It’s been difficult to write 1994-2011; this is quite a long era, from my thirties to my fifties, with several deluded sub-eras as well as breakthroughs. But the period seems anchored at each end: beginning with The Soul Institute charting a new course in my writing, and ending with a publisher accepting The Martian Marauders.

Some of the sections below are quite short, others more involved. But each is a psychic milepost along the way.

The Soul Institute, 1994-1999

The Soul Institute was the most problematic of my novels to write, but apparently needed to be. It eventually emerged as my flagship novel.

The Soul Institute was the most problematic of my novels to write, but apparently needed to be. It eventually emerged as my flagship novel.

I began compiling ideas in 1993, including memories of ninth grade and the surreal dreams of returning to a college paradise which was sometimes Rice University, sometimes a vision of the Other World. The gloriously numinous first draft was also a disordered, problematic, sprawling, 381,949-word, 1,354-page first-draft mess.

At times I considered abandoning the novel, taking a years-long vacation from all writing, or abandoning writing entirely in favor of visual art. There was something frustratingly unfused in the first draft even as fascinating events and characters kept emerging. Finally the second draft’s major plot reorganization brought out a central vision based on those characters.

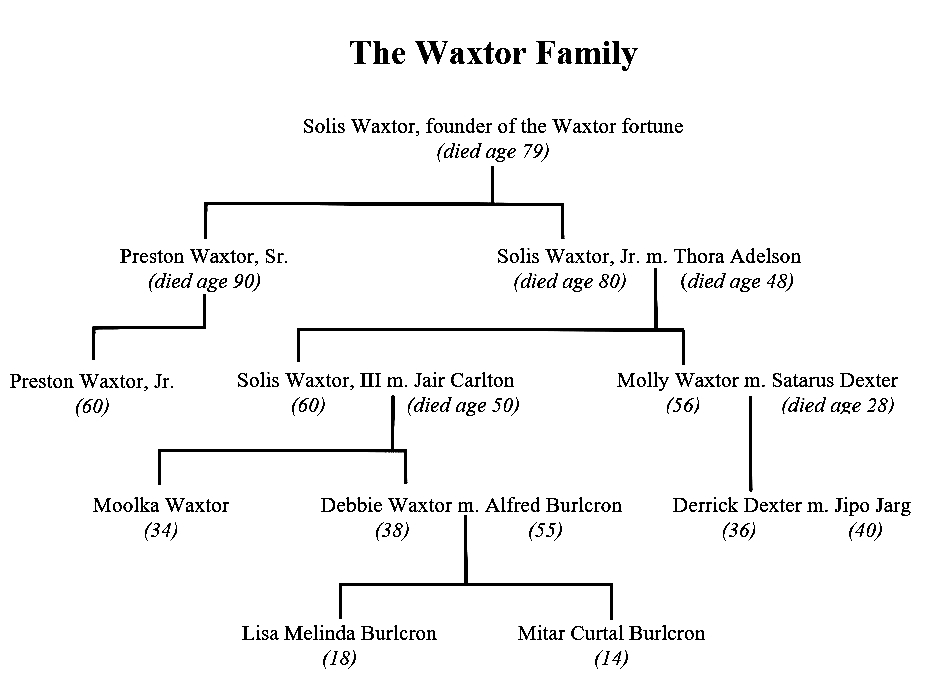

The novel describes a chaotic November at a small Texas coastal university founded on royalties from the director’s bestselling novel.

Several character groups eventually collide: the Soul Institute administrators and faculty pursuing power struggles and fantasy life in an increasingly malignant bureaucracy, the students who came to live the life of Soul but find themselves dismayed by the underlying chaos; and ninth graders at the local junior high pursuing inhalant abuse and gang violence,

I’d finished what I thought was a final manuscript in December 1999, and was proud of the result. Yet, inexplicably, I placed the manuscript securely in the desk drawer for over a decade. I think this was primarily because I assumed that an offering of 1,064 pages and 266,000 words by an unknown author could never be considered by traditional publishers. I had an idea of getting one of my shorter novels published first; then The Soul Institute might be considered for a second one.

I’d assumed that this novel was so well done that it might just need a little light editing. So I was surprised to reread it in 2009 and find it needed a thorough revision. Two more drafts rearranged and simplified its plot, cutting the length by about twenty-five percent and reducing a great deal of interior character thinking and expositional verbiage.

My goal in The Soul Institute was a Shakespearian fairness to all characters. Each character, no matter what his or her moral or mental state, no matter how noble or ridiculous or pathetic, is an actor on the stage of the novel, to be respected and understood, given time to develop, and integrated into the framework of the story. I wanted to present all these character entities to an ideal reader. This ideal reader is sometimes myself, especially in editing mode, but almost always winds up going beyond my personal concerns and strives to connect with other human beings who are open-minded and curious, willing to both severely judge my writing and learn from any honest energy in it. You want the writing to be as perfect as can be for this reader.

Life events during this period all had their influence on this novel:

- I moved from my Texas History librarian position to be Dallas Public Library’s first webmaster, also dabbling in desktop support and network analyst roles, but by the end of 2000 I was done with this direction and returned to regular work as a branch library assistant manager. During this time I got involved with the first expansion of the Internet, including creating my own website.

- I also dealt for three years with a head infection, finally cleared up in 1998, from a childhood car accident.

