suspected.

I finished the exhausting typing by August ’84, but then was scared to send it anywhere. Meanwhile Awesome Beauty came back a few times and I began to suspect its 32,000 words were too long for a publishable story. I finally got a query letter and sample chapters of The University of Mars off to Doubleday, then steadily pushed out more queries. But I was pessimistic, dispirited, and dry for any new writing. Gifts like Awesome Beauty or even a better Akard seemed far beyond me. And after two years I began to sadly realize that my flagship novel, despite three or four high-energy chapters, was overall rather dense and slow.

Thus I withheld the glories of The University of Mars from the world and withdrew from further publishing attempts. Not only was I even more reluctant to bring my work into the light, but I was also newly paranoid about the people in the process, assigning them the value of the Keepers of the Darkness.

Yet there were a couple good things that came out of the process:

- Writing those query letters and making those submissions gave me at least some confidence about writing to editors. The physical aspect of mailing envelopes and hardening myself to rejections was great experience, especially for the coming publishing pushes in 1992-95 and in the first couple decades of the next century. I was also surprised how rejection letters from story presses could get atrociously mean-spirited compared to the often-encouraging notes from novel publishers.

- More important was a major course correction; here I quote an essay from this period: I am shifting to novel writing exclusively. I have changed. I will no longer market “stories” but will instead concentrate all my energy to bring what’s hidden out into the open in the most effective manner; and that is novels. Stories are finger exercises, or at best interesting vignettes. Novels can present a world-view, by contrast, and as such they are so much more valuable.

Parts I and II

I still pushed on novels, even as the pressures of the library career and graduate school cut into my writing energies. After graduating in May 1985 I was ready to open up with some new fiction, and several dream vignettes coalesced into the surreal story “33” which in turn expanded to a new novel, Parts I and II. The blurb of that time:

I still pushed on novels, even as the pressures of the library career and graduate school cut into my writing energies. After graduating in May 1985 I was ready to open up with some new fiction, and several dream vignettes coalesced into the surreal story “33” which in turn expanded to a new novel, Parts I and II. The blurb of that time:

In Part I a naïve and disconnected artist gives a party to celebrate his career, only to find himself drafted that same night into a mindless war. In Part II he becomes a sergeant leading frightened yuppies against an unstoppable Army of Evil.

Parts I and II was a failed novel I soon realized I had no interest in rewriting; much of its turgid mood was colored by simplistic ruminations on what’s truly good and what’s truly evil. Its quasi-horror scenes look silly in retrospect. I did lift its best chapter for 1986’s Jack Commer, Commander, USSF, and that section became the basis for the Alpha Centaurian Grid which figures in subsequent Commer novels. By appropriating that chapter, I felt I’d effectively killed off Parts I and II.

Despite failing to cohere, I/II was a good expression, and it retained some interesting premises I couldn’t let go of; more below on how a couple more swerves put me into yet another ditch. Even so, many of this effort’s energies lingered into 2023’s Asylum and Mirage.

Backlash and New Exploration

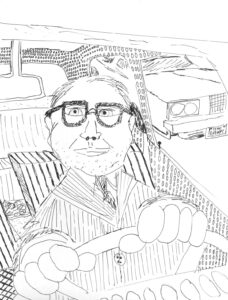

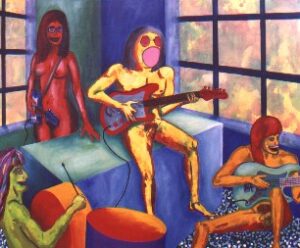

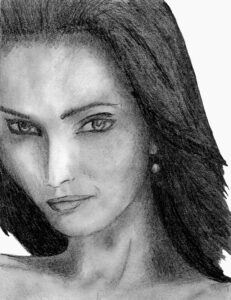

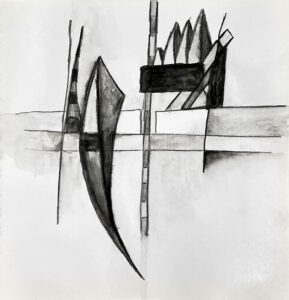

Jack as depicted in 1986

Then came a heartfelt protest against dreary publication efforts and the mushroom cellar feel of Parts I and II. I didn’t just let this swerve happen to me; I consciously pushed hard on a fresh creativity revolution through 1986.