- Cats entered our lives. Soon my wife Nancy and I had nine.

Another Lackluster Publishing Attempt

I covered this topic in A Writing Biography Part VI. But I quote from it because this attempt ran concurrent with The Soul Institute and is still an accurate assessment:

Sortmind went to thirteen publishers or agents, one of whom said he would read my 870-page manuscript for a dollar per page. He also said he really didn’t look at an envelope unless it said “Norman Mailer” on the return address. My novel’s final rejection came on March 31, 1995. I sent Property to thirty-eight publishers or agents, with final rejection on August 16, 1993.

That was enough for this round. I knew I was never supposed to give up, but I was just sick of the whole time-wasting process, and it was suppressing new writing. I was chagrined at the power of the literary gatekeepers and the logistics of just how long and costly it would be to send manuscript queries to a hundred publishers.

My publishing query eras through 2011:

- 1975-ca. 1977: numerous story submissions, during which time “Space, Time and Tania” was published.

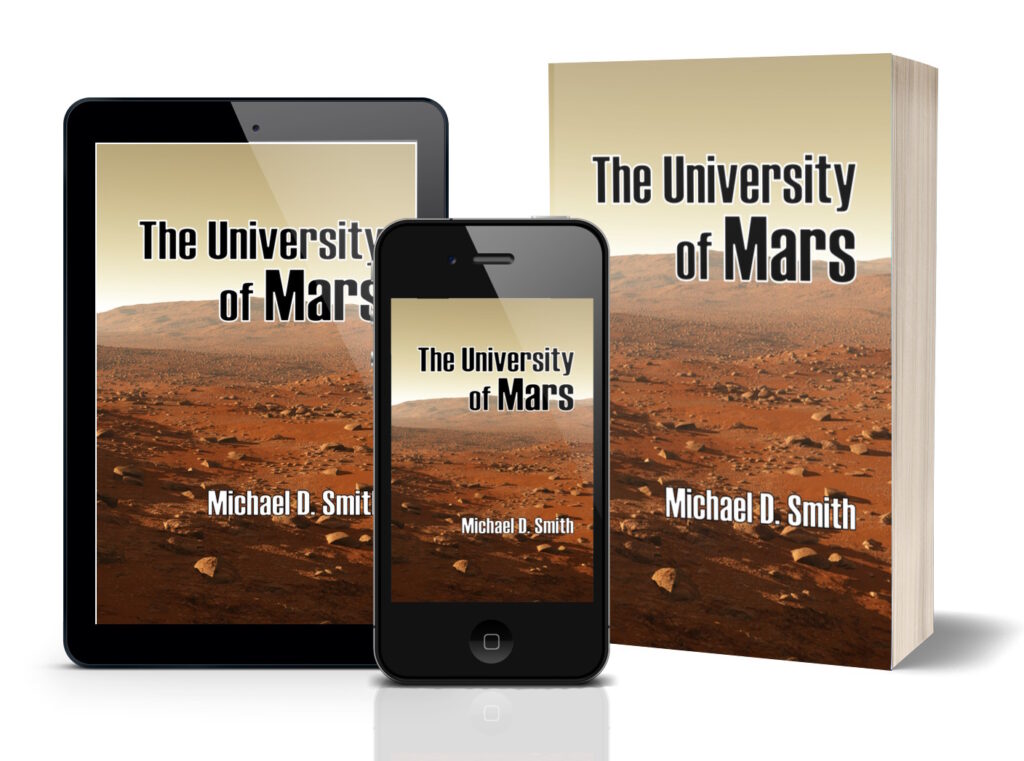

- 1980: “Where Eagles Have Unfortunately Landed,” a silly story slated to become part of my novel The University of Mars.

- 1984-86: The University of Mars and various stories intended to pave the way for that novel.

- 1991-1995: Sortmind and Property

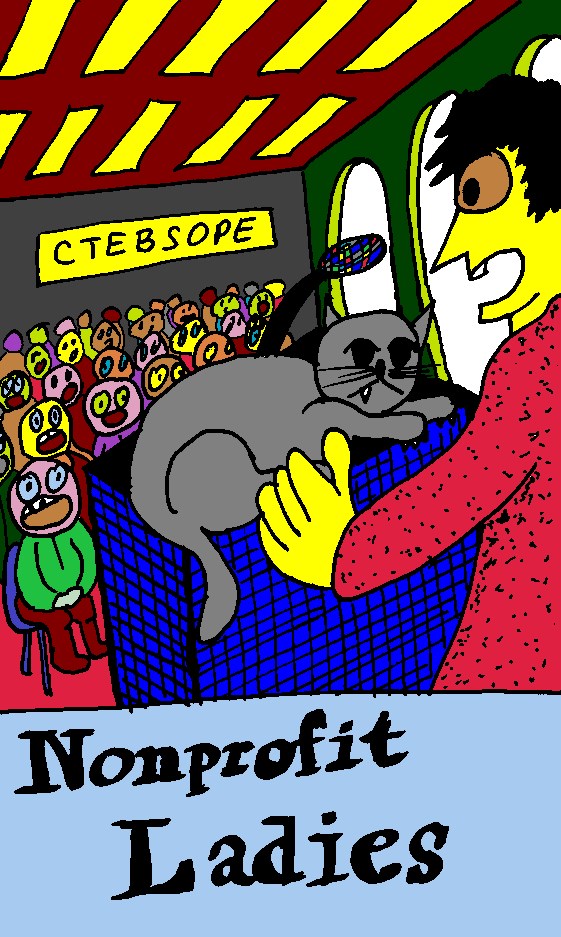

- 2003-2004: Nonprofit Ladies

- 2008-2011: “Perpetual Starlit Night”; “Starvation Levels of the Infinite”; Sortmind; Jack Commer, Supreme Commander; Nonprofit Ladies; The University of Mars; The Martian Marauders.