In December 1985 my friend Sabin, preparing to go on a world tour with his new wife, sent me the entirety of my letters to him from 1962 to the present, and I’ve been the caretaker of our extraordinary correspondence since then. The letters inspired me to look at my eighth-grade novel, The Martian Marauders, abandoned twenty years before. I instantly knew it was time to complete that novel, pulling in new psychic growth in a fun science fiction format. I had to answer leaving my hero Jack stranded in a Venusian prison for two decades.

From the blog post The Irregular Origin of The Martian Marauders:

I was in the eighth grade in the fall of 1965. That fall and the following spring I got through 110 handwritten pages of a novel called The Martian Marauders, basically a Hardy Boys adventure set in space. But halfway through I got bored, and though I still have some rudimentary 1966 notes about completing it, I abandoned the novel, leaving Captain Jack Commer and his brother Joe hanging in the ventilation shaft of a Venusian prison for the next twenty years.

I effortlessly sketched a full outline of the rest of The Martian Marauders, and January 1986 saw an amazing rush of fiction. I later wondered if some of my problems of one-dimensional characterization and sloppy plot-making might have had origins in that unfinished eighth-grade novel; for I’d known even in March 1966 that I’d given up on it because I was bored with the characters and the plot.

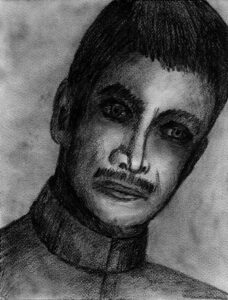

Amav as imagined in 1987

Part 2 had to not only complete the plot but also bring my central character, my self-image, up to date. Also challenging was explaining all the insane scientific errors of Part 1. Part 2 was the most satisfying writing I’d done in years. There were no psychological mistakes. I didn’t bore the reader or get sidetracked. I gave the one-dimensional space hero Jack Commer fits of jealousy, immature passion, and desperation, finally rewarding him with an excellent wife. Jack’s insecurity about Amav echoes the theme of existential combat against extraterrestrial monsters, and the eventual reconciliation between alien, warring cultures.

I typed Part 2 on my manual Royal 1940s typewriter, but the next month, with an eye to the emerging PC revolution, I used EasyWriter II to input 1966 Part 1 on a library computer. I saved the ancient document on a 5 1/4” floppy disk, and in 1991 managed to convert the file to WordPerfect. But I still didn’t consider computer input as real fiction, so I didn’t input Part 2 or consider this method for future writing until 1990.

The last chapter of The Martian Marauders explicitly requested a sequel. Thus Jack Commer, Commander, USSF, became part of 1986’s fun writing as it worked through some intriguing emotional themes. From the blog post, Jack Commer, Supreme Commander, with a Nod to the Crab Emperor:

A dream of the dismembered Crab Emperor effortlessly slid into the novel. Definitely powerful, and probably worth some psychological analysis. Translated into the novel, the dream pinpoints the moment when Alpha Centaurian Ship’s Archivist Polot discovers the true nature of his beloved Emperor, with whom twenty trillion Alpha Centaurians are expected to remain in constant telepathic contact.

Four of the chapters are crew diaries, each offering a different angle on the ongoing Centaurian attempts to convert Jack’s crew to worship of the Crab Emperor. As his Typhoon II personnel undergo alien brainwashing one by one, Jack Commer has ordered the surviving crew to keep diaries to track their mental states. But the diaries mainly probe or bounce off Jack’s shadow side as his confused, petulant, and even violent nature erupts in response to the crisis. The painful disintegration of his marriage is thrown into fresh light by his wife Amav’s last entry. And a near-catatonic twelve-year-old boy manages to tweak Jack’s ego with one final science fiction entry which Jack uneasily dismisses as pornographic.

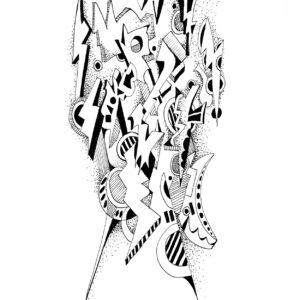

Amid the rush of The Martian Marauders and Jack Commer came new poetry along with Seeds of Sunshine, a sixth Oliver the Giant Cat collection of aphorisms. I’d compiled these through high school and early Rice, but had forgotten how much fun they were. I reopened visual art in 1986, completing ten paintings and sparking a renaissance that led in coming decades to numerous one-man and group shows.

I also set myself the task of reading books about creativity, but though they were somewhat absorbing, I discovered I just didn’t need them. Any fears of losing the creative spark had already been dismissed by the marvelous new 1986 output.

Sortmind

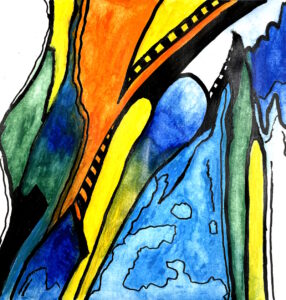

The painting Sortmind, 1988

1986 taught me to return to fun writing and be flexible. So what happened in January 1987 when it seemed time to give the entire Martian Marauders a second draft? I got off a decent new Chapter 1, but my library world chose this moment to decisively intervene.

I’d typed up one of my joke memos to pass around to my coworkers, positing a master science-fiction “sortmind index” to aid us in library work. But something hit me hard about that word, and I found myself hunting people’s desks and gleefully yanked my memo back before it got too far, because “sortmind” had suddenly become an urgent, copyrightable concept that mere coworkers must never know. Combined with a 1982 idea about a telepathic database that burns out subscribers’ minds, “sortmind” became a seed of a thousand-page rough draft.

I needed a millisecond to drop The Martian Marauders in favor of this new novel. Sortmind, 1987-1995, was the overwhelming success of this era. I knew it was a big book, no matter what flaws it might have.

There was certainly cause for flaws, since I declared I’d throw everything into this novel, including a freshman-year Rice story, my aborted Oliver novel, and my takes on library bureaucracy, urban politics, brain damage, fantasy life, architecture, power hunger, teen romance, and flying saucers. I stretched myself through dozens of characters and family intrigue going far beyond mere autobiographical expression. I kept my free-ranging science fiction motifs but considered Sortmind to be a literary novel.

Here’s the original overview, utilizing the stilted text of my 1992 query letter:

I am submitting my novel, Sortmind, for your consideration. A mixture of literary, science-fiction, and humorous techniques, Sortmind covers a period of two months in the city of Drulgoorijk’s increasingly violent architectural war: should tiny triangles be removed from post-modern buildings? Meanwhile the Telepathic Database, intended only as a convenient library reference tool, has not only been shown to be responsible for an ever-growing number of cases of Mindwipe in the city, but has begun acquiring an endless stream of random data which librarians finally suspect may indicate alien contact. Throughout this turmoil Oliver and Sam, two high school art students whose so-called fascist fathers head the reviled Citizens Against Triangles, struggle to define themselves in the face of urban warfare, the aliens, and the malfunctioning, reality-altering Database.

I typed Sortmind’s thousand-page first draft and almost all the second on my old manual Royal typewriter, then finally adapted to word processing. My wife and I bought our first $2,000, twenty-megabyte hard drive computer in late 1989, beginning with the primitive and buggy ProfessionalWrite which caused a few agonizing losses of text before we sensibly upgraded to Word Perfect in 1990. At first I went back and forth between typewriter and computer, but before long I was fully committed to computerization.