I declared around this time that the only thing I had true control over was the quality of my own writing. This concept became a challenge to take up over the next few years.

The 1996 First Twenty Steps Revision

The First Twenty Steps was a useful experience in eventually moving to self-publishing. A friend of Nancy’s read this novella and suggested that her father, who was starting a publishing company, might publish this 1984 tale of an ex-convict who finds himself mixed up in a motorcycle gang’s plan to heist a hyperspatial supercomputer. It was a tight, well-plotted story, but she had suggestions for a more concrete ending. I revised the book and emerged with a much stronger novella. It was exciting to encounter a new era in publishing with small independent publishers. I wasn’t too disappointed when the publishing company concept didn’t pan out; I’d managed to improve the novella and now considered it publishable.

Though I never tried to market the new digital version, in retrospect it seems that I knew all along that this novella was fated to eventually be my first self-publication; of course this is hindsight, but something about this feels right.

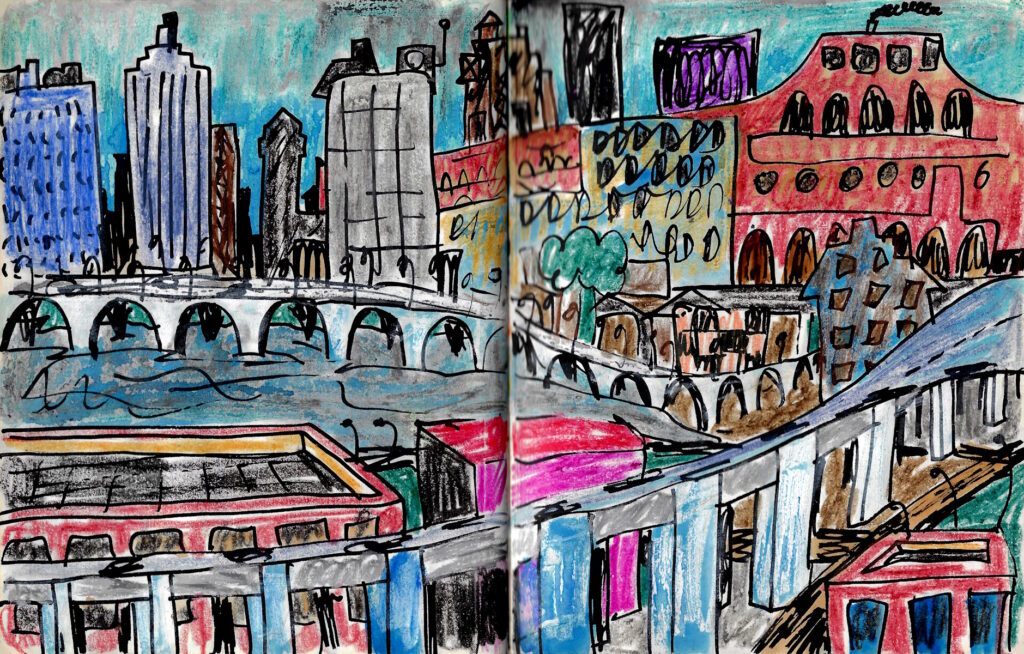

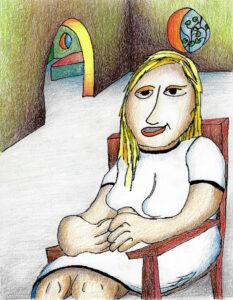

Art vs. Writing

I also touched on this topic in A Writing Biography Part VI: the different ways of marketing writing and visual art. You labor on a book for years; judging its merits requires a few days or weeks for reading and reflection. Whereas a painting hits you in an instant and you form an immediate assessment. You may even impulse-buy it. Thus a few hours or days on a single painting would probably net you more income than a novel taking six years. So sometimes I wondered if I shouldn’t chuck writing and just paint. After all, my painting energies had been ramping up since 1986, and I had dozens of completed paintings to show.

I also touched on this topic in A Writing Biography Part VI: the different ways of marketing writing and visual art. You labor on a book for years; judging its merits requires a few days or weeks for reading and reflection. Whereas a painting hits you in an instant and you form an immediate assessment. You may even impulse-buy it. Thus a few hours or days on a single painting would probably net you more income than a novel taking six years. So sometimes I wondered if I shouldn’t chuck writing and just paint. After all, my painting energies had been ramping up since 1986, and I had dozens of completed paintings to show.

Starting in 2003 I had numerous art shows, some one-man, others group shows, and sold a handful of works. It was an eye-opening experience, and I met some wonderful artists along the way.

My last show was in August 2011 at the Renner-Frankford Library. I’d simply gotten tired of the effort involved; staging even a small show is a major undertaking. This one also reverberates because I designed it to showcase my recent experiments in painting very large, like seven by eleven feet, on unstretched canvas. It seemed like a fitting end to art shows. Of course, I may do more in the future.