Property, a Gift

The painting Property, 1990

Property was one of the rare gifts that writes itself. It did so September 1990 to April 1991. It’s rare that something that needs to be said so badly that it flows out effortlessly, so much so that Property’s rough draft, with all its flaws and revision needs, reads more or less like the final 2020 version, retitled CommWealth.

The inspiration came from a February 1986 dream:

Character: Allan. An actor. Also supercilious asshole. Masks true identity. But he is aware of this problem–also doesn’t know how to get to the truth. His compulsive sexual fantasies destroy his sex life with his girlfriend, Ann. His whole life revolves around his fantasies. But he is such a good actor that he manages to pull off an acceptable front to the world. His penalty: that he doesn’t even know himself. His fantasies and sexual acts grow more and more absurd.

As story opens, Allan is walking, sees a Porsche or whatever, and asks the owner for the car. Owner must relinquish it. In the next pages we see, casually treated, an astonishing variety of “free transactions” like this. Everything is free in this society. You just ask for it. There is a 30-day waiting period before one “possessor” can ask for that same item back from the new possessor of it. There is subtle retaliation–for instance, the Porsche owner, while not allowed to act angry about giving up the car, does go ahead and ask for Allan’s coat and tie. Allan recognizes the maneuver–he always manages to make his askers “pay” somehow himself. The other technique is to hide as much of what you’ve got as possible. But these people are constantly castigated as “hoarders” and surprise inspections of homes, and publications of people’s inventories, are common. Often you are called up at night and asked for several of your items over the phone, with instructions on where to leave them for pickup.

Allan has adapted to this society well.

It may seem odd to wait four years to begin such a must-write project, but I knew the dream was a crucial one and that this novel would keep until I was done with Sortmind. The long gestation period allowed a wondrously tight plot to develop.

Property addressed ideas of privacy, which the CommWealth system would naturally strip away, as well as privacy’s darker sister, hiding. For the deep self was damn sick of hiding. But above all, it was the ensemble of characters and being fair to them that dictated what happened in this novel, not my personal urge to deal with life problems. I began to get clearer with both Sortmind and Property that though I always hoped to grow in understanding as a byproduct of novel-writing, trying to write a novel to cure yourself of some malady is folly.

Property was also the first novel I wrote from scratch in word processing. By this time I was quite facile with the process.

Another Lackluster Publishing Attempt

Sortmind and Property sparked a new urge to publish; these jewels just had to find resonance in the outer world. Aided by computer, I embarked on a more professional and assembly-line approach to query letters and sample chapters. Before useful email and Internet, these were sent through the mail, so the process for each submission might take weeks and sometimes months.

Yet I still held back, worried that I didn’t know what I was in for if I ever did get published by judgmental strangers in New York. I also despaired that I could ever be published, considering the millions of people clamoring for their first novels to become bestsellers. I came to see submitting a first-novel query letter as akin to buying a lottery ticket.

I forced myself to submit and resubmit, but wasted a lot of fearful time and energy on making publishing checklists, assigning myself meaningless research tasks, or making extra single-spaced “reading MSS.” in different fonts to lend to friends.

Sortmind went to thirteen publishers or agents, one of whom said he would read my 870-page manuscript for a dollar per page. He also said he really didn’t look at an envelope unless it said “Norman Mailer” on the return address. My novel’s final rejection came on March 31, 1995. I sent Property to thirty-eight publishers or agents, with final rejection on August 16, 1993.

That was enough for this round. I knew I was never supposed to give up, but I was just sick of the whole time-wasting process, and it was suppressing new writing. I was chagrined at the power of the literary gatekeepers and the logistics of just how long and costly it would be to send manuscript queries to a hundred publishers.