Sortmind.com, 1999

In July 1999, during the time I was working as the Dallas Public Library webmaster, I was sent to a Dallas Morning News seminar about publicity for nonprofits. In an afternoon session I was abruptly inspired to create sortmind.com. I had enough webmaster knowledge to design a decent site, but had to stretch a bit to get it properly set up. I’ve always been proud of its October 24, 1999 start date; yes, I have a website from the twentieth century. I also named Sortmind Press after it.

The website functions as an overview of my writing and art, and I keep it current, both in content and technologically–though I don’t go all-out on the tech. I consider it indispensable to my marketing efforts, such as they are.

Nonprofit Ladies, 2000-2003

After finishing what I thought at the time was the final manuscript of The Soul Institute, I had the urge for another literary novel, but I wanted something more condensed than the exhausting Soul Institute. My library tech work and a new restlessness to move beyond it was one of the subthemes.

After finishing what I thought at the time was the final manuscript of The Soul Institute, I had the urge for another literary novel, but I wanted something more condensed than the exhausting Soul Institute. My library tech work and a new restlessness to move beyond it was one of the subthemes.

The original idea sessions became an arts and crafts project in sorting disparate ideas jotted down over the years, along with folders of photos, clippings, newspaper and magazine articles, recent dreams and any older writing that attracted my attention. Before long I had seventeen categories and I glued the most relevant clippings and notes onto seventeen large posterboards:

- Animals–Wild / Nature / “Physics”

- Raw Tao

- Zany / Future / Sci-Fi

- Nonprofit Ladies

- Big Shared Nightmare

- Children / Beauty

- Libraries / Preservation

- Sorrow / Passion

- Art / Raw Energy / Sex

- Zen / Taoists / Science!

- Old Things–People–Society–Methods / History

- Absurd / Humor

- The Aristocracy

- Animals Interacting With Society

- Kids in Trouble

- Politics / Civilization

- Overviews

Then a poignant dream of “hyperlink teleportation” veered the novel into science fiction. At first I thought that Jack of 1986’s Jack Commer, Supreme Commander, was going to be a central character. Then I realized this would fall to his troubled younger brother, copilot Joe Commer.

Within three years I had the third part of a trilogy, completing The Martian Marauders and Jack Commer, Supreme Commander. Nonprofit Ladies could also stand on its own as a novel of current themes, and I sent two queries on it through 2004. Nancy was a major help when she went to a publishing seminar in 2003 and came back with the concept of sticking to Times New Roman 12 (instead of Courier 10) and sending thank-you cards. This helped me be more professional in my approach. But I think I knew unconsciously that Nonprofit Ladies wasn’t what it should be.

The 2002 Novel Urge and Perpetual Starlit Night

During the stressful period when Nancy and I were moving to Richardson and selling our Dallas house, even as I worked on Nonprofit Ladies, I kept envisioning another vast new novel on the scale of The Soul Institute. But after plundering my journals for ideas and sorting characters and plot ideas on notecards, I soon began to see that while there were some decent concepts there, I wasn’t in shape for a new novel. All I really had was another Soul Institute family saga, a clone of that previous novel.

Though I abandoned “New Novel” in September 2002, its ideas still called to me, and three years later I tried to shove them into a science fiction novel called Perpetual Starlit Night. But once again realized I wasn’t interested in the concept. “Perpetual Starlit Night” was really a short story, which I finally wrote in 2007, in which an archeologist arrives on a tiny artificial gravity platform in deep space to give a scholarly lecture to barbarian colonists, only to find that she, like them, is being incarcerated here as a barbarian criminal herself. The story was later published in Double Dragon Publishing’s 2013 anthology, Twisted Tails VII. I improved it and placed it in my collection, The Damage Patrol Quartet, in 2021.

The lesson here was learning not to be desperate for a novel. Don’t push things. You know when it’s the right time to move on fiction, and what the correct form of it should be.

Akard 2005 and the Italics Aberration

I began the Akard Drearstone 2005 Project intending to make a quick edit to address a flawed scene in the 1994 novel’s first chapter, but wound up revising the entire novel. But unfortunately–I still can’t fathom why–I wallowed into a bad writing habit which later polluted other writings.

I began the Akard Drearstone 2005 Project intending to make a quick edit to address a flawed scene in the 1994 novel’s first chapter, but wound up revising the entire novel. But unfortunately–I still can’t fathom why–I wallowed into a bad writing habit which later polluted other writings.

This is the overuse of italicized thinking. Again, this relates to desperation to be published; I truly thought I could translate existing character thinking narrative into italicized thoughts to give the characters immediacy and high energy, jazzing up my books and making them more query-alluring. It was truly yucky in retrospect, but I continued to overindulge in this technique as I revised other novels during this period, including the three Jack Commer novels, Sortmind, The Soul Institute, and Property/CommWealth. This was a major negative detour. A small amount of italics is a spice, but I’d piled insane amounts of salt and curry on the text.

I eventually discovered that almost all character introspection works better as narrative rather than as present-tense italicized thoughts. Fortunately I came to my senses in 2015, and I’ve de-polluted all my novels since then, including ones already published.

Organization and Lost Energies

During 2000-2010 I found myself cleaning up past writings, not only to have publishable material on hand, but also to come to grips with the body of fiction I’d created over the decades. This included revising works of value, digitizing but not revising older works, and fashioning a couple new collections. I also began writing some new fiction.

Revised works:

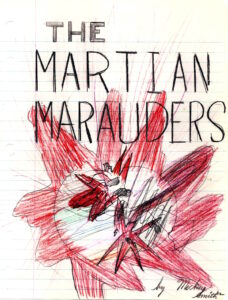

- The Martian Marauders – revised 2003-2010

- Akard Drearstone – rewritten 2004-2005, revised August 2010

- Jack Commer, Supreme Commander, USSF – revised 2005-2010

- Sortmind – revised 2006-2009

- Nonprofit Ladies – revised 2006-2010

- Property / CommWealth – title changed 2009, rewritten 2010

- The University of Mars – rewritten 2009

- The Soul Institute – revised 2010

Digitized but left as archival editions:

- Nova Scotia (1973) – scanned and copyedited, 2006

- The Fifty-First State of Consciousness (1973) – scanned and copyedited, 2006

- Zarreich (1981-82) – scanned and copyedited, 2006

- Parts I and II / Notice and Dream Topology (1985) – scanned and copyedited, 2006

- Plus numerous old stories, a few of which wound up in story collections Man Against the Horses! and The Damage Patrol Quartet.

New compilations from throughout my writing history, not for publication:

- Poem Compilation, 2007, adding new as found or created

- Essays Compilation, 2008, continued to the present

New work:

- Ocean Singe Horror, 2008 – a novel based on a ninth-grade short story, later titled Jump Grenade.

- Seven of Cups/Beyond DamnStar, 2011 – a novel which became Collapse and Delusion, the 4th Jack Commer novel.

It felt appropriate to contact this past (and lost) energy, to reread things I’d forgotten writing, and to recall how they once reverberated with other people. There is some good writing from 1981 on, no doubt about it. But I traced a mixture of delusion and dogged underground courage, with the final result a collection of passionate but flawed artworks along with the sharpening of some skills.

The Summer Art Career

As I approached early retirement from Dallas Public Library in April 2006, I’d been putting new energy into painting and art shows. My former psychic balance of 80/20–eighty percent of my energy devoted to writing and twenty percent to visual art–was veering toward 50/50. I seriously figured that I could sell paintings and stay afloat with the proceeds along with some part-time art gallery job. Hmm. Over the summer I pulled together my fanciest marketing ploys and visited numerous galleries in Dallas hoping to make some contacts and sell some art.

I saw abstract work similar to what I was doing, some worse, some much better. I also saw a wall-engulfing dull abstract in the design district with a ridiculous $32,000 price tag. Along the way I had a phone call with an art expert who wanted to know who I’d studied with–or should study with–at the proper university MFA program. I felt my energies draining in response. The insider contacts and the weird aristocracy of the gallery world were stifling. I didn’t want to compete with that stuff, hell, I didn’t even want to know it. I didn’t want to be in a studio every day churning out the improvised abstracts, nor for that matter did I want to be matting and framing a thousand drawings.

I got some of this out in 2008’s Ocean Singe Horror, featuring an art gallery owner and his daughter receptionist. This chapter title expresses it:

Snooty Art with Sexy Receptionists, or, Her Outfit for Any Given Day Costs More than You Will Ever Make Selling Your Paintings

While I considered myself professional enough to put my work up against other abstract artists, I now knew I wasn’t about to give it that final ambition push. Painting is necessary but it does exhaust me. It serves a psychological need that doesn’t translate into “art career.” It’s more than a hobby. It could even be a laid-back business, but it’s not a career. Whereas I literally can write every night, gaining energy each time. My real talents and love are in writing, and I wonder how I ever could have thought otherwise.

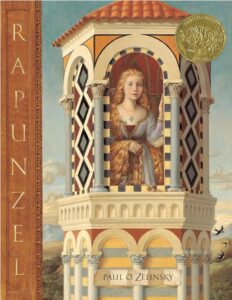

A final August 2006 visit to the Irving Arts Center nailed this realization. In a far sunny gallery were Paul Zelinsky’s wonderful original drawings for his book Rapunzel. What a moment that was for me, to see such excellent drawing and color in service of the story. I realized my own visual art was literary after all.

A final August 2006 visit to the Irving Arts Center nailed this realization. In a far sunny gallery were Paul Zelinsky’s wonderful original drawings for his book Rapunzel. What a moment that was for me, to see such excellent drawing and color in service of the story. I realized my own visual art was literary after all.

The Summer Art Career ended that instant.

I still showed paintings in various art shows through 2011, but I never returned to that deluded 50/50 balance. In August 2006 it was time to fully return to writing, but first, economic necessity brought me back to the library world. I figured it would again be a good place to nurture the literary energies. One interview at McKinney Public Library obtained a reference librarian position. No supervision, just good old-fashioned librarian work. I had no idea it would be the background for sixteen more years of libraries–even as the library hurtled into the technological future, dragging me along with it.

Right before starting that new job I painted a corner of my studio, a farewell to the Career.

The 2006 Vulgarity Insight

Three months into my stint at McKinney Public was the setting for a thoroughly unexpected November 2006 realization. A night at the Nonfiction Desk was quite slow, so I perused the HTML text of Nonprofit Ladies which I’d recently put on sortmind.com, unlinked so I could show it to only a few chosen readers. Keep in mind that although I’d broken off trying to send query letters on this book back in 2004, I still considered it a magnificent jewel.