That was enough for this round. I knew I was never supposed to give up, but I was just sick of the whole time-wasting process, and it was suppressing new writing. I was chagrined at the power of the literary gatekeepers and the logistics of just how long and costly it would be to send manuscript queries to a hundred publishers.

It didn’t help that I was also ashamed at how much time I’d let pass since 1977’s “Space, Time and Tania” publication. I kicked myself for not following up more with PigIron magazine back then. Had I blown my only publishing credit?

I was struck by a strange disparity between marketing writing and marketing painting. You labor for years on a novel and spend another two sending out your queries, and if you’re lucky you get a small advance, or “contributors’ copies,” and then wait another year for publication. After that your baby is likely plunked into the remainder bin.

A novel is difficult for a reader to assess, because it requires a week, two weeks, or more, to get through and evaluate. Whereas a painting is apprehended immediately and either rejected or cherished instantly. So spending an afternoon on a compelling four-by-four-foot abstract painting might result in an immediate two-thousand-dollar sale.

So, I thought, maybe I should just do visual art?

Two really good novels going nowhere was daunting. What had happened to my ambition? Was writing really just a hobby? Why didn’t I want to interact with publishers? Was it an innate shyness of doing business with strangers, or a fear of exposing myself?

I did come up with a self-publishing concept at this time, based on my current knowledge of word processing. Though I had a vague understanding of the coming Internet, my concept revolved around printed books. Interestingly, the purpose wasn’t to become a publisher myself, but to interest a large publisher in Sortmind.

My four-page January 19, 1993 document went into surprising detail, considering typesetting, print costs, binding, design of title page, publisher name, page design, copyright, cover art, and blurb. The goal was to produce a high-quality mass-market paperback that resembled, and was priced comparably to, any science fiction or literary novel you’d find in a bookstore.

Marketing plans included a mailing list of friends, acquaintances, publishers, bulletin boards, and libraries. I figured a friend of a friend of a friend might be the one who made a breakthrough. I planned to offer the finished product to major publishers; to give the book to libraries; to send it to literary magazines; and to advertise the book electronically with an uploaded chapter. And a quaint phrase for 1993: “Don’t do this if it’s not considered ethical on bulletin boards. Would probably be fairly local at first–I don’t think the Internet would appreciate advertising.”

It was a good, confident dream I wasn’t quite up for, but it was prescient. It had no flavor of vanity publishing but pointed to a future where computer-wielding authors set their own rules.

A Hodgepodge of Moving Forward and Looking Backward, Revisions of Older Works, and Autobiographical Writing

I hurtled through this secondary ambition crash drifting yet again into backward-looking projects. I still thought 1985’s Parts I and II had merit and might be rewritten as yet another marketing scheme. After all, I was now working on a novel nearly every year and was feeling quite professional; and so in early 1992 it was time to embark on a professional job on I/II.

Notice and Dream Topology was a notable improvement on the first half of the novel. I restructured much, and the first six chapters of the first part, “Notice,” stuck with me for many years as a sort of complete Twilight Zone effort. I only wrote one chapter for the second part, “Dream Topology,” but it was a minor masterpiece in character interaction. However, my long-standing interest in acting and the theater, left over from my Rice days, intervened and I’m still not sure why I decided to convert this novel into a play. And why such a play should be so dreadfully bombastic. In any case I rewrote Notice and Dream Topology as play dialog and finished the second part using the old Part II of Parts I and II.

The resulting pollution, Linstar, is probably the only writing I’m truly ashamed of. Both my readers evinced extreme disgust. The only valid explanation for why this suddenly professional-feeling writer should veer into such a disaster is the word “hubris.”

I’ve kept the digital file of the damn play and actually consulted it for any clues as to where Asylum and Mirage of 2022-23 might go. Not only were there no such clues, but even reading this putrid work thirty years later was nauseating.

At the time, July 1992, I was so sobered by my wife’s reaction to this dismal thing that I told her I had to immediately embark on a nourishing soul project. “Are you going to rewrite Akard?” she said, reading my mind.