I was prepared to find a few typos I’d later correct. Instead I was stunned to find broad strokes of vulgarity in Chapter One. This had never occurred to me before. Yes, my early writing during the ’60s-’70s counterculture had certainly been influenced by the new freedom to employ whatever obscenities we wished, but even my 1,587-page, 1976-1978 rough draft of Akard Drearstone hadn’t had this cynical, putrid feel. It wasn’t the story itself that was bad, or even the actual foul language, it was rather a weird, sarcastic, flippant tone that somehow surfaced behind my back the past few years. The Soul Institute Draft One, 1994-1997, didn’t have that feel, either. Where on earth had this come from? Was I trying to be flashy for publishers?

I was prepared to find a few typos I’d later correct. Instead I was stunned to find broad strokes of vulgarity in Chapter One. This had never occurred to me before. Yes, my early writing during the ’60s-’70s counterculture had certainly been influenced by the new freedom to employ whatever obscenities we wished, but even my 1,587-page, 1976-1978 rough draft of Akard Drearstone hadn’t had this cynical, putrid feel. It wasn’t the story itself that was bad, or even the actual foul language, it was rather a weird, sarcastic, flippant tone that somehow surfaced behind my back the past few years. The Soul Institute Draft One, 1994-1997, didn’t have that feel, either. Where on earth had this come from? Was I trying to be flashy for publishers?

Or had I deliberately engineered a flawed and unpublishable novel? And in so doing kept myself insulated from the world of expressing, publishing, distributing, discussing, influencing? Would true success scare me? Did I secretly wish to stay hidden?

I still don’t know why my style veered in this jeering direction. I don’t even want to go find that 2003 manuscript and confirm what I saw that November night. In any case I realized that Nonprofit Ladies was anti-self and had to be immediately and thoroughly rewritten. This also implied checking the recently revised The Martian Marauders and Jack Commer, Supreme Commander for similar issues, but later rereadings confirmed that Nonprofit Ladies was the main recipient of the mysterious sordidness.

The need to revise Nonprofit Ladies completed the transition back to putting writing first, to the original 80/20 balance. The December 2006 painting, “16. Tower,” describes both the end of the Summer Art Career and the full turn back to writing. Observe what my protagonist holds onto and what he lets go.

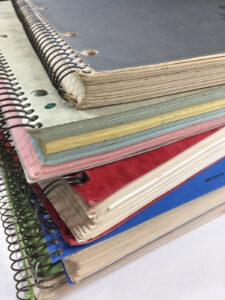

The 2009 Digital Journal

I’d kept handwritten writing journals since 1969, but in late 2008 I spent a few hours reexamining my commitment to paper. I was surprised how fast I talked myself into a word-processed journal, how quickly I took to it in practice, and how useful it’s been since.

I’d kept handwritten writing journals since 1969, but in late 2008 I spent a few hours reexamining my commitment to paper. I was surprised how fast I talked myself into a word-processed journal, how quickly I took to it in practice, and how useful it’s been since.

I mulled various drawbacks of paper notebooks:

- Difficulty deciphering my own handwriting.

- Not searchable, not copyable for use in essays or fiction.

- Inability to edit.

- Problems with ink bleeding through paper, fading over time, or even photocopying well.

- Susceptibility to fire, wrinkling, tearing, water damage, cat damage.

- Only one copy. No offsite storage.

I began the digital journal on January 14, 2009. I eventually worked out a method for adding entries throughout the month, proofing them as I went along, then printing one month at a time for a binder. Each year is one Word document. I’ve slowly been inputting previous journals, though this turns into an immense task reserved for fallow periods when I’m not engaged in new fiction.

The ability to search all the journals has been remarkably useful. My journal persona–somewhat related to my blog voice or letter-writing voice–has continued to evolve. Yet I’ve never been inclined to put the journal on some cloud-based app.

Sortmind Revisions in Light of Publication

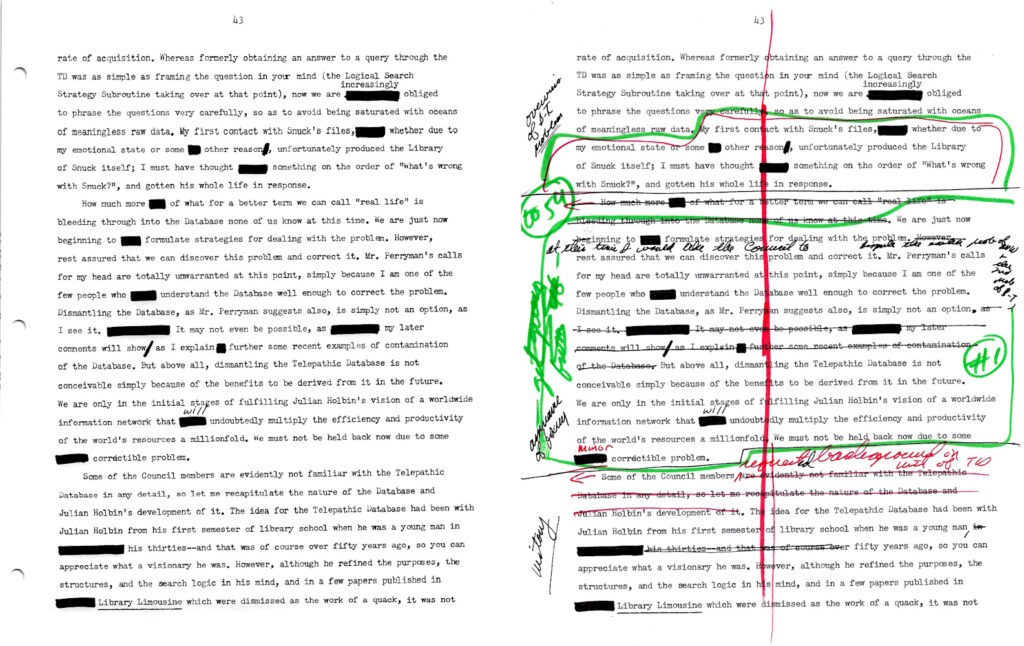

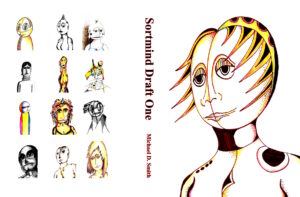

In November 2005 it was time to revisit the 1994 Sortmind work and bring it up to date, but the Summer Art Career interfered, along with the revision of Nonprofit Ladies. By February 2007 I had a new and better Sortmind which, in retrospect, I call Draft 4; this relegates the 1994 “final MS.” to “Draft 3” and explains how Sortmind wound up with nine drafts before publication in 2019.

In November 2005 it was time to revisit the 1994 Sortmind work and bring it up to date, but the Summer Art Career interfered, along with the revision of Nonprofit Ladies. By February 2007 I had a new and better Sortmind which, in retrospect, I call Draft 4; this relegates the 1994 “final MS.” to “Draft 3” and explains how Sortmind wound up with nine drafts before publication in 2019.

Of course Draft 4 was now crammed with the italicized thinking which so wondrously warped Akard Drearstone. Sortmind’s translations into italics were even more mechanical than Akard’s and boring to execute; I’m not sure why this wasn’t self-evident to me at the time. Yes, I improved the book in terms of updated characters and plot, but Sortmind was truly marred by this italics silliness intended to captivate publishers with the novel’s “high energy and emotional resonance,” as my query letters put it.

I should start every paragraph in this essay with this Richard Feynman quote:

“The first principle is that you must not fool yourself, and you are the easiest person to fool.”

Desperate to market a long novel, I had the further bright idea of casting Sortmind into a trilogy, grandly titled “1. The World is an Art Supply; 2. Awaken the Sleep Within; 3: Pledge of Resistance, or Let Me Shatter Your False Assumptions and Replace Them With Some of My Own.”–this later “improved” several times, but who cares?

One of the editors I queried saw through the ploy, saying each sub-novel was too short and the thing as a whole too long. I had to admit that the book was never a trilogy but one big novel. By 2010 I’d gotten Sortmind formatted into one Word document and though I again called it my “manuscript,” it was really just Draft 6.

The lesson here was again, desperation leads to screwing your art. I also think I also knew by this time, but probably wasn’t ready to admit, that the 1980s architecture of this book was no longer working.

But all this was one more learning experience.

New Publishing Attempts

With numerous revisions underway I again turned my thoughts to the idea of sending off short stories as more cannon fodder to gain writing credits, then, as I discovered the new paradigm of eBooks underway, I began gearing my efforts in that direction.

In 2009 I overhauled my 1984 novel The University of Mars; it was a major reboot, structurally superior to its first version, but its over-the-top italicized thinking rendered it hard to slog through. Yet I considered The University of Mars as an ideal eBook candidate, along with The Martian Marauders.

Somehow this entire publishing effort started to feel better, especially when I began to interact with people who’d published eBooks and who were outside mainstream publishing. Though I knew there were flaws in my previous works, I was working to correct them. My early twenty-first-century revisions, uneven as some were, were pointing to new contribution. If you’ve completed the best manuscript you can and honestly send it out, you’ve done what you should. If the outer world is not fated to pick it up, so be it.

A tip I picked up from interacting with eBook publishers was getting all my manuscripts into one-file format. So far I’d gone through the word-processing era by making each chapter a separate document, fearing a whole novel file might be too large, but later I found that Word can handle a 32,000-page document.

The Blog, 2010

After much thought I began blog.sortmind.com, a WordPress blog, in August 2010. I knew from the beginning that it would go far beyond sortmind.com’s “repository” nature and involve communication, opinions, feedback, and community. It would stretch my conceptions of what I did on the web.

After much thought I began blog.sortmind.com, a WordPress blog, in August 2010. I knew from the beginning that it would go far beyond sortmind.com’s “repository” nature and involve communication, opinions, feedback, and community. It would stretch my conceptions of what I did on the web.

I had a backlog of essays as well as journal musings, which gave a hint of what I might be working on. I conceived of sample writing on various topics, clean, blunt, and purposeful, which others could comment on or not. I also wanted to showcase my visual art. But somehow the visual would all still be literary.