A painting for Akard, 1993

I definitely felt I’d put Akard Drearstone to rest when I mothballed a pile of chapters into New Akard 1979. But in the liberated energies after finishing graduate school in May 1985, I updated its characters a few years after the novel’s action in a story, “Chapter 32.”

Did this story flow easily because I deliberately used an older style with familiar characters? There’s much truth in that; it was easy to draw on my knowledge of the ancient characters’ motives, and the familiar style did come quickly. But I kept pushing my present self into it.

In any case, I now had a germ of a revision lurking from seven years before. After the 1992 Linstar catastrophe I needed something fun and meaningful. I rewrote Akard with a fresh concept of trying to put myself inside the mind of a twelve-year-old girl as the main character. The resulting 1992-94 Akard Drearstone was fresh and energetic

I needed Akard 1992-94 to center myself, but it had still been based on looking backward. By this time I was feeling guilty about my urges to rewrite old works. Was I just seeking refuge in comfortable, ready-made ideas instead of embarking on uneasy exploration? I also looked upon my past, specifically college, as potential plunder.

The themes of an ongoing set of notes called “Second Semester Sophomore Year,” an experiment in recalling every single event that transpired in Spring 1972, had found some expression in The University of Mars, but I never felt I’d really nailed the account of the Rice era, specifically some of its astonishing coming-of-age experiences, or the amazing arc of 1973.

April 1972

So I went with more past-tripping. In addition to the “Second Semester Sophomore Year” notes, over the summer of 1993 I put together additional source material: sixty pages of excerpts from letters, journals, poems, and other sources from 1971-1974. My aim was to be completely truthful about what actually happened. I knew I wasn’t writing fiction and set down everything I could remember, even if a given detail didn’t fit smoothly into the narrative.

Several events had already been the focus of fiction, especially in the rough draft of Akard Drearstone where I recreated experiences as accurately as possible from a distance of only a few years. With some edits in the interest of truth, these accounts occupied much space in the memoir. I was close enough in time when I wrote them, and the experiences were so deeply etched into me, that I trusted their dialog and detail to be reasonably accurate.

The resulting 344-page manuscript was necessary writing and incidentally tutored me in the vexing issues of autobiography. It doesn’t strike me as self-serving; I enjoyed making fun of my more ridiculous actions during that time. While it was another backward-looking project, and written during the rather dreary era of the second-tier publishing push, it cleared the way for entirely new writing as well as more sober methods for dealing with the publishing world. By late 1994 my flagship novel The Soul Institute was on the horizon.

Copyright 2024 by Michael D. Smith

A Writing Biography, Part I: First Efforts in The Gore Book

A Writing Biography, Part II: The Blue Notebook

A Writing Biography, Part III: Unhappy Kid Interlude, Yet Two Novels, Sort Of

A Writing Biography, Part IV: The Perfect Cube and Beyond

A Writing Biography, Part V: Space, Time, and Tania through The University of Mars, 1974-1982

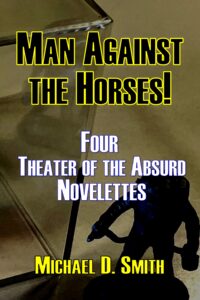

Bumbling officer Marty Brimfeeler probes the death of a brainwashed terrorist in Houston. Five horses break out of their corral and reduce the city of Dallas to rubble. Hapless insurance executive Bobby Thompson proves his manhood on the mean streets of Dallas. Special agent Atoka surveils Houston on his nuclear-powered bicycle until software glitches trap him on a coastal freeway.

Bumbling officer Marty Brimfeeler probes the death of a brainwashed terrorist in Houston. Five horses break out of their corral and reduce the city of Dallas to rubble. Hapless insurance executive Bobby Thompson proves his manhood on the mean streets of Dallas. Special agent Atoka surveils Houston on his nuclear-powered bicycle until software glitches trap him on a coastal freeway.