At the time I wrote the below in my journal, and it still applies:

I think above all the point is not to have any expectations of “success.” I do want the thing to just be fun and yet also “sober/responsible.” My art and writing are important to me and I don’t want to trivialize them or get involved with lowlifes, inflammatory opinions, or general Internet bullshit. Nor do I need any sort of diary or to get personal/confessional. In no way do I conceive of this blog as anything like Facebook or “social networking.” I can appreciate how blogs have developed as structured personal websites with comment and networking capability, I can now see the point of them, but for myself, I just want to master the game as self-expression, and see where it leads. I really don’t have expectations that it can lead to literary success, although it can be that “repository” for interested parties to see how I write.

The First Twenty Steps 2011 and PubIt

The 1996 revision of my novella The First Twenty Steps proved prescient in late 2010 when Nancy got interested in Barnes & Noble’s Nook e-Reader and found out about the PubIt self-publishing platform, which has since morphed into Barnes & Noble Press. A crisp 25,000-word novella seemed just the thing to experiment with self-publishing.

I polished the 1996 manuscript and followed the at-the-time arcane PubIt instructions for getting the thing online as a Nook eBook. My first time doing this was anxiety-laden, anything but the routine way I publish on various platforms now.

The PubIt site asked me to name my “publishing house,” so naturally I settled on Sortmind Publishing. Later I preferred Sortmind Press, which has a more Gutenberg feel about it.

The First Twenty Steps debuted on PubIt on January 28, 2011, and publishing suddenly went from a decades-long unattainable dream to something I could have total control over. Yet I still thought of The First Twenty Steps as an experimental contribution, some sample work that might lead me to other publishers, and I began feeling out new marketing techniques via email, my website, and of course my new blog.

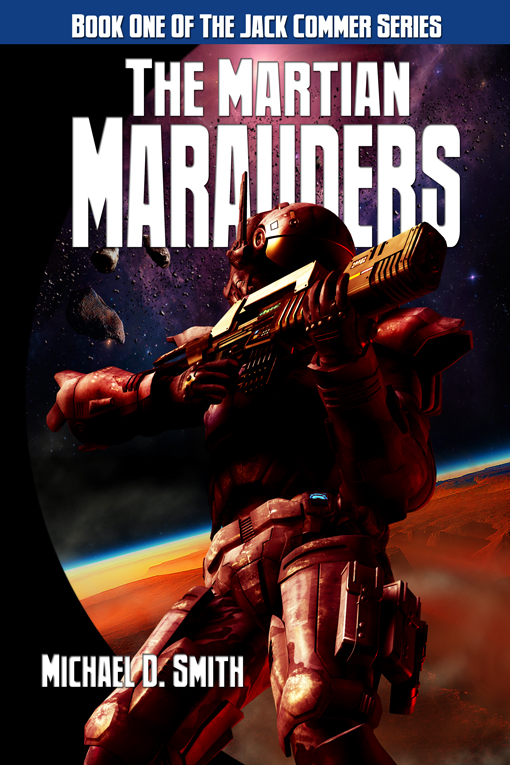

The Martian Marauders is Accepted

In 2009 and 2010 I sent queries to agents or publishers on The Martian Marauders (16 queries), Jack Commer, Supreme Commander (just 1), and Nonprofit Ladies (6) as standalone efforts to agents and eBook publishers. I had no idea how to market a trilogy; I had only a vague concept of how publishing one, out of order, might get the others accepted. I also sent the 2009-revised The University of Mars five times, but overall I was concentrating on The Martian Marauders, refurbished in late 2009 and geared towards eBooks.

Many of the eBook publishers were starting to use online query methods and forms, speeding up the process considerably. No more waiting two months for a rejection; just get onto the next venue. And I had new confidence with putting The First Twenty Steps on PubIt. I mentioned this in my March 5, 2011 submission packet to Deron Douglas of the Canadian publisher Double Dragon Publishing for my seventeenth submission of The Martian Marauders:

A week later I was working at the second-floor Reference Desk at McKinney Public Library; at 5:30 Monday afternoon I opened my email.

What sort of sorcery was this? I hadn’t seen anything like this since 1976 when Pigiron Magazine accepted my story “Space, Time and Tania.” I was floored, immediately emailing back my overjoyed acceptance. Deron’s previous rejection of The University of Mars in 2010 had made me realize its 2009 reboot was not working, and I respected him for seeing that The Martian Marauders in contrast was publishable. He later indicated that other novels in DDP authors’ series would be accepted if they were of high quality, so within a couple months, at a time when I was also working on the first draft of a fourth Jack Commer novel, I secured contracts for Jack Commer, Supreme Commander, and Nonprofit Ladies.

The Martian Marauders publication was set for January 2012. It’s karmically interesting that McKinney Public’s second-floor Nonfiction Desk was the point of the Nonprofit Ladies vulgarity realization in 2006, and then, second-floor Reference the start of a new publishing mindset.

I later made other queries to publishers: The Soul Institute later in 2011, Akard Drearstone in 2012; Ethernet published “The Roadblock” in 2013 and Class Acts Books published my novel CommWealth in 2015. And Double Dragon published the first six novels of the Jack Commer Series, all with Deron’s excellent covers. As time went on I gravitated more and more to self-publishing, but that’s material for the next Writing Biography.

Why did it take me so long, from 1976 and “Space, Time, and Tania,” to succeed at publishing? For decades I castigated myself for my writing flaws and my so-called lack of ambition. Yet all the while I was living, gathering experiences, and experimenting.

And now life energies dramatically shifted.

copyright 2024 by Michael D. Smith